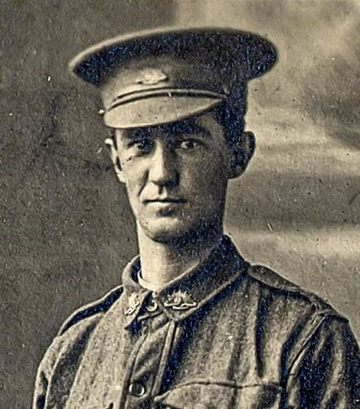

Raymond Hadden CHOAT

Eyes grey, Hair dark, Complexion medium

Three Choat Brothers - One Battle, Three Outcomes

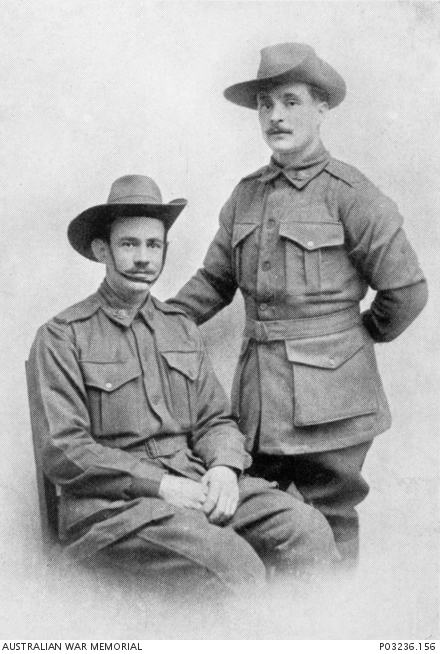

Joseph and Alice Mary (nee Broadbent) Choat and their seven sons lived in the southeast of Adelaide. The three eldest, Raymond, Wesley and Archibald all served in World War I. Raymond was born 22 March 1892, Wesley on 27 August 1895 and Archibald 7 June 1897. Four younger sons – Harley (Max), Henry, Mervyn and Ian - were born between 1899 and 1910.

Standing - Raymond, Wesley, Archibald

Sitting - Henry, Alice, Mervyn, Joseph, Ian, Harley

The family originally lived in semi-rural Cherry Gardens, but moved closer to downtown Adelaide when their older boys were quite young. The family’s new home was in Clarence Park and the boys attended the Goodwood Public School. After schooling, Raymond, the eldest, went on to pursue a course of study at Adelaide University for accountancy and a diploma of commerce. At the time of his enlistment, he was working in the Railway Controller's office.

In contrast, Wesley was determined to become a farmer and spent six years on the Yorke Peninsula. After he left school, Archibald was a labourer and his mother described him as “a born mechanic”.

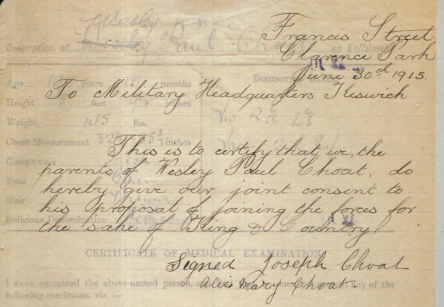

Signing Up

When the War began, the three eldest Choat sons were keen to sign up. Raymond was 23 years old, but Wesley was not yet 20 and Archibald only 18, so the two younger boys both needed parental approval. Joseph and Alice were fully supportive of their two underage boys joining up with Archie’s letter of consent (dated 30 June 1915) stating that they - “… do hereby give our joint consent to his proposal of joining the colors for the sake of King & Country.”

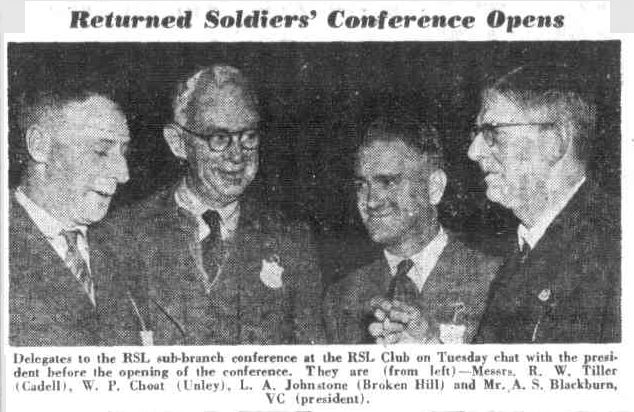

The brothers were all assigned to A Company in the 32nd Battalion which was just being formed in August 1915. A and B Companies were from South Australia while C and D from Western Australia. The men from WA arrived in Adelaide at the end of August and training for all continued there until they departed for Egypt on 18 November 1915 on the troop ship HMAT A2 Geelong. As reported in The Adelaide Register:

“The 32nd Battalion went away with the determination to uphold the newborn prestige of Australian troops, and they were accorded a farewell which reflected the assurance of South Australians that that resolve would be realized.”

