The Aftermath

It is accurate to say that The Battle of Fromelles has an indelible and distinct association with two periods of time, in our perspective.

The first, is the Battle, and afterwards – from when the telegram boys across Australia delivered so many communications of terrible news, or a mate, or the Army wrote to a family. This period varies with individual families, but it is noticeable and recorded that most immediate families were so traumatised, that they never again, spoke of the lost loved one. That period ended with the deaths of immediate family.

The second period is when Lambis and others, managed to present a case which was accepted by the Army and Governments that a probably burial site, at Pheasant Wood, at Fromelles should be formally investigated. That period which commenced when with the release of information to the public in 2008 – 09 still has prominence to this day.

The Fromelles Association is naturally focussed towards this Battle, our soldiers and their families. We do acknowledge that Fromelles is but one Battle, amongst many, over many wars and conflicts, where the human costs have been identical.

The Battle of Fromelles is considered to have occurred between 6pm on the 19th and 9am on the 20th of July 1916. This is approximately 15 hours. The 5th Australian Division (officially) suffered 5,533 casualties,( it is of significance to acknowledge that this number was deliberately under-reported for some unknown reason) rendering it incapable of offensive action for many months; the 61st British Division suffered 1,547. The German casualties were little more than 1,000.

Formally reported as “The worst 24 hours to date in Australia’s military history” had taken place.

General Haking said after the battle:

“I think the attack, although it failed, has done both divisions a great deal of good.”

Many soldiers, wounded, taken prisoner or surviving felt differently, as did families and friends who were left to pick up the pieces and try to work out what happened on that fateful night. The cost of the battle would be felt for many, many more years, and factually, is felt strongly by families today.

At the end of World War 1, there were 1,299 unidentified Diggers, mentioned on the panels at VC Corner Cemetery, and another 40 mentioned on the panels at Villiers Bretonneux, lying in unmarked graves, buried under the soil of No Man’s Land, or exposed to the elements, at Fromelles, a world away from home. They had no identification, and no headstone; while the living had no place of pilgrimage, no place to grieve and certainly no personal recognition of their loved one.

To this date, many soldiers remain in unmarked graves. The discovery of soldiers at Pheasant Wood and the ongoing quest to identify soldiers and record their stories as an enduring legacy to the sacrifice they made is continuing.

More than two years after the battle, on the day of the Armistice of November 11, 1918, when the guns of the Western Front finally ceased fire, Charles Bean wandered over the battlefield of Fromelles and observed the grisly aftermath of the battle:

“We found the old No-Man’s-Land simply full of our dead,” he recorded. “The skulls and bones and torn uniforms were lying about everywhere.”

The Wounded

Over 3300 Australian soldiers were wounded at the Battle of Fromelles on the 19th and 20th July 1916. In the immediate aftermath of the Battle, many lay stranded in no man's land. As a ceasefire offered by the German Commander, was not accepted by General McCay, many soldiers risked their lives to help bring back the wounded. Some soldiers crawled back over the following days. For many it was longer as their mates could crawl out to give them water, and bandage them when they were unable to bring them in.

The majority of wounded were first treated at clearing stations, and dependent on the severity of their injuries, returned to service, or were transported to field hospitals.

For the severely injured, they were transported to major hospitals in France or to England and then some, no longer fit for active service, were returned home home to Australia.

Some soldiers like Roy Arbon, a stretcher bearer were wounded in action. Roy was transferred from clearing station to field hospital, to hospital ship and then to an English hospital in Nottingham, sadly he died of his wounds the same day.

"Seeing by The Bendigonian dated 3rd August the account of the death of our mate, Private Roy E. Arbon, whilst in action in France, the cause of death being unknown, we should like you and all our friends over there to know that it was while taking a wounded comrade to the dressing station that he sustained his injuries. His mate was killed outright, and he himself was wounded in eight different places. This happened during one of the severest bombardments that we have yet had. Stretcher bearing is one of the toughest jobs in the line, but whenever wanted Private Arbon was always ready and waiting to do his best"

You can read Roy's Soldier Story here

Sergeant Samuel Archie Saunders was hit by gunshot to the arms and chest. Unlike many men left in No Man’s Land, he was lucky to be retrieved and taken by stretcher bearers of the 14th Field Ambulance to one of the twelve Regimental Aid Posts, six of which had been moved forward to 500 yards behind the assault battalions’ lines. They were overwhelmed with wounded, dying and dead – reflecting the situation in the communication trenches and No Man’s Land through which they pierced. The indescribable scenes of carnage continued over the ensuing days, when many men gave their lives rescuing comrades, as enemy fire persisted.

