This photo was published under the name of Lieut. H. F. Briggs but identification has not been definitively confirmed.

Henry Francis BRIGGS

Eyes brown, Hair brown, Complexion fresh

Harry Briggs – He Took Things As They Came

Can You Help to Identify Harry?

Harry had led his Machine Gun Company to the forward trenches during the battle at Fromelles, but there are no records of his body being recovered or buried. There still is a chance he might be identified, but we need your help.

A mass grave was found in 2008 that the Germans had dug for 250 bodies they had recovered after the battle. 166 of these soldiers have been identified and given proper burials and recognition through finding family DNA donors. 80 soldiers remain and some identifications are highly likely. We just need to find DNA donors.

Harry did not have any family in Australia that we know of, but it is clear that he had strong ties to his family back in Brighton, Sussex, UK. If you know anything of Harry’s contacts here in Australia or his relatives in England, we would like to hear from you.

See the DNA box at the end of the story for what we do know about his family.

We have a second identification request in relation to the photo published in October 1916 (above) as we do not know for certain that it is “our” Harry Briggs. The name and timing of the “missing” report and the rank of Lieutenant match with our Harry’s story but the reference to Parramatta does not fit what we know of him. We cannot identify any other records of similarly named soldiers who it might be. Can you help confirm who is in this photo?

Background

Henry Francis Briggs (Harry), born on 25 February 1891 in Brighton, England, was the fourth of William and Florence (nee Hill) Briggs’ five children. His siblings were Florence, Edith (Ede), Frederick (Fred) and John. The family was obviously close, based on letters to his parents that he sent during the War. Typewritten extracts of these letters dated between March 1915 and July 1916 were obtained by the Australian War Memorial in 1928 and are a wonderful insight into Harry’s war service.

The Briggs lived in the Hanover area of Brighton where Harry’s father worked as a gas and hot water fitter. As he was growing up, Harry attended the Finsbury Road Board School, about half a mile from his home.

After his schooling, Harry did not follow his father into the building trade, as his brother Fred had done. Instead, he worked as salesman for a ‘gent’s outfitter’. He also showed an interest in the military and served in the Royal Field Artillery Territorial Force.

While it would seem he was quite well settled, at 21 he decided to head to Australia, departing the UK on 22 November 1912 and arriving in Sydney on 2 January 1913.

Similar to what he was doing in the UK, he found work as a salesman at Murdock’s Outfitters in Sydney.

Off to Fight for King and Country –to Gallipoli with the 3rd Battalion

Even though he had changed countries, his allegiances were strong and Harry was among the very first to enlist after War was declared. He enlisted as a private on 17 August 1914 and became a part of the first intake for the AIF’s newly formed 3rd Battalion. His regimental number was 63.

Training for the recruits was at several camps near the Randwick Racecourse area and it was both very basic – equipment issue, a lot of marching and some musketry practice - and very short. Two months after he had enlisted, Henry left Australia aboard HMAT A14 Euripides, headed for Egypt and arrived in Alexandria on 3 December 1914.

As planned, more extensive training continued at the Mena Camp outside Cairo. Reorganizations were also underway and Harry was assigned to the Machine Gun Section and on 22 January 1915 he headed to Abbassia for machine gun training.

In his letters home, Harry was obviously proud to be serving and of the quality of his newfound mates.

With now several months of training completed, they were headed to Gallipoli. On 5 April 1915, the 1060 soldiers of the 3rd Battalion boarded the Derfflinger. Harry had been proving himself capable with his move to the Machine Gunners and he was promoted to Corporal on 7 April.

They sailed to the island of Lemnos, arriving on 8 April and the next days were spent on boat drills, practising for the landing on the Gallipoli beaches. Orders to leave were received on 24 April with the 3rd Battalion to be in the second and third waves of the landing force.

