William John PALMER

Eyes brown, Hair dark brown, Complexion sallow

Fighting “Pedlar” Palmer – Bill’s Story

Can you help us identify Bill?

Bill was killed in Action at Fromelles. As part of the 32nd Battalion he was positioned near where the Germans collected soldiers who were later buried at Pheasant Wood. There is a chance he might be identified, but we need help.

In 2008 a mass grave was found at Fromelles, a grave the Germans dug for 250 (Australian) bodies they recovered after the battle. As of 2024, 180 of these soldiers have been able to be identified via DNA testing. We are still searching for suitable family DNA donors for Bill.

If you know anything of contacts for Bill here in Australia or his relatives from England, please contact the Fromelles Association.

See the DNA box at the end of the story for what we do know about his family.

Family - Pioneers of South Australia

The Palmers were early settlers in South Australia. Bill Palmer’s grandfather Henry Palmer was from the Reedbeds, South Australia, an area of seasonal freshwater wetlands to the west of Adelaide, where explorer Charles Sturt was one of the early settlers.

William (Bill) John Palmer was born in Port Pirie, South Australia on 15 September 1884, the fourth of Henry and Sarah Jane’s (nee Stoneham) ten children:

- Henry (1878-1950)

- Ethel May (1882- )

- Edith Maud (1883-1963)

- William John (1884-1916)

- Myrtle (1886-1974)

- Lily May (1891-1932)

- Leonard John (1895-1957) AIF No. 1963

- Muriel Amy Valetta (1897-1964)

- Esma Helen (1903-1995)

- Thomas Frederick Roy (1906-1934)

They lived in the nearby farming community of Crystal Brook in the state’s mid north. Bill did his schooling at the Port Pirie Public School and was working as a labourer when he enlisted. The family were active members of the local community - a newspaper article describing Bill’s father Henry in the newspaper for winning a prize for his poultry at the Crystal Brook show in 1911.

Off to War

Like so many other young men of the time, Bill may have been drawn to join the Army for a great adventure, to serve his country, or to escape the effects of high unemployment and the recent drought of 1914. Either way, Bill enlisted, signing on the dotted line at Keswick Barracks in Adelaide on 12 July 1915. At 30 years old and at 5’8” and 177 pounds, slightly bigger than most of the other men who were joining up (he is a well-built bloke for 1915), after a few months of military training he would surely be a formidable member of the Australian Imperial Force. Bill was assigned to the 32nd Battalion, B Company, one of the brand-new infantry battalions being assembled in Australia.

He marched into the Mitcham Army Camp on 16 August 1915.

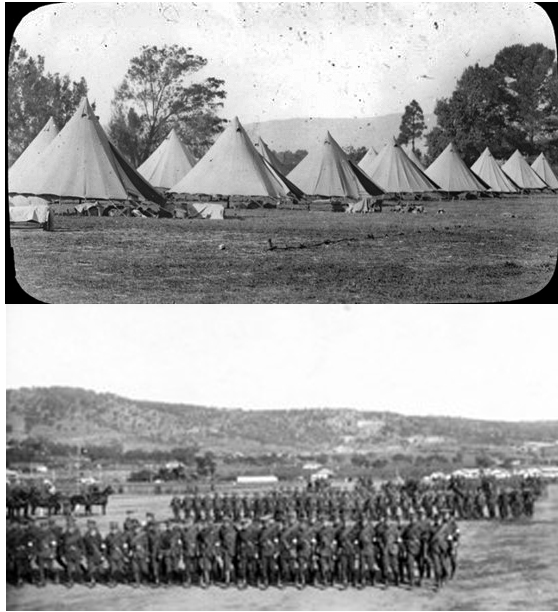

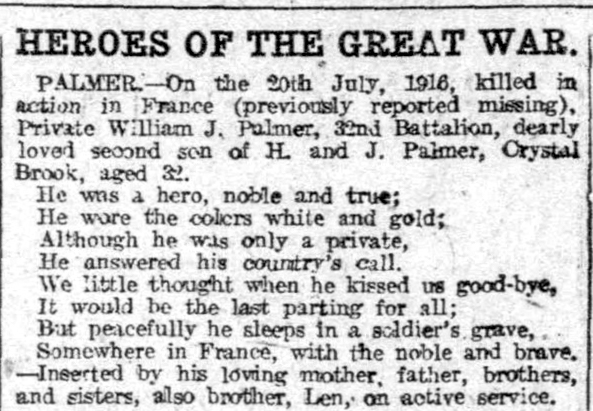

The 32nd was a composite battalion - some 500 recruits from South Australia were formed into the A and B companies and from across the other side of the country at Blackboy Hill near Perth, Western Australia, another similar sized bunch of keen young men were training to form the other half of the battalion, making up the C and D companies. The WA men joined the battalion in South Australia a few months later. At its peak, Mitcham Camp contained 4426 men and was the second largest town in South Australia. They lived in 10-man bell tents together and learned basic soldier skills such as physical training, bayonet fighting, rifle handling, bomb throwing and trench digging.