“only the 14th Brigade (all NSW) - in the centre position of the Australian line - could be described as being successful”. But the battle was a disaster, resulting in extremely heavy allied casualties, including over 2,000 Australian dead: still the worst 24 hours in Australian military history.

On 21 July, “the Brigade moved back into their billets at Bac-Saint-Maur” and then, “took the Fleurbaix sector again on the evening of 22/23rd July.” The next day, Saunders was evacuated from No. 1 Canadian Casualty Clearing Station to a base hospital."

You can read Samuel's Soldier Story here

The Prisoners

The Fromelles prisoners constitute the second largest group of Australians to be captured in a single engagement. In part, they were too successful in gaining ground, but without sufficient support. Having survived the devastating machine-gun fire sweeping no man’s land, groups along the 8th and 14th Brigade fronts succeeded in breaking through the German front line.

Much to the chagrin of those still willing and able to fight, the order to surrender was passed along the 14th Brigade front, and a white flag produced by an Australian officer sapped whatever morale remained. When the Germans recaptured the front line, those preparing for a final stand or attempting to withdraw were also taken prisoner.

Captain Charles Mills, was taken prisoner of war on the 20th July 1916. He was interrogated and sent to a German Prison, he and fellow officers were paraded through Lille as an example. In 1917 he was repatriated to Switzerland under an agreement suggested by the International Committee of the Red Cross and the Swiss government, Germany, France, Britain, Russia and Belgium signed an agreement in 1914 regarding prisoners of war (PoWs). The agreement stated that captured military and naval personnel who were too seriously wounded or sick to be able to continue in military service could be repatriated through Switzerland, with the assistance of the Swiss Red Cross. In 1919, He was repatriated back to England, and from then on was seconded to work with the Australian and International Red Cross to repatriate Prisoners of War, in London, then Berlin. He travelled to Germany to find missing Australian soldiers (approximately 35) remaining after the war.

You can read Captain Charles Mill's Solider Story here

The treatment of prisoners varied greatly, but they generally fared better the further away from the front line they were moved. After capture, officers were separated from their men, the latter being paraded through the streets of Lille.

The Fromelles prisoners were gradually distributed across Germany, where they were imprisoned in camps alongside British, French and Russian troops.

Source: Pegram, Aaron, “Australia’s Fromelles prisoners”, Wartime 44 (2008) 23 , Australian War Memorial

“It was the energy and push of the Australians that had been the cause of his becoming a prisoner, for they had pushed forward too far, and some of them were surrounded and captured.”

Private Henry Westerway was one of those gassed and eventually taken prisoner by the Germans – one of 470 prisoners taken. Henry was repatriated back to England. He met his future wife during his convalescence. They married in England. You can read his Soldier Story here