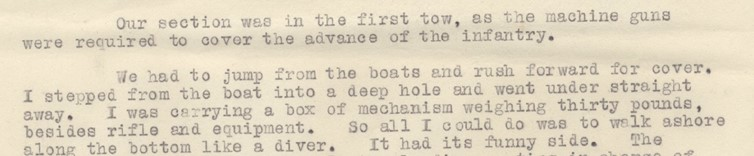

They arrived on 25 April at 4.00 am, began disembarking 5.30 am under heavy fire, and were ashore by 8.30 am. As part of the Machine Gunners, Harry described his landing experience as a bit more ‘complicated’ than the typical infantryman:

“I stepped from the boat into a deep hole and went under straight away. I was carrying a box of mechanism weighing thirty pounds, besides rifle and equipment. So all I could do was to walk ashore along the bottom like a diver.”

Harry’s positive attitude, given the absurdity of his situation, was also starting to be seen as he added, “It had its funny side.”

The Australians took the second ridge shortly after landing. However, according to the 3rd Battalion War Diaries [AWM], altogether the day’s battle was in favour of the Allies but the preliminary tally for the 3rd Battalion was “90 wounded, 20 killed, missing was impossible to calculate”. The battle raged on for the next two days “but the men hung out bravely and again showed their superiority of fire and discipline” and “we kept the enemy at bay despite the fact that we had been so insidiously shelled”. At midnight on the 28/29th they were relieved. “Our men were completely exhausted having been 4 days and 4 nights under the strain of a fierce battle.”

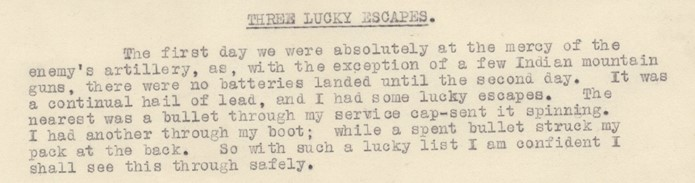

With all the confusion of the landing and ensuing battle, Harry’s family had been advised that he had been killed, but he found out about this and quickly sent a cable home that he had made it through. While he was OK, his “Three Lucky Escapes” as described to his father well and truly describe what a touch-and-go situation all the soldiers were in.

Having a cool head in stressful situations must have been noticed and Harry was promoted to Sergeant on 18 May 1915. The 3rd Battalion remained in the area, rotating in and out of the front lines until early August. They continued to lose both officers and gunners and Harry was put in charge of his unit for more than a month.

The next major action for the 3rd Battalion was the attack on Lone Pine in early August.

At 2.00 pm on 6 August 1915, they moved to their rendezvous point, with the 4th Battalion on their left and the 2nd on their right. At 5.30 pm, they rushed straight on and into the Turk’s trenches. After only an hour the Australians had captured the Turkish positions but suffered very heavy casualties.

Heavy counter attacks from the Turks began at 5.30 the next morning. The Australians had captured two Turkish machine guns and were able to use one of them against the Turks. Harry wrote home on 6 September 1915:

“You would have laughed when we first opened fire with it. At the first burst of lead there was absolute silence from Enemies lines for about 5 minutes, when they suddenly discovered they were receiving a dose of their own medicine.”

The trenches that were taken were filled with hundreds of dead bodies and the stench was awful. It took until 12 August to remove 137 bodies. Even with this fierce battle and the horrible aftermath Harry’s positive attitude shone through, “… why turn Grey over it.”

Eventually on 14 September 1915, the 222 men that were left in the Battalion departed for Lemnos for a well-earned rest. They stayed until the end of October and then returned to Anzac Cove but there was no further major action.

In the middle of November, Harry became ill and had to be sent to Heliopolis for treatment. The Battalion left Gallipoli on 21 December, returning to Egypt just after Christmas. Harry was able to rejoin his unit on 30 December 1915 at Tel-el-Kebir.

The Western Front with the 14th Australian Machine Gun Company

Major reorganisations were underway in Egypt to accommodate the heavy losses from Gallipoli and to integrate the large number of new recruits coming in from Australia. Harry was initially reassigned to the newly formed 55th Battalion on 13 February 1916, but recognizing his Gallipoli experience, he was sent to the 14th Australian Machine Gun Company on 11 March 1916.

