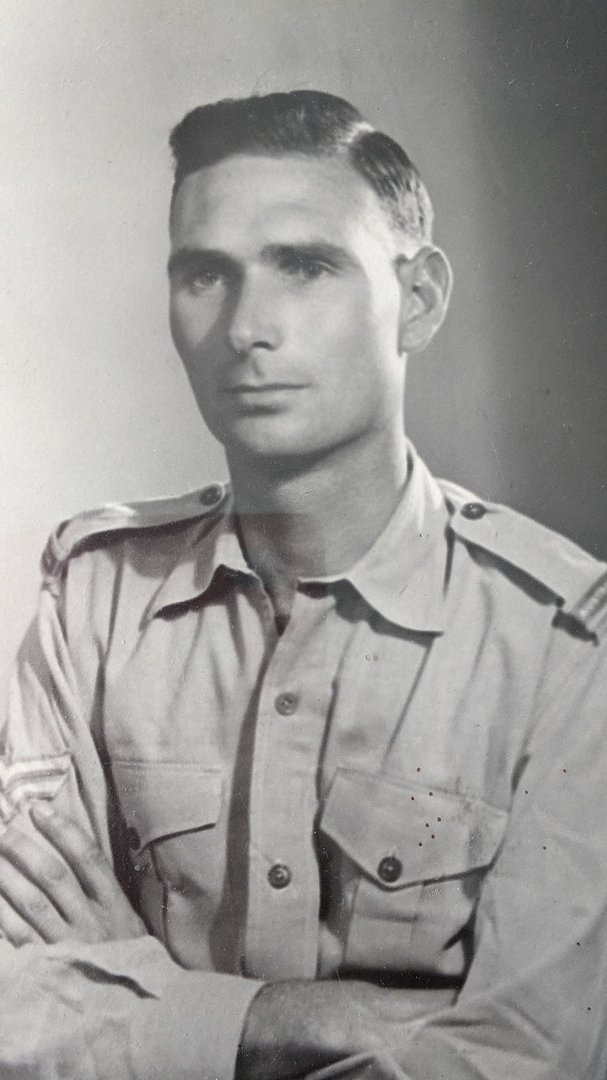

Harry Lowry MOFFITT

Eyes blue, Hair brown, Complexion fair

The MOFFITT family in Australia

In preparing this story, we must acknowledge the invaluable assistance of family members including Bron and Ed Chiu and Moffitt family connections across many parts of the world. We also thank our tireless and dogged researchers and the army for their ongoing support.

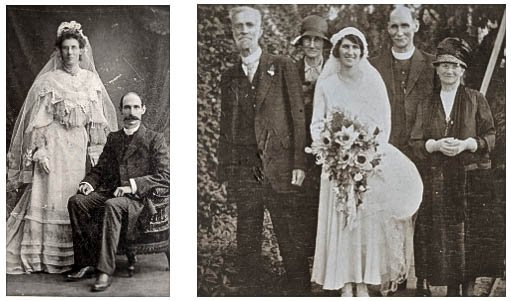

Harry’s parents were George Lowry MOFFITT, born 1847 in Enniskillen in County Fermanagh in Northern Ireland and London-born governess, Rebecca Susan MINNS (born 1852). They married in Victoria in 1876 and had three children - Mary (who died young), Ethel and Harry.

The Moffitt family built up a thriving drapery business initially in Werribee and Kyneton but later based in Gisborne. It seems young Harry was employed there for a time before he qualified as a public accountant and auditor. On qualifying, Harry took up a position with a well-known firm of Melbourne accountants, Densham and Sherlock.

There is also a likely family connection to the dressmaking and millinery store trading under the name Mrs Moffitt & Co at 192 Collins St, Melbourne in the early decades of the 20th century as that is the postal address that Harry gave on his application for a commission in 1915. It is probable that Mrs Moffitt & Co was run by Harry’s widowed aunt, Marian Moffitt, nee Press and her daughter, Dorothy Moffitt (1891-1975).