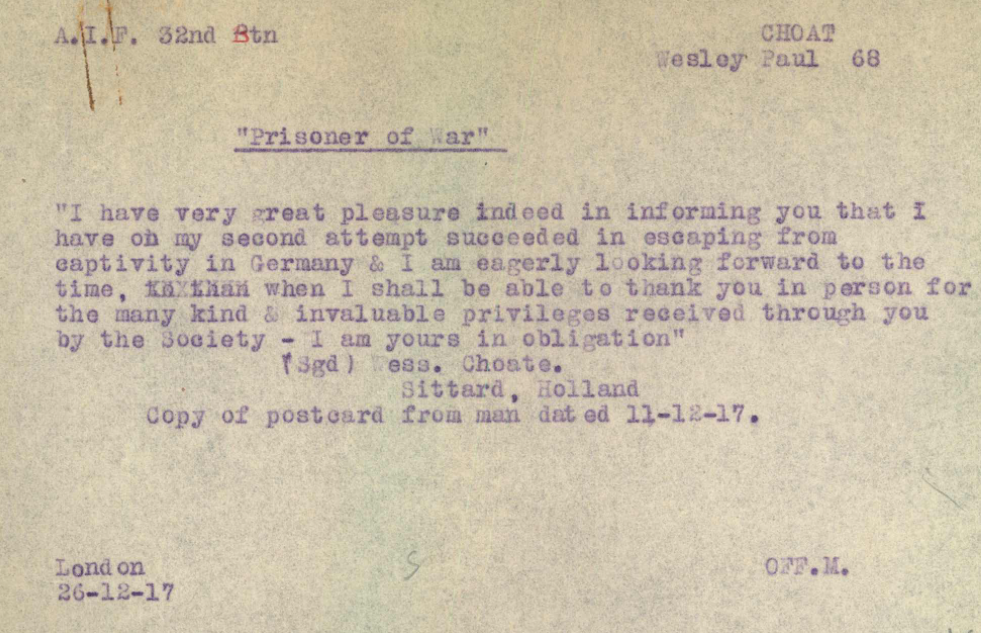

Wesley Choat was taken prisoner at the Battle, his two brothers Archibald and Raymond were killed in action, in 1917 on his second attempt he successfully managed to escape with another prisoner James Pitt. You can read Wesleys soldier story here

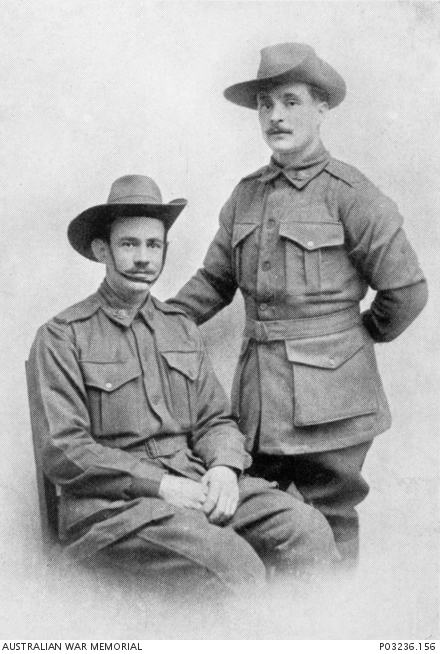

The Survivors

The Australian 5th Division was unable to mount offensive operations until reinforcements arrived to bring the various battalions and support units to somewhere approaching full strength. This occurred towards Christmas 1916. Service men and women of the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) were being repatriated throughout the war. By the time the Armistice was signed in November 1918, some 93,000 personnel were already back home in Australia. Almost 75,000 of the men deemed 'unfit for service'.

We know that over 60,000 Australians were killed in action, and we are aware that another 60,000 are reported as dying before 1928. Anecdotally, information also points to an extraordinary number who died an early death, and/or who suffered from the then untreated/unrecognised PTSD.

On return to Australia, soldiers of the 5th Division met every year on, or close to the 19th July, to quietly remember the fallen.

It is noteworthy that despite the Battle of Fromelles being “overlooked” by so many in positions of power, where Fromelles might have been championed – it was up to the soldiers and Officers who served at Fromelles, to champion to acknowledge what they considered to be their “Battle”.

Source: Australian War Memorial

The only record available, of these meetings is contained within the appendix of Geoffrey Benn’s book – Fromelles , A Hundred Years of Myths and Lies, and occupies some 30 odd pages of abbreviated notes.

Soldiers like Albert James, wounded in the shoulder, were initially given “triage” treatment, and then were operated on, more extensively, later.

On the 26th July, my 21st birthday, I was operated on. After being X-rayed and the position of the shrapnel (which was inside) found, the doctor soon had it out, but he put an awful gash in my back from the top of the shoulder right round under the arm, where he made a big hole— almost got an egg-cup in it. For a long time I had a big tube right through me, but, thank God, I have it out now. I cannot use my arm yet to any extent, but it won't be long before it is right, so the doctor says. This was a nice little birthday present, wasn't it?

These good people treat Australians as if they were lords or something else. They cannot do enough for us. After I was wounded I lost everything I had, even my bit of money, so am stony broke, and the authorities won't pay us any until after we are convalescent. I suppose you will be putting my photo in 'The Argus' now as a wounded soldier? Ha! ha!

You can read Albert's Soldier Story Here

Once back in Australia, one critical challenge was who should help care for returned soldiers and provide their aftercare.