On 12 March he was promoted to 2nd Lieutenant, no doubt in recognition of the personal strengths and leadership he demonstrated in Gallipoli.

Harry spent April in officer training in Ferry Post and additional machine gun training and Zeitoun. Preparations for the Western Front continued for all of the new units.

The 14th Machine Gun Company left Egypt in two groups. Harry’s group departed on 19 June 1916 on HMT Canada and arrived in Marseille on the 25th. They then boarded trains for a more than 60-hour ride to Thiennes, 30 kilometres from Fromelles. It was noted that their “reputation had evidently preceded them” as they were well received by the French at the towns all along the route.

By 10 July they were in into billets at Sailly, just behind the lines. While he knew the battle was looming, Harry kept his positive outlook, but he seemed to be in a contemplative mood when he wrote home on 12 July, just a week before the battle.

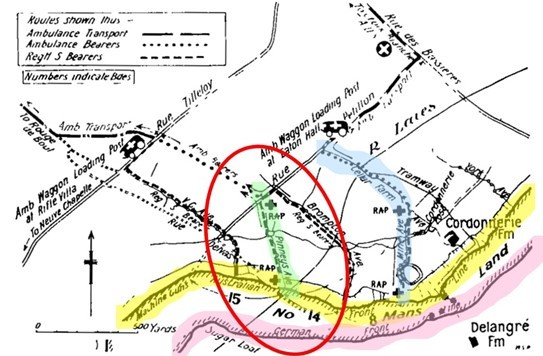

On 16 July they moved into position near Pinney’s Avenue. This was a particularly difficult location as there was a formidable German machine gun emplacement on the nearby Sugar Loaf salient. An attack was planned for the 17th, but it was postponed due to the weather.

All night on the 18th, bombardment was severe by both the British Expeditionary Force and the Germans, readying for an attack on the 19th.

Four waves of infantry began going forward at 5.43 pm on 19 July and they were to be followed by ten machine guns from the 14th Machine Gun Company. The first waves did not immediately charge from the Australian line, but went out into No-Man’s-Land and laid down, waiting for the British bombardment to lift.

At 6.00 pm, the Germans were rushed, their front line captured and the Australians headed for the second line under heavy fire.

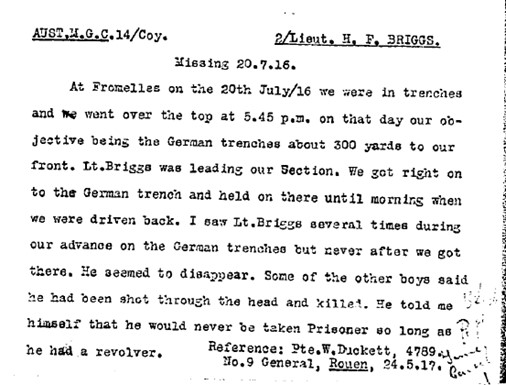

As reported by Private William Duckett (4789), Harry had been leading his unit in the advance on the German trenches when he was shot in the head and killed. Harry had also told Private Duckett:

“that he would never be taken prisoner as long as he had a revolver.”

There was another report from Private Harold Baker (5340) who stated that he saw Harry fall in No-Man’s-Land and that two men had told him that they had carried Harry back to the Australian trenches, but they were not sure if he was dead or alive.

The battle continued through the night, and while there had been significant advances, by the morning of the 20th the Australians were forced to retreat to their lines.

Harry was reported as “Missing in Action”.

No News for Harry’s Family

The family were advised he was missing but, unsurprisingly, no further detail was available.

With no information from the Army, Harry’s father contacted the Red Cross in January and in early May 1917 asking for information and whether he might have been taken prisoner or not. They were dismayed that there was no communication, particularly as they noted that Harry had been a regular writer.