1915 Harry, a commission and new horizons

In March 1915, 32-year-old accountant Harry Moffitt enlisted and in June was granted a commission as second lieutenant having completed officers’ training school. He was assigned to the 21st Battalion and left Australia on the troopship HMAT A68 Anchises on 26 August 1915.

It was on this journey – probably his first outside Australia - that Harry met Army Nursing Sister Alice Ross-King, the woman he was to fall in love with and ask to marry him. Alice was 28 years old and had enlisted in 1914, nursing in Egypt since early 1915. In July, she returned to Australia on transport duty caring for soldiers wounded at Gallipoli.

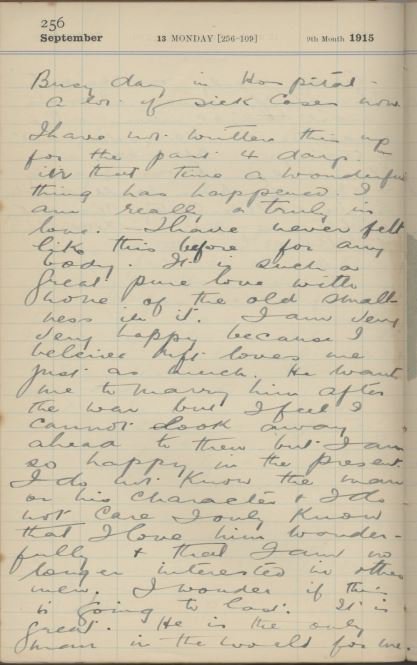

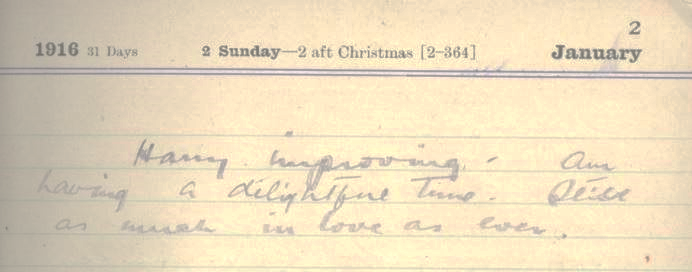

For her return to the war zone, Alice was allocated a berth from Melbourne on HMAT Anchises with some 1400 reinforcements, including 2nd Lieutenant Harry Moffitt. Just before the ship arrived in Fremantle to collect the West Australian new recruits, Alice’s diary (30 August 1915) first mentions a ‘Lieut. Moffat’ who she describes as a tall fair man with glasses and the common touch but more interested in her colleague Sister Martin than Alice herself. It is clear that, as one of only a handful of women on board ship (and later in a war zone), there was plenty of competition for the affections of the nursing staff. Alice’s shipboard diary has many references to Harry in the following weeks and maps the ups and downs of a blossoming romance until Alice writes in mid-September that:

“I am really & truly in love…… I am very very happy because I believe Mft loves me just as much………. He is the only man in the world for me.”

In this story of Harry Moffitt, we have confined mention of Alice Ross-King to her connection with Harry but we note that she has an incredible story in her own right serving as a volunteer nurse with the AIF in Egypt and France from 1914 until returning to Australia in 1919 to assist with setting up repatriation hospitals.

During her war service, she was awarded the Military Medal and was mentioned in despatches on more than one occasion - and later went on to serve in the second world war. Her personal diaries from 1915 to 1919 are available on the AWM website – but be warned that they are not always easy reading as she documents a horrific period of loss and suffering often from front-line war zones.

Her story was covered as part of the 2014 ABC TV mini-series ANZAC Girls that was based on the book by Peter Rees, The Other ANZACS (2008).

Egypt – war, illness and romance

On arrival in Egypt, Alice returned to her nursing duties at the Heliopolis hospital in Cairo and a week later Harry and the 21st sailed for Anzac Cove arriving about 12 October 1915.