Early in the war, care was left to voluntary patriotic organisations. They sought to raise money at the local level to support returned soldiers. By 1918, A Repatriation Department (Later the Department of Veteran Affairs) was set up to offer support with housing, sustenance, jobs and retraining. A soldier settlement scheme was established and administered by the states.

Unfortunately for soldiers who suffered from what we would now call PTSD, support was often inadequate and soldiers were often placed in Mental Asylums or Repatriation Hospitals for extended periods. Soldiers who returned home from World War I faced a number of problems, including unemployment, mental illness, and physical complications, like amputations, paraplegia, lung problems, and blindness. Treatment for injuries, both physical and mental, was crude and sometimes did more harm than good.

Soldiers mourned the loss of compatriots and friends: Private Stanley Stephens, a chum of Private Claude Yeo, of the 30th Battalion, wrote:

"Everyone was creeping over the parapet and leaving it. I had to get out, too, or get caught by the Germans. I never saw Claude or heard of him again. I would give something to know where he is. He may have caught the next bomb after mine, or he may have got away alright, but I could not find out. I crawled over to our trenches. This was the fifth time I had gone through a curtain of fire unscathed. Then the Germans attempted to come across to our trenches, so I had to stand to for an hour and work the rifle. Then I sat down against the wall for an hour and could not get up the ambulance had to remove me. I only know about seven who got through unhurt. There may have been more, but I went away with the wounded in the motor car that night. There were thousands of wounded sailing from Boulogne to Birmingham."

You can read Claude's Soldier Story here

The Soldiers Lost and Missing

Approximately 2000 Australian Soldiers were to lose their lives following the Battle of Fromelles. Many were listed as "Missing in Action" or " Fate unknown". Families wrote multiple letters to authorities looking for answers. There was much confusion and misinformation throughout the war as evidenced in the soldiers' official records. Correspondence between the Red Cross, Base Records, Soldiers still on duty and various other auxiliary agencies paint a picture where information was scarce and often delayed. Families could wait months to years to learn the fate of their soldier. Red Cross were consistently empathetic and gave their own intelligence gathering and provided feed back to families when the Army did not. Sadly, many of these reports were not gathered until late in 1916, or throughout 1917. They were gathered generally in hospitals, and often were 3rd person accounts.

Additionally, soldiers talking about a mates demise, would naturally try to spare families from additional suffering, and understate the manner of death.

Court Of Inquiries - 1917

Throughout 1917, Court of Inquiries were held, usually in the field, to ascertain whether soldiers were missing or Killed in Action. It was at this point, most families were finally notified by the War Office as to the fate of their soldier. Evidence was gathered from various hospitals, prisoner of war information and soldiers recollections to decide the fate of the soldiers.

The Families

For the families of soldiers, mates often wrote of their death, or possible capture, for whatever reasons, the Army waited or had to wait till late 1917 to formally advise families that a son was no longer considered MIA, but was, in fact, KIA. This conflict of information was agonising. And it is documented that many direct family, passed on the 19th or 20th of July, in subsequent years.

(1892-1916)

In mid-August, William Gordon Starr’s family were notified of him being listed as ‘missing’ but no further details were available. In October 1916, the family hopes were raised that he’d been taken prisoner when they received a cable to the effect ‘All well’ and signed ‘Starr’. They were at a loss to know which son had sent it. A Cousin wrote from France ‘She can’t know he is missing’.

In July 1917, a court of enquiry was convened in France and after hearing witness statements now contained in the Red Cross files, it was determined that Private William Gordon Starr, 1291, died 20th July 1916.

Thirteen months after his death, the family were notified and again it was the local press that gave more details though it stated incorrectly that he was invalided in England.

Hannah Starr (William’s Mother), corresponded with the War Records office for over 5 years trying to establish what happened to her son. In July 1920 she wrote following receipt of a generic form A regarding inscriptions for his death:

“Sir, I do not wish to have any thing to do with this form. My son was reported to me by the military as missing from 23 July 1916, then reported Killed in Action and I have heard nothing further from the military and so far as I know His (sic) body was not found. I received nothing belonging to him.”