The Choat boys also had five cousins who all served on the Western Front.

The 32nd arrived in Suez on 14 December 1915 and settled into El Ferdan, just before Christmas. They also marched to Ismalia, Tel El Kabir, Duntroon Plateau, Ferry Post and Moascar, continuing their training all along.

The Western Front – Straight into Battle

After six months in Egypt, the 32nd sailed to France to support the British Expeditionary Force on the Western Front. They left from Alexandria on the ship ‘Transylvania’ on 17th June 1916 and arrived at Marseilles, France on 23rd June 1916. After that, they departed Marseilles by train, for the two-day trip to Hazebrouck, about 30 kilometres from Fleurbaix.

Wesley, for one, was glad to be out of Egypt, but well aware of what laid ahead:

“The change of scenery in La Belle France was like healing ointment to our sunbaked faces and dust filled eyes. It seemed a veritable paradise, and it was hard to realise that in this land of seeming peace and picturesque beauty, one of the most fearful wars of all time was raging in the ruthless and devastating manner of "Hun" frightfulness”.

The troops then settled into Morbecque and training continued with a focus on bayonet training and the use of gas masks. D Company’s Lieutenant Sam Mills’ letters home were optimistic for the coming battle:

“We are not doing much work now, just enough to keep us fit—mostly route marching and helmet drill. We have our gas helmets and steel helmets, so we are prepared for anything. They are both very good, so a man is pretty safe.”

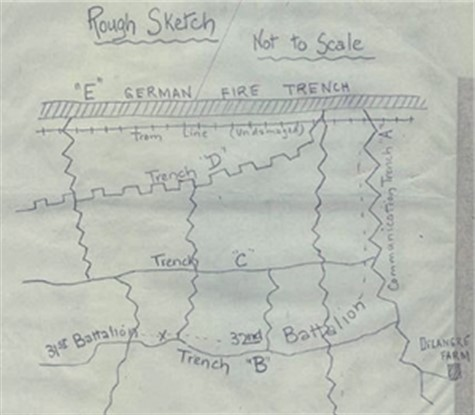

On 14 July, they moved into Fleurbaix and were into the trenches on 16 July, just one year after the Choat boys had enlisted. On the 17th they were reconnoitering the trenches and cutting passages through the wires, preparing for their attack, but had to be moved back to Fleurbaix due to bombardment of the trenches. In the morning of the 18th, A and C Companies went back into the trenches to relieve B and D Companies. B and D rejoined the next day and by 4.15 pm on the 19th they were readying for their attack. All were in position by 5.45 pm and the charges over the parapet began at 5.53 pm.

The three Choat brothers were in the first and second waves of the attack, forming the left side of the 32nd Battalion’s position. The 32nd was successful in their initial assaults, and by 6.30 pm they were in control of the German’s 1st line system, which was described as “practically a ditch with from 1 to 2 feet of mud and slush at the bottom”. However, by 8.30 pm their left flank was under heavy bombardment with high explosives and shrapnel. Return bombardment support was provided and the troops were told that “the trenches were to be held at all costs”.

Fighting continued through the night. At 4 am, the Germans began their attack from the Australian’s left flank and then on the front. A charge at the Germans’ firing line was made by the Australians, but they were low on grenades and there was machine gun fire from a machine gun from behind an emplacement at Delangre Farm. They were so far advanced that they were getting shelled by both sides!

By 7.30 am on the 20th, what was left of the 32nd had withdrawn. The toll on the battalion was devastating – 718 casualties, 90% of their effective strength.

Privates Raymond, Wesley and Archibald Choat were not with them.