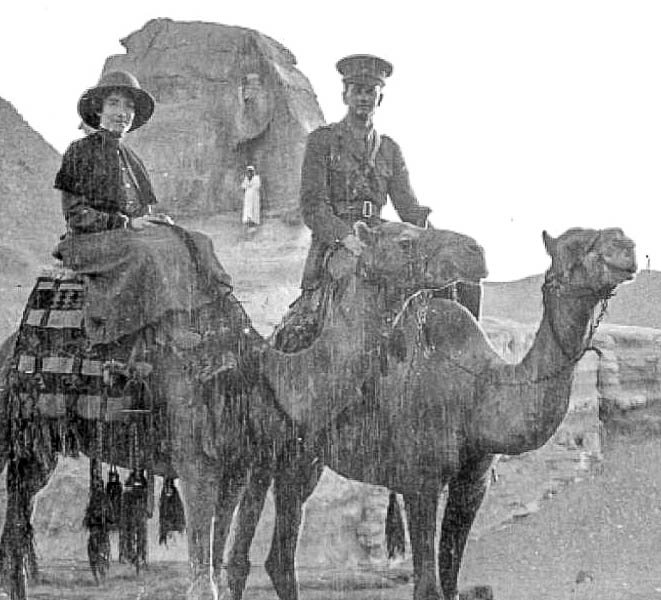

But this was not before Alice took the chance to show Harry the local sights including camel rides, dinners at the renowned Shepheard’s English hotel and trips to the pyramids, the Muhammed Ali Pasha mosque, the tombs of the pharaohs, and old Cairo.

For Harry, it was a whirlwind tour of Egypt’s highlights with his own personal guide.

At Gallipoli, the 21st Battalion were assigned mainly defensive roles at ANZAC Cove though they had to endure ongoing artillery and sniper fire. However, shortly after arrival, Harry came down with dysentery and typhoid and was hospitalised in Alexandria. His recovery was slow and Alice managed some visits and phone calls during November and December. They spent Christmas apart but managed to share the New Year celebrations together as Harry was transferred to the Heliopolis hospital with severe jaundice.

In mid-January, Harry began a six-week convalescence at the Helonan Convalescent Depot allowing Harry and Alice time together before Harry was discharged to duty in February.

February 1916: …..we sat on the balcony at Shepherds & talked of our future. There was a wonderful sunset a beautiful apricot glow. H said, ‘When we are married I’ll give you a dress that colour.’ He caught the 8p.m. train to the Canal and I have not seen him since.

Harry’s illnesses had earned him a recommendation that he be returned to Australia, but he refused. Did Alice’s presence in Egypt fuel Harry’s determination to remain?

With Harry back in camp and the hospital operating at high capacity, there were fewer opportunities to meet up. Rumours abounded that troops would shortly be heading for France and work was frantically underway to train the influx of new recruits and to bed down a reorganization of the AIF. Medical staff were also in the process of re-organisation and by April, Alice was in France waiting impatiently for an erratic postal service to deliver letters from Harry to hear when he too might arrive for the Western Front.

1916 On the warfront

At the end of March, Harry was assigned to 5th and 6th Brigades in Moascar and in April he was taken on strength with the 53rd Battalion at Ismailia. His permanent promotion to lieutenant was confirmed on 11 May 1916 and he was also assigned as adjutant to the Battalion.

The 53rd was soon called to support the Western Front. The 32 officers and 952 soldiers left Alexandria on 19 June 1916 on the Royal George. After arriving in Marseille on the 28th, they had a 62-hour train ride to Thiennes. It was noted that their ‘reputation had evidently preceded them’, as they were well received by the French at the towns all along the route. [Source: AWM War Diaries]

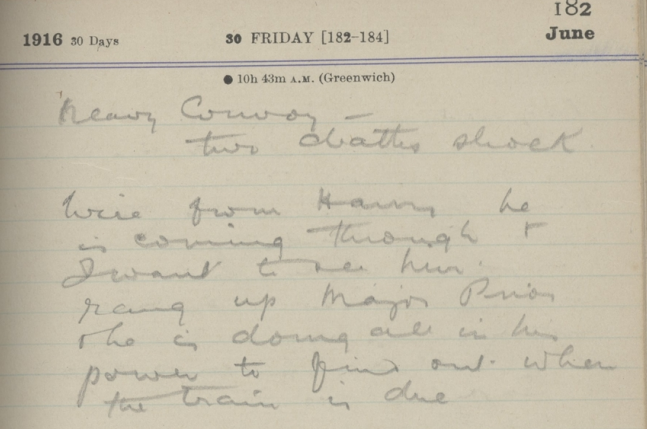

Harry had sent a wire to Alice to say he would be passing through on his way to the Front but sadly Alice’s attempts to see him did not succeed.