You can read William Gordons Starr's Soldier Story here

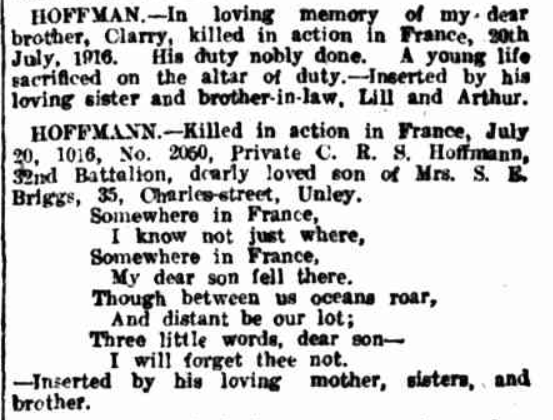

Sarah Briggs, having been officially advised in December 1916 that her son Clarence had been killed in action, wrote a letter to the Officer in Charge on 5 April 1917, asking about her son’s death:

“He was reported missing in July & in December reported killed. It is very hard for a mother to take for granted she has lost her son just on the word of a cable. Could you let me know if they found him or his disc & if I am entitled to any Private articles he may have had in his kit bag as I have had no word relating anything about his deferred Pay. I feel very anxious and would be very grateful to you if you could let me know anything at all about him.”

Many families were grief stricken and posted sometimes yearly in memoriums in newspapers of the day, quite often with poems to remember them fondly.

You can read Clarry's Soldier Story here

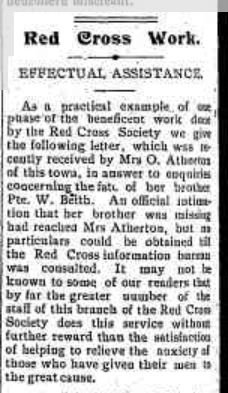

The Red Cross Wounded and Missing Enquiry Bureau

After the battle, word seeped out to the families of the tragedy. For some families they were told straight away, telegrams coming through from friends or family at the battle. Others were contacted by the Australian Red Cross Wounded and Missing Enquiry Bureau.

The Australian Red Cross Society was a subsidiary of the British Red Cross and followed its lead in many areas. It established its own Wounded and Missing Bureau in October 1915 in Cairo (later moving to London) and Prisoner of War Department in July 1916. Information on prisoners of war was gathered through sister organisations in enemy and neutral countries. Enquiries about wounded and missing soldiers from their families were investigated by searchers – usually employees of the British Red Cross - who examined official lists and interviewed soldiers' comrades who might be in hospital or on active service. Reports back to families were often in blunt language with graphic descriptions, and sometimes contained contradictory information. The intention was to provide as much information as possible.

William Beith's Sister shared her story with the local newspaper. You can read William's story here

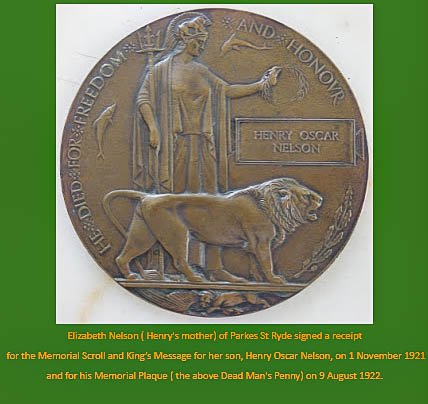

The "Dead man's penny"

Officially named the World War I Memorial Plaque, it is a commemorative medallion or memorial plaque which was presented to the next-of-kin of the men and women who died during World War I. The plaques were designed and produced in Britain and issued to commemorate all those who died as a result of war service from within the British Commonwealth.

Henry Oscar Nelson's Penny was returned to his family nearly 20 years after it was lost.

For more than twenty years, the plaque had been in the care of Lynne Crawford who found it in a box she had bought during the 1990s at a garage sale in Bingara, northern New South Wales. Keen to find Henry’s family and return the plaque, Lynne sought the help of her neighbour and researcher, Helen Cornish, who made contact with the Ryde Library and various others, including the Ryde Goes to War project team. Eventually, the Ryde District Historical Society contacted a great niece of Henry Nelson’s, Judy Hanlen and in March 2013, more than ninety years after its issue, the Dead Man’s Penny was presented to Judy as a representative of the broader Nelson family.