Three Family Outcomes from One Battle

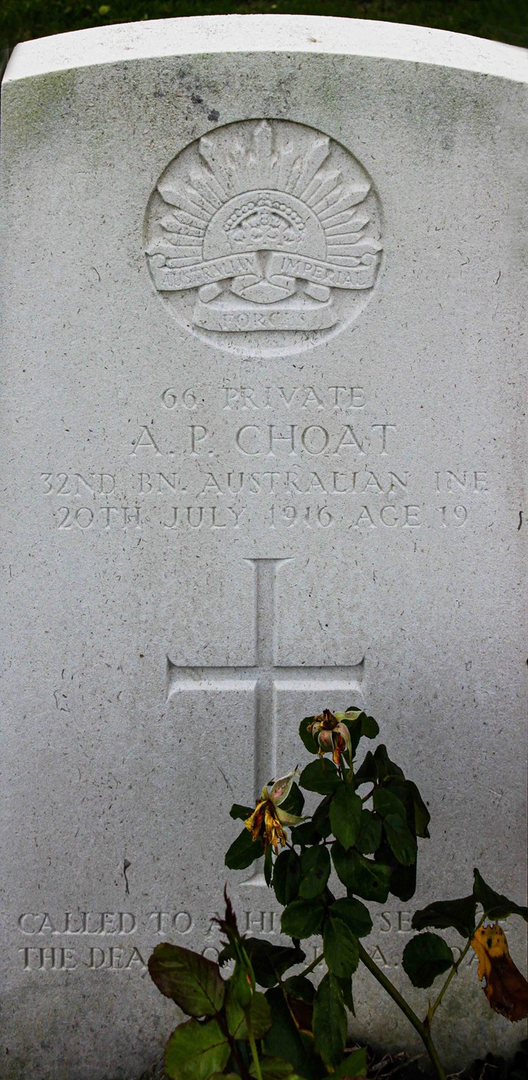

1. Killed in action – Archibald (Archie)

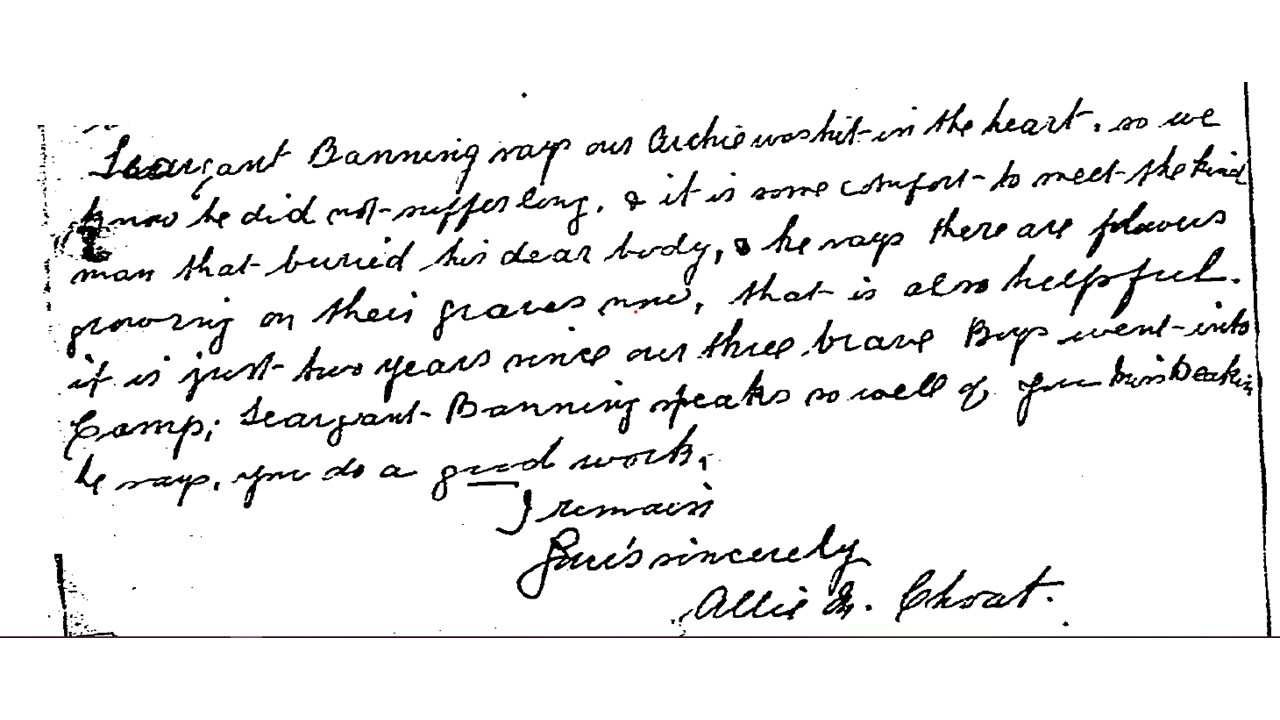

As detailed in a communication to the family by Sergeant Walter Banning, a 44-year-old career soldier originally from the UK, Archibald’s fate was clear. During the battle, 19-year-old Archibald was hit in the heart, a quick death.

Archie’s body was recovered and he was buried by the Australians near the field of battle in Rue Petillon Cemetery, Plot 1, Row L, Grave 47, Fromelles, France. The inscription includes:

“Called to a Higher Service

The Dear Son of A&J Choat”

In his obituary, Archie, who was just 19 years of age, was described as:

“of a bright, lovable disposition, and enjoyed the esteem of a wide circle of friends.”

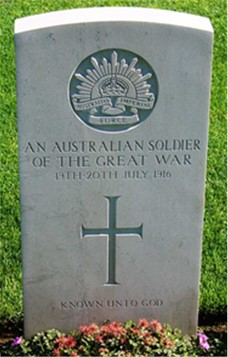

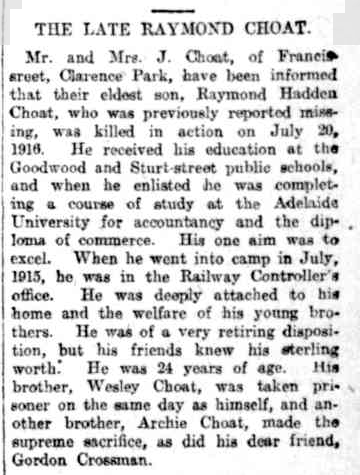

2. Missing in Action – Raymond (Ray)

Raymond’s fate was unknown. He was reported as being killed by a shell to the heart and buried nearby, but the initial details of his death in the Red Cross files would appear to have been mistaken for Archibald’s. There are no further records for Raymond and he remained “missing” with the family suffering the uncertainty of not knowing for more than a year.

On 12 August 1917, he was officially declared to have been killed in action by a Court of Inquiry in the Field but his place of burial was unknown. In 2008, a mass grave was discovered that had been dug by the Germans to bury soldiers from the battle. While there have been efforts by the Australian Defence Force and the Fromelles Association of Australia to identify missing solders by DNA testing, Raymond is not among those identified as of this time.

As noted in his obituary, Raymond’s one aim was to excel. He was also deeply attached to his home and the welfare of his young brothers. He was of a very retiring disposition, but his friends knew his sterling worth.

