Frederick HULKS

Eyes unknown, Hair unknown, Complexion unknown

Frederick Hulks – A loyal soldier, father and son.

Can you help us identify Frederick?

Frederick was a highly regarded professional soldier, a father of four, and a man with nearly two decades of military service before he joined the AIF in 1915. He was killed at the Battle of Fromelles on 19 July 1916. His body was never recovered, and he remains one of the many Australian soldiers with no known grave.

Jessie, his widow, spent months searching for answers. Despite witness statements confirming his death, the confusion over his status and burial meant she never had certainty.

We are seeking DNA connections or descendant information that might help identify Frederick if he lies among the unnamed soldiers buried at Pheasant Wood.

If you are related to Frederick, or to his parents or siblings, please contact us.

Early Life

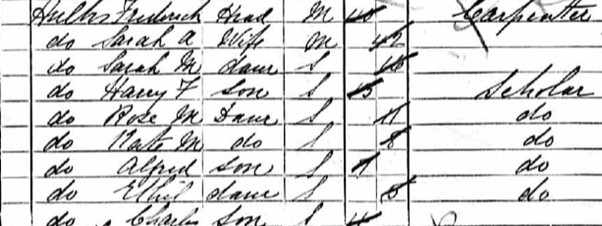

Frederick was born on 22 December 1877 in Chelsea, a district of London. He was the eldest child of Frederick Joseph Hulks and Sarah Ann Cannell. His father worked as a carpenter and joiner, a trade common in the skilled working class of Victorian England. Fred senior came from Hertfordshire and wife Sarah from Marylebone, London. Frederick grew up in a large and close-knit family. Census records show the family living in St Pancras in 1881 and later in Tottenham, north London, by 1891. In both 1881 and 1891 census, To his family, Frederick was known as Harry.

He was one of seven siblings:

- Sarah Margaret Hulks (1875–1931) m 1927 Fred Bull

- Frederick (1877-1916) Fromelles

- Rose Mary Hulks (1879–1925)m 1914 Fred Bull

- Kate Maud Hulks (1882–1937) m David Alexander

- Alfred Hulks (1883–1914) Canada

- Ethel Hulks (1885–1968)

- Charles Hulks (1887–1930)

In 1891, Frederick Senior was the sole breadwinner for the family, working as a carpenter. Tragedy struck in 1894 when he died suddenly, leaving behind his wife Sarah and their children. His son Frederick was just 16 at the time, and Sarah now faced the daunting task of supporting the younger children alone. The family’s sudden loss plunged them into financial and emotional crisis. With few options available, heartbreaking decisions had to be made.

The two youngest boys, only 8 and 12 years old, were placed into care and eventually sent to Canada under the British child migration scheme — a forced separation that marked a permanent turning point for the family:

“Some 80,000 British children - many of them under the age of ten - were shipped from Britain to Canada by Poor Law authorities and voluntary bodies during the 50 years following Confederation in 1867.”

Alfred eventually received a homestead grant in Alberta in 1904 and remained there until his death in 1914. Charles was recorded in the 1901 Canadian census as a 14-year-old farm labourer in Ontario. His life took a tragic turn when he died by suicide in Port Hope, Ontario, in 1930. At the time, he was working as a 2nd class marine engineer with the Mathews Steamship Company and had no known surviving family.

Meanwhile, back in England, the 1901 UK Census shows Sarah working as a self-employed monthly nurse. Her daughters Sarah, Kate, and Ethel were making shirt ties from home, and Rose was employed by a florist. It is likely that Frederick—the eldest surviving son—was also contributing to the household income, although by then he was already serving abroad.