The Red Cross expressed their sympathy but had little to offer. A reply in early May even advised that there was one unofficial report from a soldier that said Harry was in the 2nd Auxiliary Hospital in Southall, but the overall message from the Red Cross was that:

“it is so long after he disappeared that we very much fear he must have been killed.”

It was not until 26 Sept 1917 that a Court of Enquiry in the Field declared Harry as “Killed in Action”. His body has never been found.

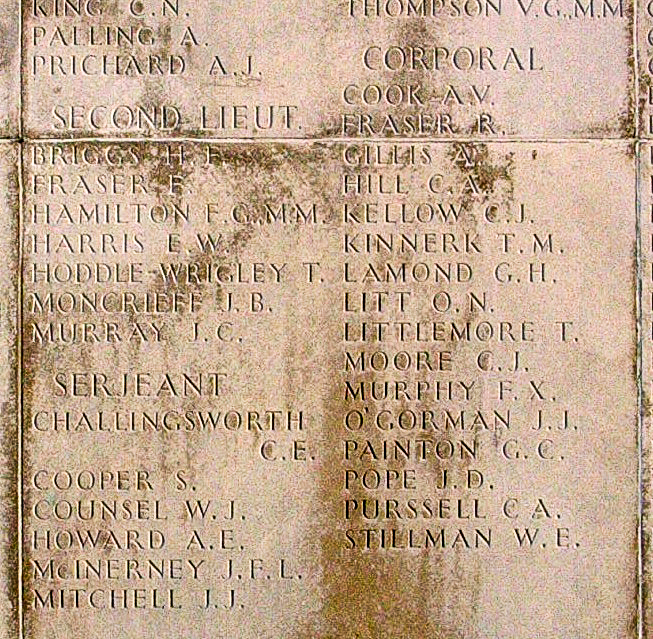

Harry was awarded the 1914-15 Star, the British War Medal, the Victory Medal, a Memorial Scroll and a Memorial Plaque. His name was commemorated on:

- Australian War Memorial, Canberra, Panel number 177;

- Australian National Memorial, Villers-Bretonneux, France and now moved to

- Panel 23, V.C. Corner Australian Cemetery and Memorial, Fromelles, France

The War was not yet done with the Briggs family, however. They also lost their son Fred, who was with the Queen's (Royal West Surrey) Regiment, 6th Battalion, regimental number G/69273. He died of wounds on 18 August 1918 leaving a wife and two children. Fred is buried in Daours Communal Cemetery, France.

The youngest son, John Charles Briggs, also served during the war as a driver in France from December 1914 with the Army Service Corps (service number 571). Fortunately, he survived the war and returned home to England in 1919.

Still Hope to Identify Harry?

As described at the start of this story, it is possible that Harry is one of the yet to be identified soldiers from the mass grave that was dug by the Germans and only discovered in 2008. We just need to find DNA donors.

If you know anything of Harry’s contacts in Australia or in England we would like to hear from you.

DNA samples are still being sought for family connections to

| Soldier | Henry Francis BRIGGS 1891-1916 |

| Siblings | Florence Mary 1883-1967 | ||

| Edith Emma 1884-1966 (m Herbert W. BRIGGS 1890-1969) | |||

| Frederick William 1889–1918 (m Mary F. BLUNDELL 1894-1980) | |||

| John Charles 1896-1990 (m Hilda STOTER) |

| Parents | William James BRIGGS 1858-1918 and Florence HILL 1858-1941 |

| Grandparents | |||

| Paternal | William BRIGGS 1809-1873 and Mary HARDS 1821-1886 | ||

| Maternal | Daniel HILL and Mary Ann HOLLGUTH |

The Fromelles Association would love to hear from you

Contacts

(Contact: carla@fromelles.info or geoffrey@fromelles.info).

(Contact: army.uwc@defence.gov.au or phone 1800 019 090).

Donations

If you are able, please contribute to the upkeep of this resource.

(Contact: bill@fromelles.info ).