3. Wounded and taken as Prisoner of War – Wesley

Wesley was wounded in the battle and was captured. Fortunately, he survived and detailed his experiences in his memoir held by the Mitchell Library, (excerpts below) :

..we had some splendid shooting, took the first line, and dug ourselves in about a hundred yards beyond. The digging did not go very deep, as when at a foot in depth we found water, and we had to make a barricade.

Those of us who had reached so far held on, and made as much cover as possible, and were complimenting ourselves on a good success at the first advance, when the order came: "We are surrounded, every man for himself".

Although surprised, we formed up and tried to charge back to our own lines, but a piece of shrapnel, whether from friend or foe I could not say, was stopped by my nose, the force of which toppled me into a nearby shell-hole and robbed me of my senses for some time.

On coming to consciousness all was comparatively quiet, but 'Fritz' was around gathering up the living and then the awful realisation came over me "I am a prisoner of war". The thought alone was enough to try the strongest nerve, and by what I saw and had heard, I fully expected to be killed outright or worked to death behind the lines.

My feelings were made more miserable by the fact that I was the only man living in that sector, and began to think that 'my number' surely was up, but on getting into their communication trench I found, to my immense relief there were others of my comrades in the same plight, and on reaching the road to which this trench led, I met more of our boys, about twenty in all. We were then marched to the Field Dressing Station, where the worst of the wounds were dressed, and any case of men unable to walk, they were sent direct to hospital.