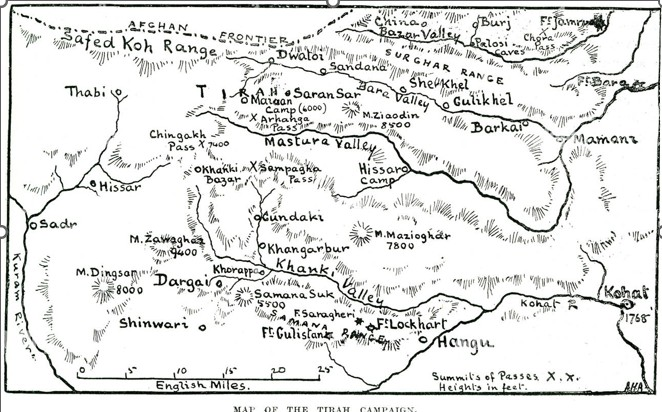

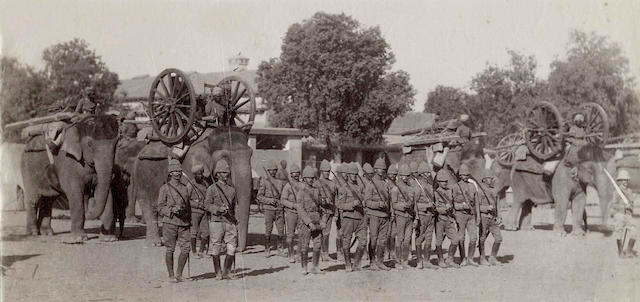

At 18, Frederick enlisted on 22 January 1896 with the 2nd Battalion, Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry (DCLI), one of the British Army’s historic regiments. His service took him across the Empire—India, Ceylon, South Africa, and finally to Hong Kong—during a period marked by colonial conflicts and imperial expansion. This included the Tirah Campaign (1897–1898) and Punjab frontier duty on the North-West Frontier of India, a volatile border region where British and colonial forces were regularly engaged in conflicts with Pashtun tribes.

The Second Boer War (1899–1902) in South Africa, where Frederick served in the mounted infantry or light infantry roles typical of the DCLI.

His rise to Company Sergeant Major — the most senior non-commissioned officer rank — suggests he was highly regarded for his discipline, leadership, and experience. During his time in South Africa, Frederick met and married English girl Jessie Christina Wells on 1 January 1906 in Wynberg, Cape Province (now part of Cape Town). Sometime between 1906 and 1911, Frederick and Jessie relocated to the UK. The 1911 English Census records them living in Bodmin, Cornwall, near the DCLI depot, where Frederick likely continued serving as an instructor or depot staff member.

After 19 years of continuous military service, Frederick was honourably discharged at his own request on 1 February 1914 in Hong Kong. His discharge papers record his special qualifications, he had been in charge of the Pioneers’ Shop for three and a half years, working as a carpenter—a skill that likely provided a steady contribution to the regiment’s logistical and engineering needs. By the time of his discharge, his stated residence was Mitchell Street, Putney, Parramatta, New South Wales, confirming that he and Jessie had chosen to settle in Australia following his long service abroad.

Source: Army Discharge Record – Ancestry.com.au, https//www.ancestry.com.au/imageviewer/collections/1114/images/miuk1914a_084969-00332?pId=490145

Frederick and Jessie eventually settled in Woollahra, a leafy suburb in Sydney, New South Wales. He and his wife Jessie established their family home on Ocean Street, naming it “Welby.” Drawing on the carpentry skills honed during his time in the British Army, Frederick found employment as a piano maker—a highly skilled trade that allowed him to support his growing family.

Frederick and Jessie had four children:

- Doris Jessie Christina Hulks (1911–1975)

- Ivy Hulks (1913–1913)

- Phyllis Irene Hulks (1915–2007)

- Frederick Alfred Hulks (1916–2014)

In addition to his civilian trade, Frederick continued his connection to military life by joining the Instructional Staff of the New South Wales military forces. There, he trained young recruits in drill, marksmanship, and military discipline, passing on the expertise gained through nearly two decades of service with the British Army.