The Battle of Fromelles

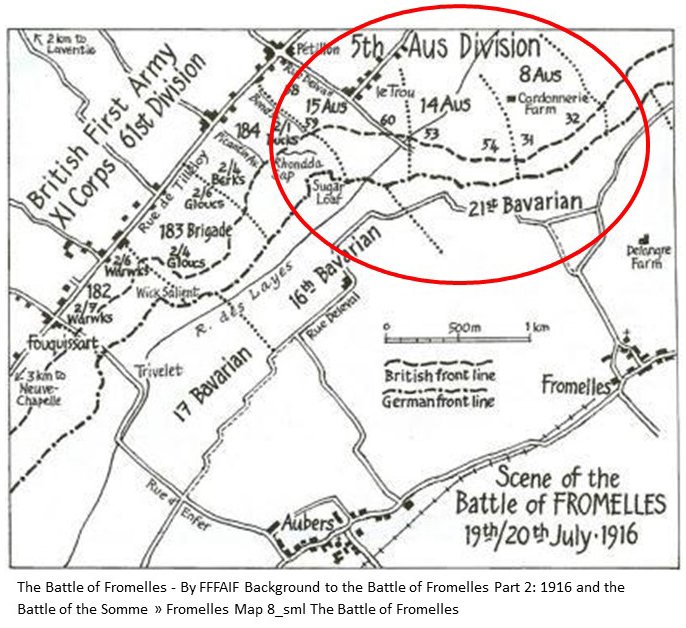

After leaving the train, the 53rd Battalion marched the remaining 35 kilometres to Fleurbaix. They were settled into billets on 16 July and then moved straight into the front lines on the 17th preparing for an attack, but it was cancelled by bad weather. They remained in the trenches on the 18th, in relief of the 54th Battalion.

By 11.00am on the 19th, heavy bombardment was underway from both armies. At 4.00pm, the 54th Battalion rejoined on their left; all were now in position and prepared for an attack.

The Australians went on the offensive at 5.43pm. There were four waves from the 53rd, half of A and D companies in each of the first two waves and half of C and D in the third and fourth. The first waves did not immediately charge from the Australian line, but went out into No-Man’s-Land and laid down, waiting for the British bombardment to lift.

At 6.00pm, the Germans were rushed, their front line captured, and the Australians headed for the second line.

Lieutenant-Colonel Ignatius Bertram Norris from Battalion Headquarters joined the troops and went over with the fourth wave. Historical records are a little conflicting, having Colonel Norris killed by either machine gun or shellfire. Norris reached the German front line but was struck down as he led the charge towards the enemy’s second line. Adjutant Lieutenant Harry Moffitt joined Private Frank Croft in trying to bring Norris back to their own lines but he was killed by machine gun bullets and it is reported that Harry fell across his commanding officer’s body.

According to Sergeant Patrick Lonergan (3112), 53rd Battalion:

“Mr Moffitt was with Colonel Norris, leading the Battn. The Colonel was killed by a shell and Mr. Moffitt called out for 4 men to bring the Colonel in. He had no sooner done so than he himself was shot in the back of the head and fell dead across the Colonel’s body. I was quite close by and saw this myself. I do not know if Mr Moffitt's body was afterwards recovered.”

Major John Joseph Murray, 53rd Battalion confirmed this report but added that Harry’s body was not able to be recovered:

“Lieut. MOFFITT was killed on the evening of the 19/20th July, while attempting (to) assist Col. MORRIS (sic), who was hit during an assault on the second enemy line in front of FROMELLES. Lieut MOFFITT was hit by Machine Gun fire and death was in[s]tantaneous. The portion was retaken by the enemy next morning and the body was not recovered.'

