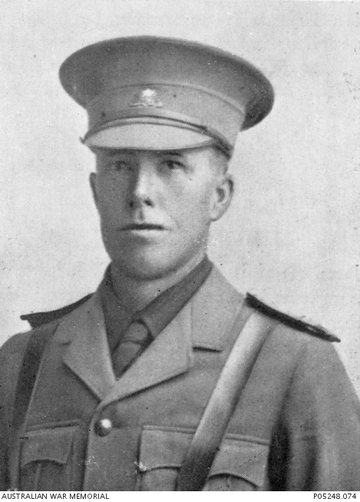

Aubrey LIDDELOW

Eyes unknown, Hair unknown, Complexion unknown

Aubrey and Roy Liddelow - Their Early Years

Aubrey Liddelow was born on 10 November 1876 in Tarraville, Victoria, the third of five children. His younger brother Roy was born on 2 April 1884. They also had a brother, Herbert, and two sisters, Annie and Elsie. Their parents were Arthur and Helen (née Clarke), British-born parents who were married in Ballarat.

Arthur was a schoolteacher and a school inspector with the Education Department. Music was obviously strong in the family, as each of Aubrey, Annie and Elsie were noted as solo performers in a children’s concert in Maffra in 1886 (Gippsland Times, 10 Nov 1886, page 3).

Aubrey followed his father into teaching. He attended Scotch College in Melbourne, South Melbourne College and Melbourne University and became a teacher at Melbourne High School. Aubrey and his wife, Fannie (nee Retallack) had a son, Aubrey, although he died in infancy.

After Roy finished school, he became an accountant and was working for the Consolidated Goldfields in Reefton, NZ at the time of his enlistment. Roy and his wife, Ruby (nee Danks), had a son, also named Aubrey, born in 1914.

The Call to War – Gallipoli

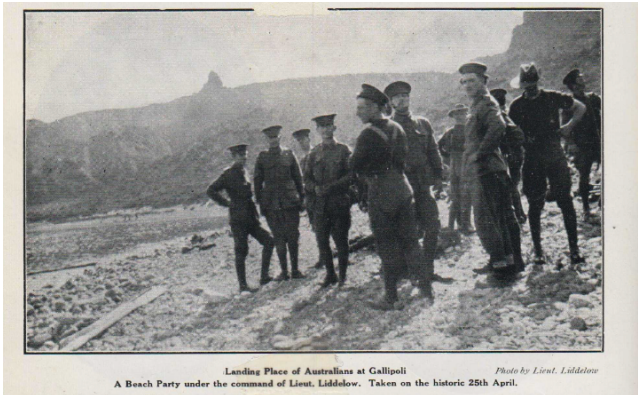

Aubrey was the first to heed the call to war and was early to enlist - 11 November 1914 - and was posted to the 7th Battalion as a second lieutenant. After a brief period of training at Broadmeadows, he embarked from Melbourne aboard HMAT Themistocles on 22 December 1914, heading for Egypt. Training and defence of the Suez Canal took place at Ismalia and Mena. On 5 April, the 7th Battalion embarked from Alexandria, heading for Lemnos and on to Gallipoli.

Aubrey kept a diary during 1915 which documents many of his experiences at Gallipoli. The whereabouts of the original diary is unknown but a hardcopy of typed transcripts is available at AWM (Accession No 1DRL/0417). Extracts from this material are included in the extensive writeup for Aubrey Liddelow on the Scotch College Melbourne World War 1 Commemorative Website and have been used in compiling this story.

While travelling with the convoy, he wrote in his diary:

‘Now we think of the old Phoenician and Grecian traders and Roman galleys and wonder whose old path we replough. Soon maybe we shall see even the “windy plains of Troy” – may even fight where Ulysses guided and Achilles fought, though I rather think ‘twill be upon the other side.’

He was correct, for he was headed to the Gallipoli side of the Dardanelles.

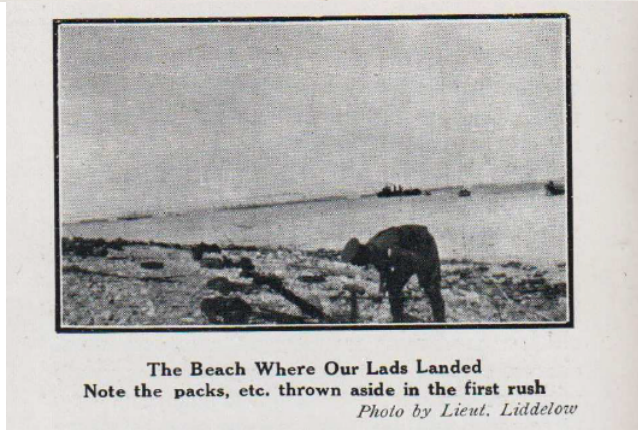

They were anchored in Anzac Cove at 4 am on April 25th and by 5 am the troops were rowing to shore. When they got 200 yards from shore, the enemy opened heavy fire on them from the trenches above. The Anzacs landed, though at a very high cost, and were able to finally return fire. Shortly after, the enemy retired and their trenches were occupied.