Off to War

When war broke out in 1914, Frederick was already in his late 30s and a seasoned soldier. On 1 September 1915, at the age of 37, he enlisted in the Australian Imperial Force and was commissioned as a Lieutenant in the newly formed 32nd Battalion. With nearly two decades of prior service in the Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry and more recent experience as a drill instructor with the New South Wales Instructional Staff, Frederick was exceptionally well-qualified to lead and train new recruits.

The 32nd was a composite battalion raised in both South Australia and Western Australia, with training camps established at Mitcham and Blackboy Hill. Frederick’s deep military knowledge made him an ideal officer to help shape the battalion in its early months. Although his service records list him as part of B Company, contemporary Red Cross witness accounts and internal battalion evidence indicate that he was serving with D Company by the time of the battalion’s first major engagement.

Frederick embarked with the 32nd Battalion from Adelaide on 24 November 1915 aboard HMAT Katuna. The battalion’s embarkation was split between Katuna and Geelong, and while his name appears on the Katuna nominal roll, some sources suggest he may have later transferred from or to Geelong when the transports regrouped in Egypt.

The unit arrived at Suez on 18 December 1915, continuing on to Tel el Kebir and later Ismailia, where they trained under harsh desert conditions. Frederick played a leading role in instructing men in bayonet fighting, musketry, field manoeuvres, and trench warfare — vital skills for the brutal conditions of the Western Front.

By June 1916, the battalion was deemed ready for combat. They sailed from Alexandria aboard the Transylvania on 17 June and arrived in Marseilles on 23 June. From there, they crossed France by crowded troop trains to the Armentières sector, an area nicknamed “the nursery” and thought to be a quieter part of the front. But in reality, the trenches near Fleurbaix were cold, wet, and under constant threat from German snipers and artillery. The men quickly learned that even so-called “quiet sectors” were anything but safe.

Within weeks, they were ordered into battle. Their objective: to assault the German lines near the village of Fromelles. Intended as a diversion for the Somme offensive further south, the attack was hastily planned and criticised by senior officers. Many feared that sending inexperienced units into a frontal assault against well-prepared German positions would be a disaster.

Nevertheless, Frederick and his men stood ready to face the ordeal. On 19 July 1916, they would take part in what would become one of the most tragic and costly battles in Australia’s military history.

The Battle of Fromelles

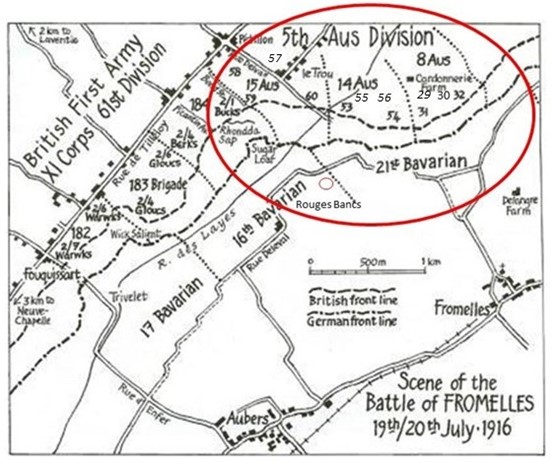

Frederick had been in France for only a few weeks when the order came. The newly arrived 5th Division was to make its debut in a large-scale assault on German lines near the village of Fromelles. Officially, it was a diversion — intended to draw German forces away from the Somme offensive further south.

The 32nd had taken up position in trenches near Fleurbaix on 16 July 1916. Over the following days, they prepared for the attack, laying down boards, cutting through barbed wire, and practicing their assault routes. Frederick, a Lieutenant in D Company, was in the third wave of the planned assault.

At 5.30 PM, the battalion was in position. Frederick stood ready with his men near the front-line saps. At 5.53 PM, the first waves — C and A Companies — moved into No-Man’s-Land and lay flat. At 6.00 PM, the artillery lifted, and whistles sounded. The men rose and advanced into a wall of fire.