Private 3384 John P. MORLOCK, 53rd Battalion stated:

“…he saw the above killed at Fleurbaix on July 19th 1916 at about 6 p.m. Lieut. Moffitt was calling for volunteers to take back the Colonel's body and stood up in the trench. His head was blown off. Witness does not know if or where, the body was buried.”

The aftermath for Harry’s loved ones

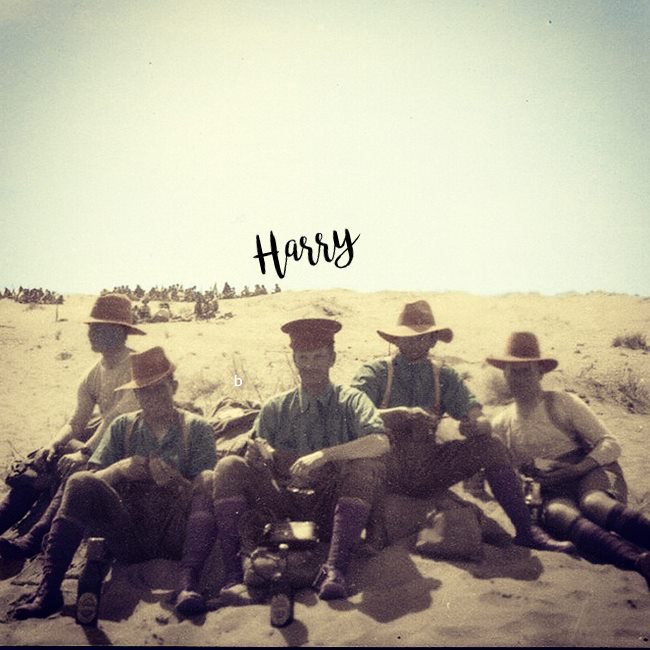

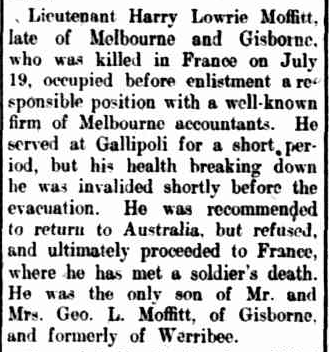

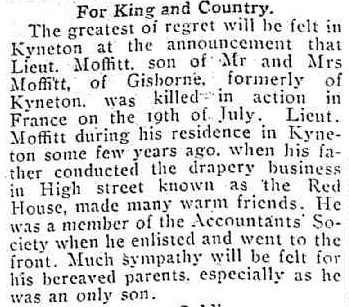

Two of the local news reports of Harry’s death in early August, a much shorter timeframe compared to many other families who had to wait for long periods for news.

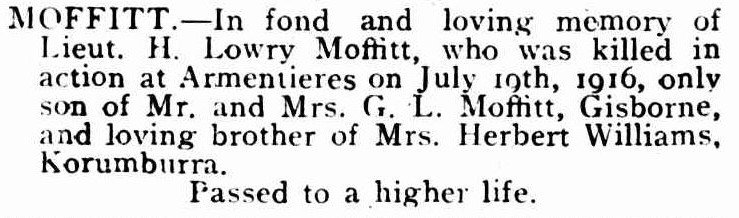

George and Rebecca Moffitt were notified in early August of the death of their only son in France but details about the circumstances of his death were limited. In December, family were advised that Harry’s name had appeared on a German Death List; this was an information exchange arrangement to help inform families about those taken prisoner or those killed in action and buried by German forces.

In mid-1917, the family also received Harry’s personal effects. This included his identification disc returned by the Germans as well as various items included within his trunk, suitcase and valise. After the war, his parents also received Harry’s service medals and memorial plaque.

It seems that Staff Sergeant Bernard Brown, based at the Harefield Hospital in England, acted as liaison for the Moffitt family in Victoria. He made enquiries on their behalf and passed on information from the Red Cross as it became available. It is likely that the family also heard some information direct from their son’s army colleagues.

Inquiries were also made regularly of the Red Cross by Alice Ross-King and by Major John G. Prior on her behalf.