The hill above the landing was held long enough to recover the wounded, but the 7th were then forced to withdraw by 2 pm. The tally for the 7th Battalion was 400 killed or wounded. For his role in the landing assault, Aubrey was promoted to Lieutenant.

Aubrey found that he could cope with the horrible scenes around him, declaring that having to bury seven Australians and one Turk on the first night ‘made me feel not repugnant nor anything else, it was as a matter of course.’

In the days after the landing, Aubrey received a bullet wound to the left ankle and was sent to the hospital ship. In his diary he described unloading artillery ammunition at the beach one morning:

‘when I felt something hit my foot hard – as if a stone had struck me sharply. It didn’t hurt and I looked down, being quite surprised to see blood coming out of a hole in my boot. I walked along and soon limped a wee [sic], the Clearing hospital was about 50 or 60 yds along and in there I took off the boot finding that the beast hadn’t gone through.’

A kind English doctor tried but couldn’t find the bullet with a probe.

While on the hospital ship, Aubrey wrote of his recovery. ‘The Dr on shore said from 8 to 10 weeks the job would take – I hope not – the boys ought to be across the peninsula by then.’ Rather than being content with his wound, he wrote. ‘I lie here on the upper berth in No. 6 cabin of the Mashobra [a ship] wounded in the foot, bless you. I have done nothing, have ventured little, and am removed soon from the scene of the action.’ Aubrey was taken to hospital in Alexandria, Egypt and returned to the battalion on 26 June.

After a few days of ‘quiet’, shelling began again and the Turks were close enough to be heard speaking at night. Fighting continued and on 12 July, Aubrey was ‘slightly’ wounded in the eye and chest and was sent to hospital in Malta.

He returned to the unit in late October and was assigned the temporary command of a company. Aubrey was in the evacuation of the 7th Battalion to Egypt which was completed at 3.15 am on 20 December 1915.

Egypt - Roy joined Aubrey in a new Battalion

Roy answered the Anzac’s call while he was living in New Zealand, enlisting on 26 October 1915. He was assigned as a 2nd Lieutenant with the New Zealand 11th Infantry, H Company and departed from Wellington on 1 April 1916 on the “Maunganui”. He arrived in Egypt on 2 May.

Meanwhile, Aubrey was already in Egypt and had been promoted to captain on 20 February 1916. On 24 February, he was assigned to the newly formed 59th Battalion, a part of the AIF plans for expansion of the Western Front and organising the incoming troops resulting from the heavy recruiting programs back home.

A few weeks after arrival, Roy was transferred to the AIF (Australian Imperial Force) and joined his brother in the 59th Battalion on 31 May.

The Western Front – Fromelles

In June 1916, the 59th headed for the Western Front. They boarded the “Kinfaus Castle” in Alexandria and disembarked in Marseilles on 29 June. From there they took a train to Steenbeque, 35 kilometres from Fromelles, where they trained in the use of gas masks and learned to deal with the effects of large shells.

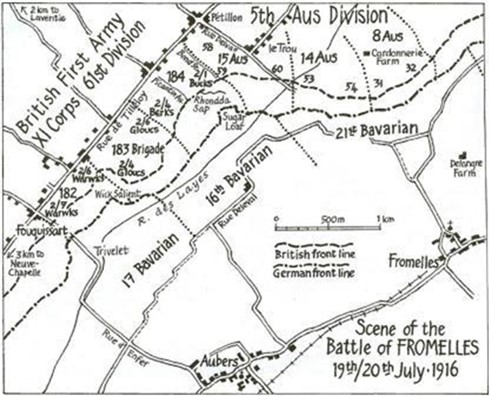

On 18 July, they were sent to the trenches to relieve the 57th Battalion where the front lines were under heavy artillery from both sides. Their position was near the Sugar Loaf salient, a prominent German machine gun emplacement.