Bill did have a minor AWOL infraction, but as his family would later have moved from Crystal Brook to “East Marden” on Marden Road at Payneham, it is possible that he was visiting them at the family’s Adelaide home (or perhaps had a girlfriend). Bill’s mates now call him “Pedlar” (perhaps after “Pedlar Palmer”, an English boxing world champion of the time), and together they are now forming the critical bonds of mateship that will last a lifetime and hold them together on the field of battle.

After a month at Mitcham, the 32nd Battalion moved to Cheltenham Racecourse in mid-September to continue their training. A couple of weeks later they are joined by the Western Australian lads - now a complete battalion, training for war.

Training continued until the battalion departed for Egypt on 18 November 1915. They were split between two troop ships, HMAT A2 Geelong and HMAT A13 Katuna. Bill was on the Geelong, and excitement fills the air as they receive a magnificent send-off. The wharf is crammed with family, friends and well-wishers throwing coloured streamers which drape from the ship down onto the wharf and a band plays Auld Lang Syne as the soldiers embark.

As reported in The Adelaide Register:

“The 32nd Battalion went away with the determination to uphold the newborn prestige of Australian troops, and they were accorded a farewell which reflected the assurance of South Australians that that resolve would be realized.”

Many of the men would never have left their own state or town, so the journey at sea is the real beginning of the adventure. Their route carries them along the Great Australian Bight, then turning northeast around the tip of Western Australia. Seasickness is interspersed with army drills, sightings of albatross, flying fish and whales before reaching the hot, humid and calmer waters of the equator. Boxing matches are held in the evenings, and the men often sleep on the deck. After a month at sea the 32nd battalion lands at Suez.

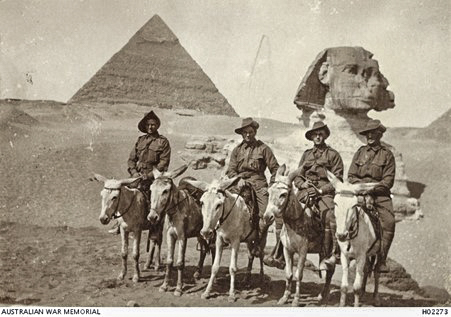

After landing, they spent four weeks at the El Ferdan outpost, several miles into the desert. Luckily for Bill, his platoon was assigned to Ridge Post, a smaller post a few miles south of El Ferdan and closer to the Suez Canal where they can bathe and fish while off duty. The battalion spent the next six months rotating through various outposts and at the major training camp at Tel-El-Kebir. The men are given leave on occasion and many take the opportunity to visit Cairo and the pyramids.

The 32nd Battalion’s stay in Egypt is relatively quiet; the Turkish do not mount any major attacks through the desert on the canal and their chief enemy is the stifling Egyptian sun and sand. George Bonney wrote at the time:

“We are in a deadly place now. Terribly hot and no water, only enough to keep you from thirst. If the Torrens River was here it would be worth its weight in gold. We get no face or clothes washed here….It’s a horrible place. All our water is carried by camels. You would be only too pleased to drink out of a horse trough, if you had the opportunity. Dirty water don’t stop us now. It’s worth more than tucker.”

Finally, the call to the Western Front comes and after a midnight train journey under the desert moonlight, the 32nd Battalion embarks onto the Transylvania on 17 June, bound for France. The luxury ocean liner which has been converted to a troopship changes direction every 5 minutes to avoid being torpedoed by German submarines and they land without incident at Marseilles on the 23rd. The men immediately board a train bound for the north of France. After six months of sun, sand and hardship in Egypt, the 3-day train ride from Marseilles to Armentieres through some of the most picturesque parts of Europe left a marked impression on the men.

As they disembark from the train on 25 June, they can hear the guns of the front booming ominously in the distance and the whole sky to the east is lit with searchlights and star shells as they march through the night to their camp. While Bill had been sweating it out in Egypt, his younger brother Len, a 20 year old carpenter, joined up in March 1916 and is assigned to the 50th Infantry Battalion (No. 1963).