On reaching this [dressing] station I found three hundred in all, 'Tommies' and 'Aussies'. From there we were placed under a mounted guard and taken right through Lille, where we were greeted at almost every window by a camera, anxious to get a good photo of the first batch of 'Aussies'. The sight of us, battle worn, muddy and with clots of blood all over us, had a very depressing effect on the French population, and it was a very frequent and pathetic sight to see an elderly woman dressed in black, sobbing and crying over our apparent failure.

Another very common experience was when some French lady, who was probably depriving herself and family of needed food, would venture as close as possible, and attempt to hand us some piece of their black war bread. But as soon as a sentry noticed, he would turn his horse in her direction, flourishing his lance, and using very lurid language.”

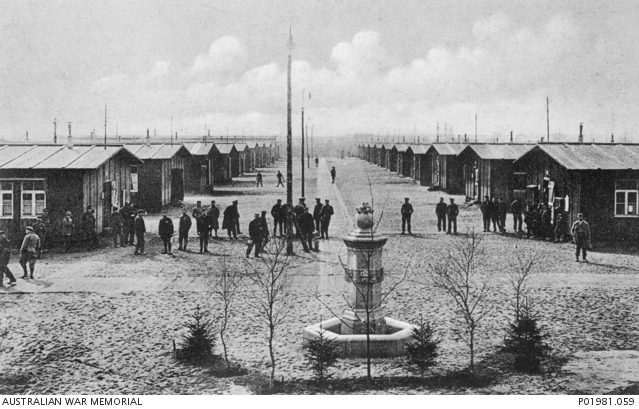

Wesley was kept in the civilian prison of Lille for two days while the Germans rounded up a total of 500 soldiers — the number required to fill the prisoners-of-war train bound for the Dulmen camp, located about 40 kilometres from the Dutch border. This was just one of eight prison camps where Wesley was imprisoned.

Wesley spent nine months planning to escape. Luckily during this time, one of his guards had taught him enough German to, hopefully, carry him through.

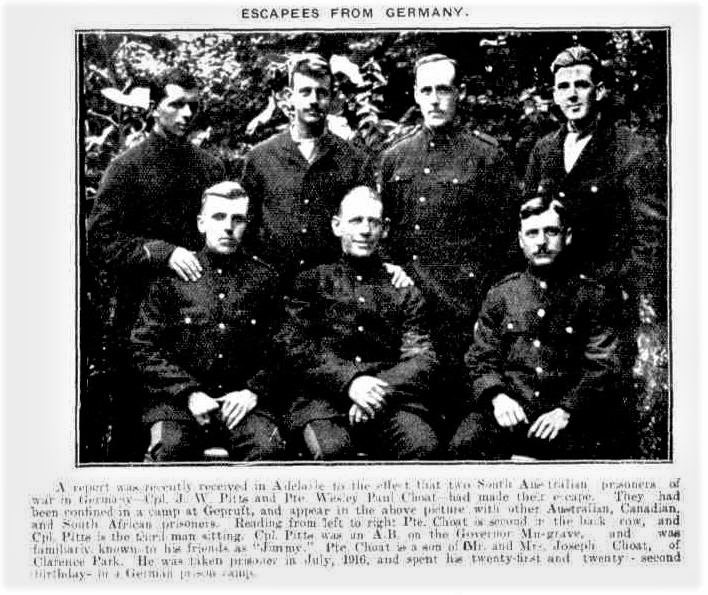

In September 1917, Wesley, with a fellow Australian and a Canadian soldier broke out. Posing as Belgian workmen, the three escapees caught trains across Germany and avoided local police. They were caught, however, just five kilometres from the Netherlands border when a sentry demanded passports and a subsequent search led to the discovery of prison camp currency on them.

Back in camp, Wesley endured punishment of two weeks in solitary confinement, but he had the courage to try again.

In preparation, he bought a compass from a French prisoner for two shillings, a mate procured a descriptive map and railway timetable, and Wesley studied the stars to assist his navigation. Wesley and fellow South Australian James Pitts tailored their clothes to pass as Belgian workmen, with Wesley to carry on any conversation that might be necessary.