You can read Henry Nelson's Soldier Story Here

In 2020, FAA researchers identified that a "Dead Man's Penny" belonging to Percy Greenwood, a soldier killed in action on 20th July 1916. The Fromelles Association of Australia quickly arranged to purchase it to ensure it found a home where Percy’s story could be told and his memory preserved.

With the help of Australian and United Kingdom researchers, the penny is now safely in the hands of the Association and plans are underway to find a place where it can be preserved and Percy’s contribution honoured. It is also hoped that we can use the penny to generate publicity in an attempt to locate donors as, despite years of searching, we are still in need of Y DNA to help identify Percy.

You can read Percy Greenwood's Soldier Story here

The War Medals issued to soldiers after the war were often sent back to the closest next of kin. Various letters in official files, tell the story of the order of relationship that the Army followed in distributing the medals. A large portion of medals remain unclaimed to this day as it was not always easy to establish the next of kin. To this day, attempts are frequently made to return medals to families where they have been lost over the years.

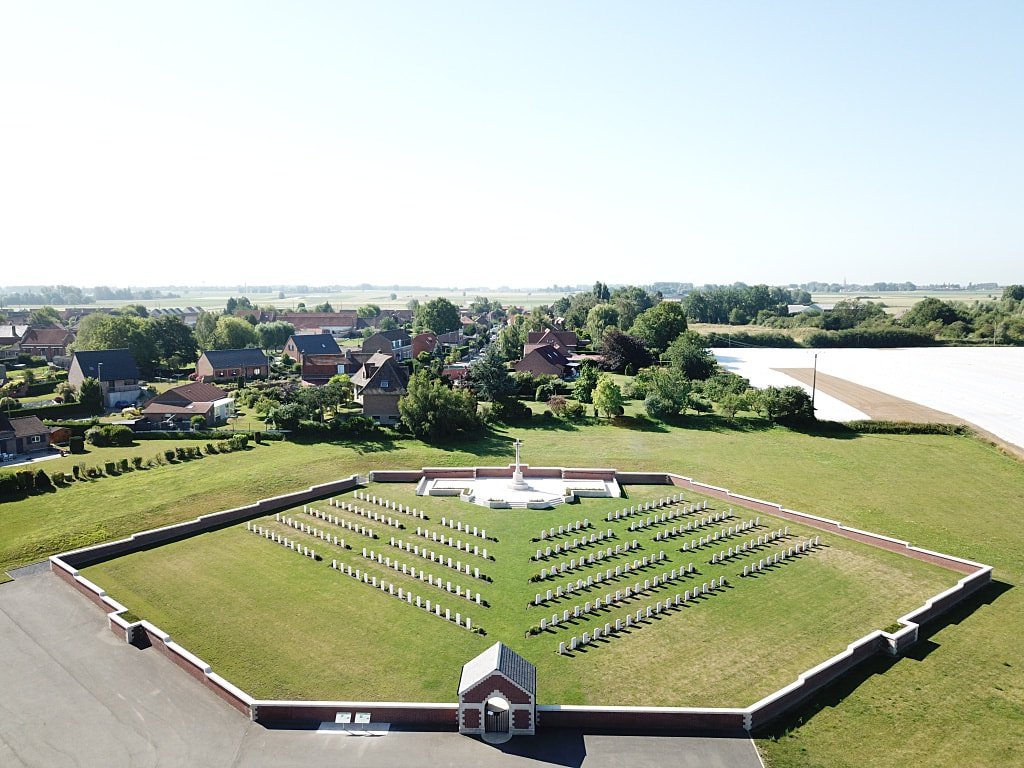

VC Corner

In 1921, Soldiers’ remains were collected from the battlefields. Soon after, Soldiers remains were gathered from no-man’s land to construct VC Corner Cemetery, the only solely Australian war cemetery in France. It is also the only cemetery without headstones. There are no epitaphs to individual soldiers, simply a stone wall inscribed with the names of 1,299 Australians who died in battle nearby and who have no known graves. The unidentified remains of 410 unknown soldiers are buried in mass graves under two grass plots in the cemetery. When soldiers are identified, their names are removed from the list of unknown graves.