Fromelles

Charles Bean wrote:

“…one of the bravest and hopeless assaults ever undertaken by the Australian Imperial Force…As was often the case with Australians, especially when first in action – could be felt straining like greyhounds on the leash and were not easily restrained from anticipating the word of command.”

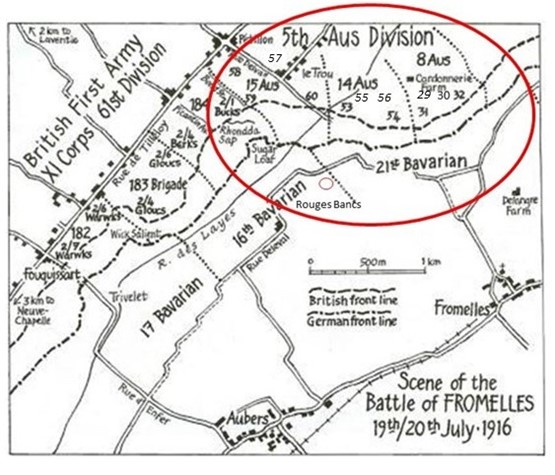

The troops have limited time to get used to life at the front, as a “stunt” is already brewing in which they will take part. The British General Staff decide that a diversionary attack to discourage German troops from moving south to reinforce at the Somme is needed, and they pick a section of the line located at Fromelles near the Belgian border. Bill’s Australian 5th Division has been deemed too inexperienced for use at the Somme and are chosen for the feint at Fromelles. The Germans easily spot the buildup and prepare their defenses.

The 32nd reaches the front line on 17 July, tired and with almost no experience of trench warfare. Nevertheless, the attack must go on and on the 19 July at 11 AM the British artillery opens up a fierce bombardment in an attempt to soften the German defences and cut the wire strewn across No Man’s Land. The German artillery responds, causing many casualties as the front line and as the support trenches are being packed with troops in readiness for the assault.

The men of the 32nd Battalion, who are on the extreme left flank, go “over the top” at 5.53 PM and they attempt to cross more than 100 meters of barbed wire and shell craters strewn across No Man’s Land. Bill Palmer and his mates of the 5th Platoon follow shortly thereafter at 6 PM and encounter a withering fusillade from the front and heavy enfilade fire from the left.

Sgt John Kennedy, D Company wrote:

”Then came the command ‘fix bayonets’ , and away over the parapet we started, and if ever there were such things as heroes, these men were, as not one flinched, but followed through the opening smiling, singing, and quite happy. Now came the sight, and it will live with me forever. The first sight I saw on ascending, was seeing the man in front of me blown to atoms, and then on the ground, hundred of my mates dead and wounded. They were in all positions, and piled in heaps, for you will understand that it was at this opening the Huns directed their chief fire.”

Bill ascends to the top of the parapet with his mates, disappearing into the maelstrom.

The Australians carry on the assault, taking the German front lines. They fight bravely and desperately for the remainder of the night to hold their newly won territory, but multiple German counter attacks finally force the Australian survivors to make a desperate charge back to safety through encircling German forces in the early hours of 20 July:

“The enemy swarmed in and the retirement across No Mans’ Land resembled shambles, the enemy artillery and machine guns doing deadly damage.”

What was left of the 32nd had finally withdrawn by 7.30 AM on the 20th. The initial roll call count was devastating – 71 killed, 375 wounded and 219 missing, including Bill. The final impact was that 228 soldiers of the 32nd Battalion were killed or died from wounds sustained at the battle and, of this, 166 were unidentified. Lieutenant Sam Mills survived the battle. In his letters home, he recalls the bravery of the men:

“They came over the parapet like racehorses……… However, a man could ask nothing better, if he had to go, than to go in a charge like that, and they certainly did their job like heroes."