Just three months after Wesley’s first escape attempt, six men tried a second time on December 6, 1917, a cold and stormy night. The six men divided into pairs with the two South Australians scrambling south-west to Dusseldorf. Wesley and James almost walked straight into a German officer as Wesley described in his book:

"Our trouble was caused by a young Fritz trying to get through the protracted business of stating goodbye to his lady love and standing in the middle of our road”

The two escapees hid in a drainage ditch and waited for the young lovers to complete their farewells before they could continue on their way.

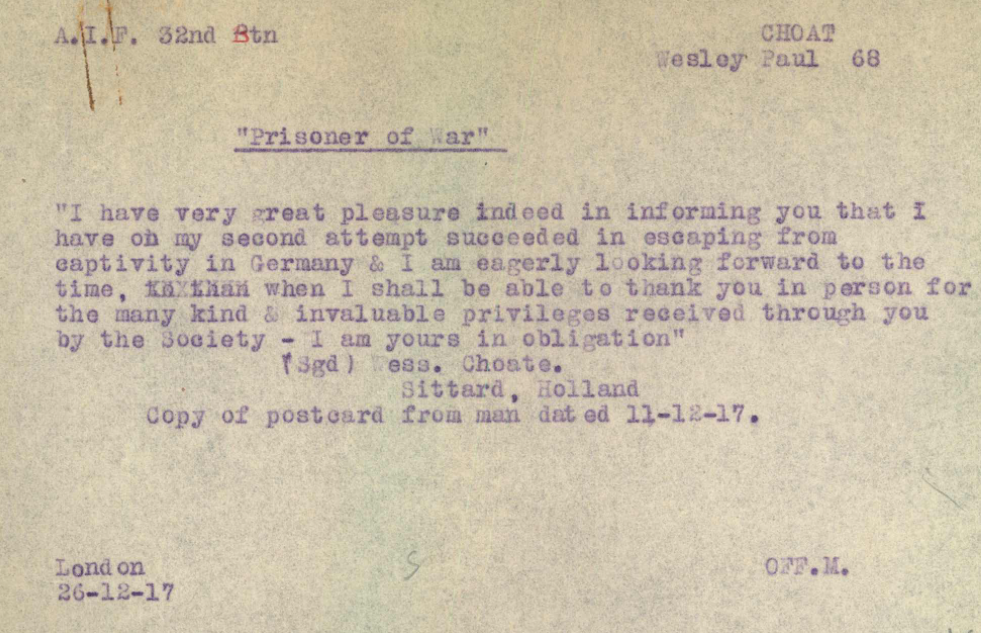

Approaching the border, Wesley and James walked through a lumberyard and snuck under what they believed to be a border sentry tower and, during a torrential downpour, crossed into the Netherlands. They found shelter with local Dutch families and soon sent notice of their escapades which were widely reported in the newspapers back home.

The men were then in Sittard, Netherlands for five weeks before travelling to stay in Sutton Veny, Wiltshire to continue their convalescence and debriefing.

A heartfelt letter by Wesley's mother Alice to authorities pleaded for the safekeeping of her only remaining serving son and it helped to secure his return home:

"Oh kind sir, if it be possible, I beseech you to allow our son….. to be put in some (safe) corner on home service in England, or anywhere, as long as he is safe, but Sir, I do implore you not to send him back to the Front…."

Wesley’s significant wartime efforts were supported by the AIF and he returned to Australia in May 1918. He was awarded the Military Medal on April 29, 1920 "in recognition of gallant conduct and determination displayed in escaping or attempting to escape from captivity".