Enquiries by all parties initially focussed on determining the circumstances of Harry’s death but by 1920 enquiries related to whether his burial place was known to authorities. Sadly, it was not.

We can only imagine the grief of Harry’s parents and sister on Harry’s death, but we have Alice’s diary to give some insight into her reaction on the death of her fiancé. In an entry dated 29 July 1916 (AWM, 1916 diary, page 96), Alice wrote:

“Well, my world has ended. Harry is dead.

God, what shall I do! Killed on the 19th. I heard the news last Tuesday. Major Prior sent it up.

I have been bowled completely over. Nothing on earth matters to me now. The future is an absolute blank.

I have kept on duty but God only knows how I have done so. Everyone has been most nice to me.

Oh my dear, dear love, what am I to do? I can’t believe he is dead. My beautiful boy. I’m hoping each day that the news will be contradicted.”

Alice’s diary traces her personal journey dealing with the ups and downs and the hopes and rumours that he might be alive or a prisoner, knowing that he had no grave, anger at the waste of life - and all the while trying to maintain the normalcy of working as nurse in the midst of a warzone. Almost impossible to imagine.

Alice wrote on occasions to Harry’s mother and later to his cousin, Dorothy Moffitt, but it is not known how the Moffitt family interacted with Alice over this time. Certainly, current day family were not aware of Harry and Alice’s romance and engagement until the ABC television program brought it to their attention. It may just have been the passage of time that led to the story of Harry and Alice passing out of general family folklore.

Harry – the search for DNA

Many of our stories contain a blend of information about a soldier, their family of 1916, and their family now. And this story will contain those elements too, but any story of Harry Moffitt would be lacking if it did not also include the story of the research undertaken to find his relatives who we hoped would supply DNA.

In genealogical terms, we often find roadblocks and rabbit holes and sometimes, catastrophically, an absolute "brick wall" that we cannot crack. But in Harry's case, we always found a glimmer of hope when some small piece of information came to light, and we “hared” off in a new direction. Only to find another roadblock, then another glimmer…… and so it has gone for seven long years. Thus, we have never reached a point where we thought that we had exhausted every avenue.

The search for donors for Harry is not unique. Many have been “on our books” for a decade with many stopped for varying reasons – false names, lack of records, “too common” names, DNA lines dying out, etc. But we do go back and check regularly to see if new information is available on the web or elsewhere – and importantly, we do leave a trail for other genealogists to follow and perhaps come find us!

The critical issue regarding the possibility of Harry being one of the 250 soldiers reburied at Pheasant Wood relates to first-person accounts that Harry fell across the dead body of his commanding officer. As Lt-Col Norris has been identified as buried at Fromelles, why not Harry?

In Harry’s case, our research hit the following critical roadblocks:

- DNA was not available in Australia when we commenced searching in mid-2014.

- In the case of mtDNA, we eventually established that a line probably existed in Canada. Following Harry’s mother’s maternal aunt (Priscilla Brierley) to Canada and down through her daughters' lines, we finally found a willing donor in Canada. For this we thank and acknowledge a wonderful researcher - Katrina Hodgson in Canada. Katrina did a truly remarkable piece of genealogical research as the relative found was a Mrs Smith, perhaps the most difficult name of all to locate!

- In the case of Y DNA, the roadblock was a Reverend James Moffitt living in Clones, Northern Ireland, a Minister of the Primitive Methodist Church. From Australia, we just could not crack the information barrier or find any research outcomes identifying family, especially parents. Connections of the Moffitt family based in England answered our plea for assistance and Helen Myerson and her wonderful detective lady cousins eventually travelled to Belfast where they went to the Public Records office to open the cache of letters donated to the PRONI by Rev James Moffitt’s family.

Moffitt relative and researcher, Ted Graham, has copies of the letters and provides the following information:

“The Public Records Office of Northern Ireland (PRONI) holds 65 letters referenced No. D1729 - Reverend James Moffitt Papers. These are primarily letters from 1858 tp 1896 between Rev James, his daughter Jane Anne (my great grandmother who emigrated to Melbourne, Australia) and her husband Edward Graham (my great grandfather). The correspondence relates mainly to family matters but include letters from friends of Jane Graham re her marriage and her home in Limerick.”