Aftermath

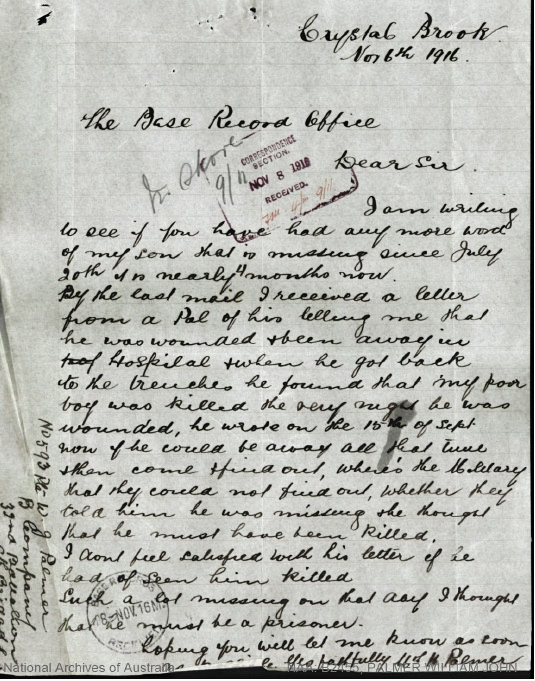

Word of the battle made its way back to Australia and Bill’s family, amongst thousands of others, wrote to official channels enquiring about their sons, but to no avail. They must wait to hear the fate of their son and brother. On 15 September they finally hear something - a mate of Bill’s wrote to the family advising that Bill had been killed. Bill’s mate, whose name is unknown, was wounded during the battle. No further news followed and Bill’s dad Henry, growing more and more frustrated, wrote again to military officials for confirmatory information if he was wounded, a prisoner or killed.

It is evident from the letters of Henry, his mother Sarah Jane and his sisters Myrtle and Lily that the family are holding onto hope that he may have been taken prisoner by the Germans. The chaos of the Western Front and the movement of men through the trenches, camps, hospitals of France, Belgium and England and the German prisoner of war camps makes tracking the fates of individual soldiers difficult.

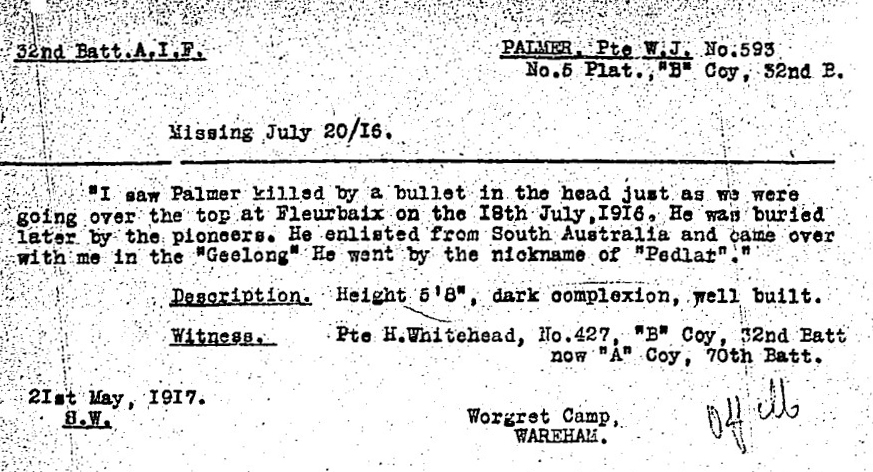

Sometimes it is not until a soldier is wounded or granted leave and taken out of the trenches that they are able to write letters home. Also, soldier witness statements are not always entirely accurate and are considered unofficial accounts until verified. At long last, in May 1917 the tireless Red Cross searchers discovered a witness to Bill’s death.

Private Herbert Whitehead (427), from Bill’s own company, who was in England, gave the following statement.