Pheasant Wood Cemetery

In 2007, following persistent research by retired Melbourne teacher, Lambis Englezos and his team, archaeological investigations began to uncover the remains of some 250 soldiers who were buried in a mass grave at Pheasant Wood by German troops in the days after the Battle. Between 30 January and 19 February 2010, the remains of 250 soldiers were reinterred with full military honours in Fromelles (Pheasant Wood) Military Cemetery, newly constructed by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission. Of those, 166 have been identified, 84 are remaining. Those identified through DNA research have been given a name, and a place in our nation’s history. The research continues to identify and remember these soldiers.

Musee de Fromelles

On June 18, 2014, the Museum of the Battle of Fromelles opened its doors. The origins of the museum go back to 1990 when the Association for the Souvenir of the Battle of Fromelles created a first associative museum, housed at the town hall. A large collection of objects and documents are kept here regarding the Battle and the soldiers who partook. The museum organises a variety of cultural activities connected to the history of the First World War and Fromelles.

The Australian Memorial Park

The Australian Memorial Park is a World War I memorial, located near Fromelles, France commemorating Australians killed during the Battle of Fromelles. "Cobbers" is a prominent 1998 sculpture by Peter Corlett of Sergeant Simon Fraser rescuing a wounded compatriot from No Man's Land after the battle. A replica of the sculpture is in the Shrine of Remembrance in Melbourne, Victoria.

Australian Army - Unrecovered War Casualties (UWC-A)

UWC-A investigates all notifications of the discovery of human remains that are believed to be those of Australian soldiers. The unit also responds to reports or information that may lead to the recovery of human remains of Australian servicemen.

After two years of careful investigation, excavations, recovery and identification work by a joint Australian and British Fromelles Project team, 250 Australian and British Soldiers were reinterred with full military honours in individual graves at the Fromelles (Pheasant Wood) Military Cemetery in 2010. The UWC-A has managed the DNA collection, identification and registered interest of families for Soldiers killed in action at Fromelles.

The Fromelles Association

Founded in 2010, The Fromelles Association is a group of volunteers who are searching to identify missing soldiers who fought in the Battle of Fromelles and who were buried in mass graves by German troops. Many soldiers were buried in what was then No-Man’s-Land, and in un-named plots after the Battle of Fromelles.

Since the discovery of the mass graves, it is our aim to have each headstone named with the soldier who lies beneath. The Association seeks DNA samples from possible descendants through our research of family histories and war-time records.

The Fromelles Association is dedicated to researching the lives of these soldiers and detailing their stories in a digital living history, so future generations can gain an insight our Fromelles history, both good and bad.

In 2020, work started on capturing stories of the soldiers’ lives in a comprehensive online record so that the memory of their sacrifice is not forgotten.

Found at Last

The search continues to identify soldiers killed in the Battle of Fromelles. For the families of today, who grew up with stories of their soldier to the ones who found out through this project, the common link is that identity and dignity can be found and the soldiers can be remembered with honour.

Researchers from the Fromelles Association supported David Andersons family to identify him.

"After all the research, however, I do now feel like I know David personally, in a way. I have his ring, I have his medals, I have visited his graveside in a proper cemetery with his name on a headstone. I and my family are immensely grateful to the Australian Army UWC Unit and to the Fromelles Association of Australia for making this possible. Closure is a wonderful thing. We now feel we can lay David to rest in our hearts."

You can read David's Soldier story here

Barbara (Henry's Great Great Grand Niece) recalls on Henry Bell being identified in 2018:

“When I received the formal notification that my long-lost great uncle, Henry Bell, had formally been identified using DNA, I remember initially feeling disbelief. I think I may have asked ‘Are you absolutely sure its him’? After so many years, a positive result in identifying Henry had seemed to be slipping further from reach. I dared to hope such a thing was still possible. However, only days before I was notified, I had sent some old stamps from the early 1900’s (originally sent from Henry’s sister) to Canberra in the hope that they may possibly help solve the conundrum as to who Henry was. Miraculously, they were not needed after all! Yes, Henry had certainly been identified and any doubts faded to absolute joy! Finally, finally the missing piece of the jig saw puzzle had been put into place! Private Henry Bell would rest with a headstone bearing his name in the little cemetery in Fromelles where he fought and died for his country over a hundred years ago.”

You can read Henry Bells Soldier Story Here