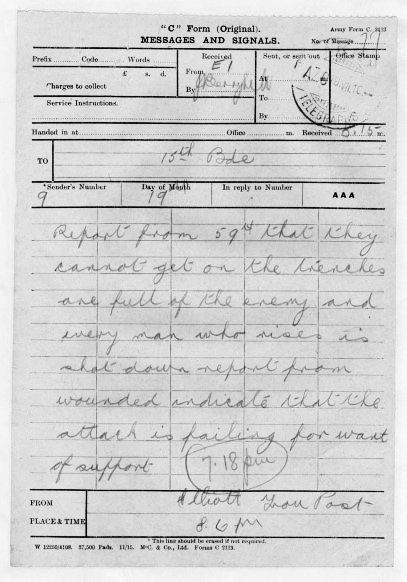

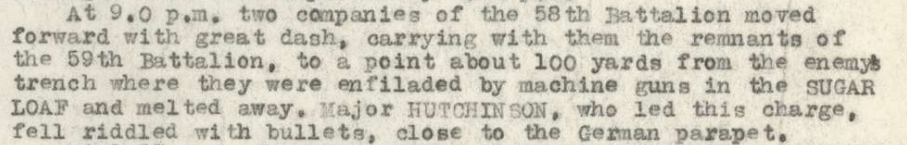

Their attack on the German lines began at 5.45 pm on the 19th. They were to attack with four waves at 5-minute intervals. There was intense fire from rifles and machine guns just a short distance away, as documented in the messages sent back to HQ just after the attacks began –

“cannot get on the trenches as they are full of the enemy”

“every man who rises is shot down”

The 15th Brigade notes on the battle captures the intensity of the early part of the attack – ‘they were enfiladed by machine guns in the Sugar Loaf and melted away.’

As one can well imagine with the intensity of the battle at this particular site, there was a great deal of confusion about just how far the soldiers were able to penetrate the German lines. The official reports indicate little progress was achieved, but individuals’ reports suggest there were some advances, with several of those sources noting Aubrey’s involvement.

One thing is clear about Aubrey, he had earned the full respect of his men:

“I was with the Captain from the time we went over our parapet until all was over, as far as this world is concerned, for a noble hero……On going over the parapet the Captain was wounded in the head, but he rose at once and led us on, for by that time he was in charge of the battalion. He reached the German lines with only a handful of men left, and in going over their parapet, he was wounded in the shoulder and again in the arm, but nothing daunted him.

In order to spare the few men remaining he withdrew us to a shell crater for shelter until reinforcements should arrive, when we could attack to better advantage. I was wounded, and had quite enough by this time; so I went to the Captain and asked him to return with me, as his wounds needed attention’.

According to this eyewitness, Liddelow replied, ‘I will never leave the men whom I have led into such grave danger and walk back again; we will wait for reinforcements.’ He then ordered the eyewitness back for treatment, but I had gone only ten yards when a shell ended the life of a hero and a gallant gentleman.”

George Martindale (1887-1922) in the letters in his book ‘Dodging the Devil’ (Hardie Grant Books, 2016) noted that:

“In my Company Commander I mourn the death of a brave soldier and a gentleman (Captain Liddlelow). He fell at the head of his Company “C” with his face to the enemy and his revolver in his hand. He served through the Gallipoli campaign where he was wounded, I saw him just before the word to “go over” was given, he nodded to me and smiled for we were friends. He knew he was “going west”. I read it in his face like an open book but he never flinched or faltered. While the Empire produces men of Captain Liddelow’s type it is safe.”

Aubrey also had the respect of his superiors. In Paul Cobb’s book ‘Fromelles 1916’ (2007) he records that General Pompey Elliott wrote:

“We are going to send out rescue parties tonight. It has been impossible during the day to get men out as the Germans have been shelling us badly but there is one officer we must try to get in. Poor Liddelow who came with me from the old 7th is out there badly wounded and we must get him in if at all possible…”

Roy’s involvement in the battle is much less documented. In the midst of the heavy fire, he was badly wounded in the right thigh, but was able to make it back to his own lines.

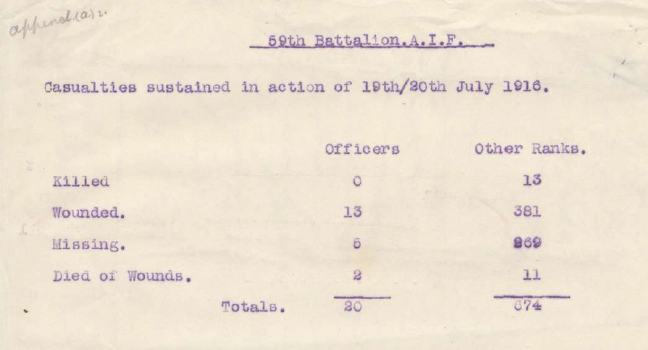

The toll on the 59th was huge – 695 soldiers killed, missing or wounded.