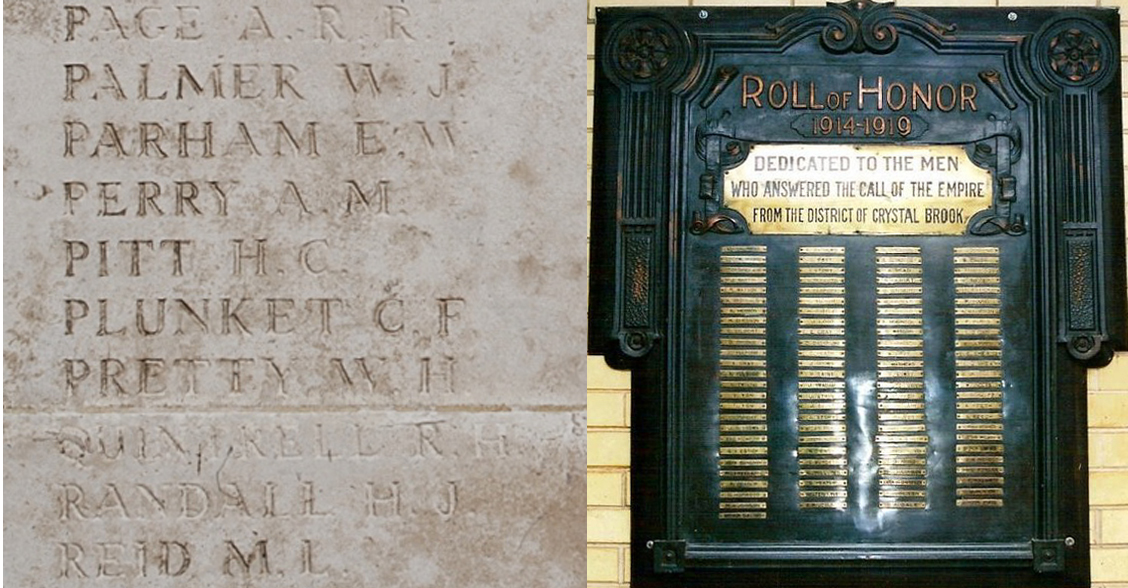

The family were not immediately made aware of this information, however. It was not until 12 August 1917 that the Army held a court of inquiry into Bill’s death – Bill was declared to have been killed at Fromelles on 20 July. The family are inally forced to accept the truth. They placed a family tribute in the local newspaper on 13 September 1917. In lieu of a funeral, it is the only way they know how to mark his passing. It had been over a year of constant worry for the family since the Battle of Fromelles.

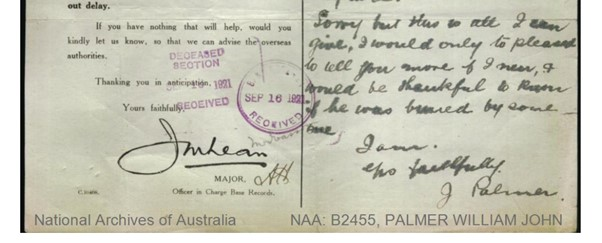

The family’s troubles are not over, however; an uneasy wait continues for Bill’s brother Len, still away in France with the 50th Infantry Battalion. Finally the war ends and Len comes home in 1919 and the family can have some sort of peace. Lingering worries about Bill’s final resting place remained. Was he given a proper burial as noted by Herbert Whitehead?

Perhaps the family can say their final goodbye in France now that the fighting is over, but they continue to hope for information after the war as to the whereabouts of his grave.

This is the last correspondence on record as to the fate of William Palmer. Like so many others that day, Bill had little chance of surviving the murderous fire on the left flank. He was hit by a bullet almost immediately, perhaps mercifully, in the head just as they were going over the top. Bill was awarded the 1914-15 Star Medal, the British War Medal, the Victory Medal and a Memorial Plaque and a Memorial Scroll.

He is commerated at:

- V.C. Corner Australian Cemetery Memorial in Fromelles, France (Panel 6),

- the Adelaide National War Memorial

- and the Crystal Brook District WW1 Roll of Honour.

Can Bill Ever be Found?

Was Bill actually buried by the 5th Australian Pioneer Battalion, per the witness statement? Was his grave marker destroyed by subsequent artillery, or was he mistaken for someone else? Was he collected by a German burial party and buried at Pheasant Wood pit among the 250 Australian soldiers they recovered?

As of 2024, 41 of the 167 unidentified soldiers from the 32nd have been found to be in the German mass grave at Pheasant Wood that was discovered in 2008. Identification has been able to be made from DNA matching from contributions from family members.

Bill may be one of the 70 yet unidentified soldiers of the 250 soldiers who were in the grave. We need to find family members to contribute DNA samples to find out if this was Bill’s final resting place from the battle to see if closure can finally be given to the family.

DNA samples are being sought for family connections to

| Soldier | William John Palmer (1884-1916) |

| Parents | Henry Palmer(1856-1937) Port Pirie SA and Sarah Jane Stoneham (1852-1939) Norwood, SA |

| Siblings | Henry (1878-1950) m Minnie Elizabeth Anthony | ||

| Ethel May (1882- unknown) | |||

| Edith Maud (1883-1963) m Francis J Donnelly | |||

| Myrtle (1886-1974) | |||

| Lily May (1891-1932) | |||

| Leonard John (1895-1957) AIF no. 1963 | |||

| Muriel Amy Valetta (1897-1964) m Henderson | |||

| Esma Helen (1903-1995) m Frederick H Arbon | |||

| Thomas Frederick Roy ( 1906-1934) |

| Grandparents | |||

| Paternal | Henry Palmer (1823- 1874) Reedbeds, SA and Eliza Abel | ||

| Maternal | William Stoneham (1821-1868) b Sussex and Barbara Gear Millar (1823-1887) b Sussex |

The Fromelles Association would love to hear from you

Contacts

(Contact: carla@fromelles.info or geoffrey@fromelles.info).

(Contact: army.uwc@defence.gov.au or phone 1800 019 090).

Donations

If you are able, please contribute to the upkeep of this resource.

(Contact: bill@fromelles.info ).