On reading through the many letters, tiny items of information were discovered, relatively meaningless when viewed in isolation, but together they created a meaningful picture. It was like piecing together a jigsaw puzzle. Rev. James Moffitt’s mother was born a Stokes; his aunt was a Mrs Thompson; his niece’s family named Brown went to America; and some of the Moffitt clan went to the USA and some went to Australia - including three of James’ children, namely, George (Harry’s father), Jane and John.

To bring all this disparate information together we used crowd funding monies to hire a genealogist from the Northern Ireland Genealogy Society. Kathleen McClure travelled to Northern Ireland and, in the absence of parish records, located the Magheraveelly graveyard near Clones, recording valuable information from much weathered headstones by trekking the graveyard and taking ‘rubbings’ where necessary. This included information from the graves of John Moffitt and Mary Stokes, Harry’s great-grandparents.

From that milestone, one of our own professional genealogists joined more of the dots, including those to America. We are blessed to have Mairead Crinion, living in Ireland, who has assisted with so many searches that we cannot ever thank her enough. She was soon dissecting this new information and was deep into this genealogical research, and excitedly wrote to FAA researcher, Marg O’Leary, "I don't think you realise how small a community these people came from!"

In another happy coincidence, while Marg was seeking donors for Harry, she was asked to research Alys Ross-King by her work colleague, a descendant of Alys. It was just a little later that the ANZAC Girls mini-series began on TV. While watching it, Marg came to the episode when Harry appears. "Oh no, the people making the series have highlighted a romance and I know he is going to die!"

So, Marg phoned her colleague and was informed “It’s all in Alys’s diary. It’s all true." That news was both unexpected, extraordinary, and understandable. Two young people going though war...and finding love, prepared to marry when the war was over...

No wonder Harry didn’t want to be sent home after his illness!

Our research has made great advances but Harry remains unidentified. We are still searching.

Family connections today

Bron Chiu recalls childhood visits to her Gran’s home with her sisters and cousins. At the time, Harry’s mother, Rebecca Moffitt, was in her 90s and also living there. Rebecca, Bron’s great-grandmother, lived to the age of 99 years and Bron only ever recalls her as being bedridden. “We younger ones - one cousin, and me and my two sisters - have no recollection of Harry being mentioned when we were at Gran’s. It was in Harry‘s bedroom that we slept if staying overnight. There was usually a Polly Waffle next to the bed. Harry’s stamp albums were in the room and my older cousins were allowed to look through them.”`

As noted earlier, the story of Alice and Harry was not a part of the family folklore but it just may have been that those who remembered were now gone.

Harry has certainly been remembered with Ethel naming her son Harry Lowry Williams in her brother’s honour.

The family have also made pilgrimages to Fromelles to honour Harry and his sacrifice with one visit in 2009 and another in 2016 at the Centenary commemoration. We hope that one day the family will get to visit a gravestone engraved with Harry’s name. We continue the search.

DNA is still being sought for family connections to

| Soldier | Harry Lowry MOFFITT 1883-1916 |

| Parents | George Lowry MOFFITT 1847-1934, born Ireland | ||

| and Rebeccah Susannah MINNS 1852-1952, born England |

| Grandparents | |||

| Paternal | Rev. James MOFFITT 1807-77, Clones, Fermanagh, Nthn Ireland and Mary LOWRY 1810-47, Clones, Fermanagh, Northern Ireland. | ||

| Maternal | James MINNS 1825-57, Chelsea, Middlesex, England and Mary BRIERLEY 1825-54, Chelsea, Middlesex, England |

| Earliest known Ancestors John MOFFITT 1781-1818 and Mary STOKES 1786-1866 of Clones on the border of Fermanagh and Monaghan counties. |

Links to other records

Seeking DNA Donors

Contacts

(Contact: carla@fromelles.info or geoffrey@fromelles.info).

(Contact: army.uwc@defence.gov.au or phone 1800 019 090).

Donations

If you are able, please contribute to the upkeep of this resource.

(Contact: bill@fromelles.info ).