Frederick’s final moments were never officially witnessed by a commanding officer. Instead, a series of reports came in through the Red Cross Wounded and Missing Bureau, based on interviews with men who saw him during the charge. While all agreed he was killed, their recollections conflicted sharply about where and when he was killed.

Private R.H. Leslie, quoting 1269 Private Glasset, said Frederick never even left the trench:

“Lieut. Hulks was killed instantly inside our own parapet before we went over.” — 3184 Pte R.H. Leslie

Corporal R.A. Thompson was with Frederick at the time, and claimed they had already reached the German trench system:

“We were sitting together in a ditch not a yard from each other when Lieut. Hulks was killed instantly, shot through the head. It was between the first and second German trenches.” — 1197 Cpl R.A. Thompson

Private H. Coulson did not witness Frederick’s death but saw his body after the attack:

“On the side of a big shell hole up near the German trenches I saw him lying dead.”— 916 Pte H. Coulson

Private H.C. Grieves, reporting second-hand from B. Stewart, said Frederick was killed in No-Man’s-Land:

“He was killed halfway between the lines at Fromelles by a shrapnel bullet in the head… There was too much machine gun fire to bring in the bodies.”— 3116 Pte H.C. Grieves

The 32nd Battalion succeeded in taking the German first trench line by around 6.30 PM, but the position quickly became untenable. Exposed, running low on grenades, and under constant bombardment, they were eventually ordered to withdraw.

At 4.00 AM on 20 July, the Germans launched a full counterattack. By 5.30 AM, the Australian line was collapsing. The retreat across open ground under machine gun fire was chaotic and deadly.“The enemy swarmed in and the retirement across No Man’s Land resembled shambles…”

Source: 1st Battalion War Diary, AWM4 23/48/12, p. 29

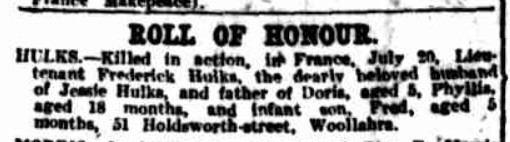

Frederick never returned. His name appeared on the casualty lists, first as killed, later as missing. Today, Frederick is commemorated at the V.C. Corner Australian Cemetery Memorial at Fromelles — one of over 1,200 Australians who died during the battle and have no known grave.

After the Battle

Frederick’s name first appeared on casualty lists as “Killed in Action” following the Battle of Fromelles. Multiple soldiers had seen him fall. Some described him being shot while leading from the parapet; others said they saw his body lying near the German trenches. But in the chaos of battle — and the even greater chaos of the retreat — his body was never recovered. That absence took a great toll on his wife Jessie.

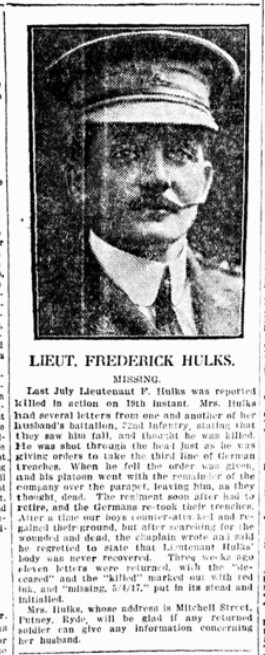

In the months that followed, Jessie Hulks, his wife, began receiving inconsistent and distressing information. Letters she had written to Frederick — eleven in total — were returned to her in April 1917. But what they carried was more than heartbreak, the envelopes bore handwritten alterations in red ink. Originally marked “Deceased” and “Killed”, these notations were scratched out, and replaced with “Missing 5/4/17”.