After the Battle – Roy

Roy was transported to London for medical treatment on 22 July. He was then sent back to Australia in November 1916, being eventually discharged in August 1917 as medically unfit from his wounds.

Roy’s service to his country was not done yet, however. He re-enlisted on 26 May 1918 and was assigned as a Lieutenant in the Special Service Italian Reservists and sent to London. This assignment lasted only a few months and he returned to Australia in October 1918.

After the war Roy and his wife, Ruby, had two more children, both daughters.

Roy returned to the mining/commercial business and became the Secretary of the State Electricity Commission of Victoria in 1919. This was the beginning of an electricity supply industry that was to become the lifeblood of industrial and economic development throughout the State. In 1921, the Commission was headed by Sir John Monash. Roy continued in his position, as well as in related national roles, until he retired.

Roy passed away on 25 February 1967 aged 82 years old. He was living in Ivanhoe, Victoria, his long-term residence.

After the Battle – Aubrey

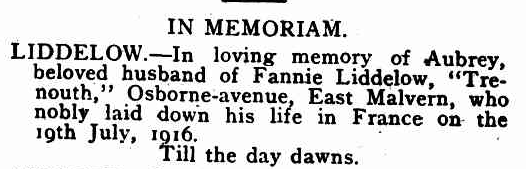

Aubrey was among the many missing soldiers from the battle. There was a long, long wait for the family.

They were notified in August 1916 that he was “missing” in battle, but there was no confirmation about his death, even with many communications with the Army from several family members.

It was not until November that his name appeared on a list of the dead from the Germans and not until 13 March 1917 that his identity disc was received. The family had accepted that he was dead long before the formal notification came. Indeed, whereas the formal notification took 12 months, personal items were despatched to his wife within 6 months of the point he was declared missing. Finally, an ‘in the field’ tribunal on 2 May 1917 declared him dead.

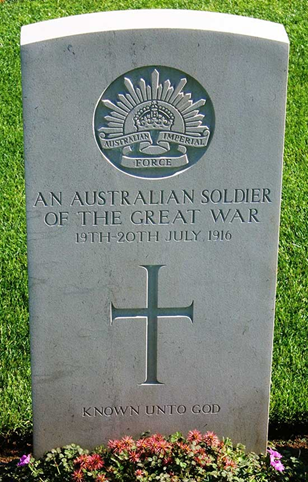

His final resting place, however, remained unknown.

His wife, Fannie, received on his behalf the Victory Medal, Star Medal, Memorial Scroll and King’s Message, British War medal and a Memorial Plaque. He has been commemorated at V. C. Corner in the Pheasant Wood Military Cemetery in France and at the Australian War Memorial in Canberra.

Aubrey is also commemorated in the soldiers' memorial window in St Andrew’s Methodist Church in Gardiner (Melbourne) which was dedicated on Sunday 24 November 1924. Aubrey’s name is one of five listed on the shield at the bottom.

Both he and Roy are also on the roll of honour of the Tarraville State School in Gippsland.

Gone but Not Forgotten

Over one hundred years after his death, a tribute concert for Aubrey was held on 21 August 2015 at the Melbourne Recital Centre. This featured some of Australia’s finest young musicians from the Australian National Academy of Music.

Closure for Aubrey?

In 2008, a discovery was made of a mass grave that had been dug by the Germans after the battle outside of Fromelles. It contained the remains of some 250 Allied soldiers.

With this discovery, there was an Australian Defence Force project to match up DNA of the soldiers in the grave with living relatives to be able to identify and honour the soldiers properly. As of this time, Aubrey has not been among those able to be identified. One Y DNA donor has been found but we are still seeking both MT and Y DNA donors. Can you help?

‘Till the Day Dawns’

Y and Mt DNA is still being sought from family

| Soldier | Aubrey LIDDELOW 1876-1916 |

| Parents | Arthur LIDDELOW b. 1837 Norwich, Norfolk d. 1910 Vic | ||

| Helen CLARKE b. 1850 d. 1933 Vic |

| Grandparents | |||

| Paternal | John LIDDELOW b 1798 Norfolk d. 1861 WA and Marianne SHALDERS b. 1801 Norfolk d. 1861 WA | ||

| Maternal | John CLARKE b. 1816 Scotland d 1904 Vic and Helen BORLAND b. 1814 Scotland d 1873 Vic |

Seeking DNA Donors

Contacts

(Contact: carla@fromelles.info or geoffrey@fromelles.info).

(Contact: army.uwc@defence.gov.au or phone 1800 019 090).

Donations

If you are able, please contribute to the upkeep of this resource.

(Contact: bill@fromelles.info ).