Post-War – The Choat Family Still Upholding Strong Values

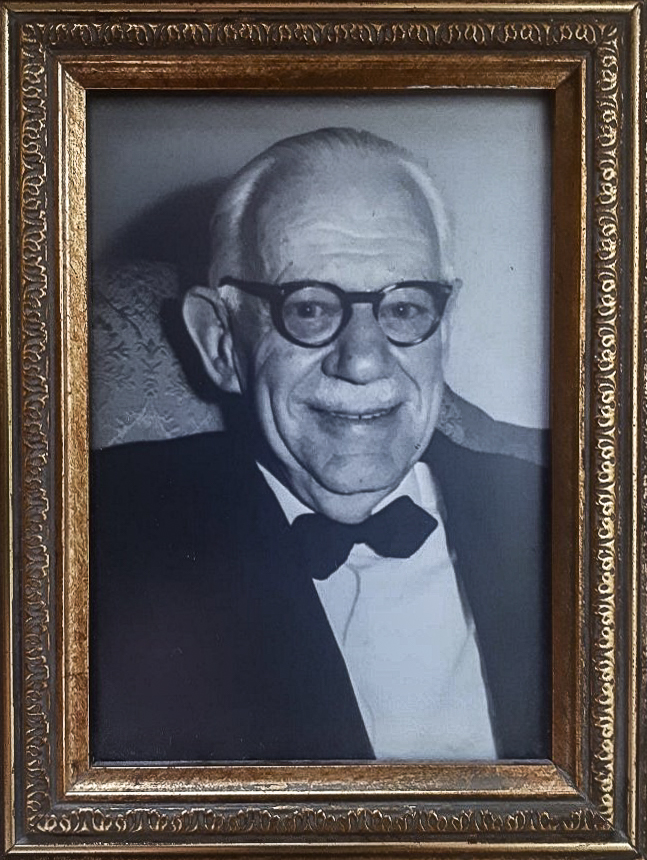

In July 1918, Wesley was involved in a campaign to speak to school children about the danger of feeling indifference to the war and to teach them the importance and nobility of self-denial and self-sacrifice. He was also a member of the Colonel Light Gardens RSL sub-branch from November 16, 1918 till December 31, 1975.

While Wesley wrote a personal memoir of his escape from Germany called, “A Bold Bid for Blighty” (which can be found in the Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales), like many veterans, Wesley kept much of his experiences to himself. His grandson, Ronald Sainsbury writes:

“My mother told me that 'Pop' as we called Wes, had been through hell in the war but I knew no detail. Mum told me that Wes had written a book and had tried unsuccessfully to get it published. Why it wasn't, I don't know and I had not read it at the time.

I did ask more than once how he managed to escape. All I was ever told was that he was so poorly nourished and thin that he escaped between the bars! At the time this explanation was hard to accept and I didn't ever really believe it.

When chatting with Pop as a young teenager we didn't discuss the war as there were other things more important at the time. He left a lasting impression, e.g. I thought of him when I decided to get married in '83 to my now wife. Pop said, 'the girl you marry should be the one you want to have your children'.

From Pop's perspective, he parked his war time experiences, at least from me. He was a keen member of the RSL, but I have no way of knowing if other former soldiers also parked their experiences or relived the horrors during discussion over cards, or only at night when trying to sleep.

He proudly marched every Anzac Day, and I recall Pop reflecting that each year there were less of his mates/marchers. I also recall a year Wes himself did not feel well enough to join his comrades - this must have been painful.”

Wesley died of natural causes on January 15, 1976, aged 81, and was buried at Centennial Park Cemetery.

The Choat family has truly given their all – indeed called to a higher service.

Finding Ray

DNA samples are being sought for family connections to

| Soldier | Raymond Hadden Choat (1892–1916) |

| Parents | Joseph Choat (1865–1933, Goodwood SA – South Australia) and Alice Mary Broadbent (1868–1946, Cherry Gardens SA – South Australia) |

| Siblings | Wesley Paul Choat (1895–1976) | |||

| Archibald Percy Choat (1897–1916) | ||||

| Harley Maxwell Choat (1899–1970) | ||||

| Henry Ambrose Choat (1904–1975) | ||||

| Harry Herbert Choat (1905–1975) | ||||

| Mervin Wilbur Choat (1909–1997) | ||||

| Ian Elwin Choat (1910–1976) |

| Grandparents | |||

| Paternal | Henry Choat (1828–1904, Little Sampford, Essex – Millswood SA) & Caroline Turner (1824–1904, England – South Australia) | ||

| Maternal | Elijah Broadbent (1831–1913, Derbyshire ENG – South Australia) & Caroline Field (1834–1872, Woodchurch Kent ENG – Cherry Gardens SA) |

Seeking DNA Donors

Contacts

(Contact: carla@fromelles.info or geoffrey@fromelles.info).

(Contact: army.uwc@defence.gov.au or phone 1800 019 090).

Donations

If you are able, please contribute to the upkeep of this resource.

(Contact: bill@fromelles.info ).