Each correction was initialled, giving it the appearance of official reassessment. But to Jessie, this was worse than confirmation — it was doubt. She placed a public appeal in the Daily Telegraph on 31 May 1917, seeking the truth:

“Last July Lieutenant F. Hulks was reported killed in action on the 19th instant. Mrs Hulks had several letters from one and another of her husband’s battalion, 32nd Infantry, stating that they saw him fall… He was shot through the head just as he was giving orders to take the third line of German trenches… The chaplain wrote and said he regretted to state that Lieutenant Hulks' body was never recovered. …Mrs Hulks, whose address is Mitchell Street, Putney, Ryde, will be glad if any returned soldier can give any information concerning her husband.”

Nearly a year after the battle, Jessie still held out hope that someone — anyone — might have seen Frederick in his final moments. That he might have been taken prisoner, or buried quietly, or survived without a name.

On 19 July 1917, the first anniversary of the battle, she placed a tribute in the newspaper:

“He fell a hero in the deadly strife,For King and country he laid down his life.Fame was achieved, and he had done his shareTo win those laurels rich and rareWhich now adorn Australia's loyal race —Not even time its glory can efface.”— Inserted by his devoted wife and children: Doris (6), Phyllis (2 years 5 months), and baby son Frederick (1 year 4 months)

In the years after the war, Jessie’s life was marked by both sorrow and strength. With three young children and no grave for her husband, she navigated grief in the quiet, determined way of many wartime widows. In 1920, she remarried, hoping to rebuild a life for her family. Tragically, her second husband died just two years later in 1922. Jessie married again in 1924, but throughout her life, her connection to Frederick never faded. He remained the father of her children, the centre of her earliest love, and the man she searched for across battlefield lists and returned mail. Though she would go on to live a long life, Frederick’s absence — like that of so many at Fromelles — was never truly filled.

Can You Help Us Identify Frederick?

Frederick was seen ”between the first and second German trenches.”

Frederick was 38 years old when he was killed at Fromelles — a career soldier, a father of four, and a man whose military experience stretched from the Indian Frontier, Asia and South Africa to the fields of France. If anyone could look after his men in Battle, Frederick had the experience. He was leading his men forward when he fell on 19 July 1916. Despite multiple witness accounts, his body was never recovered.

We believe Frederick may be among the unnamed soldiers recovered from Pheasant Wood in 2009. DNA testing is helping to identify those buried without names, and you may be the key to restoring his identity.

Even a distant family connection could help solve this case. We are especially seeking MT DNA from:

- Descendants of his siblings (Sarah, Rose, Kate, or Ethel)

- Descendants of his maternal cousins

- Anyone with family links to the Hulks, Cannell, Webb, or Humphries families from Middlesex, Hertfordshire, or London

If you think you may be connected to Frederick, please reach out to us through the Fromelles Association of Australia.

DNA samples are being sought for family connections to

| Soldier | Frederick William Hulks (1877–1916) known as Harry in the family. |

| Parents | Frederick Joseph Hulks (1850–1894) and Sarah Ann Cannell (1848–1920) |

| Siblings | Sarah Margaret Hulks (1875–1931) | ||

| Rose Mary Hulks (1879–1925) | |||

| Kate Maud Hulks (1882–1937) | |||

| Alfred Hulks (1883–1914) | |||

| Ethel Hulks (1885–1968) | |||

| Charles Hulks (1887–1930) |

| Children | Doris Jessie Christina Hulks (1911–1975) | ||

| Ivy Hulks (1913–1913) | |||

| Phyllis Irene Hulks (1915–2007) | |||

| Frederick Alfred Hulks (1916–2014) |

| Grandparents | |||

| Paternal | Alfred Hulks (1815–1861) and Mary Webb (1819–1886) St Albans, Hertfordshire | ||

| Maternal | William Michael Cannell (1822–1879) and Sarah Humphries (1823–1879) London |

Seeking DNA Donors

Contacts

(Contact: carla@fromelles.info or geoffrey@fromelles.info).

(Contact: army.uwc@defence.gov.au or phone 1800 019 090).

Donations

If you are able, please contribute to the upkeep of this resource.

(Contact: bill@fromelles.info ).