The Red Cross and the Prisoners of War

What happened to the Australian prisoners captured at Fromelles?

Australian Soldiers taking part in the the Battle of Fromelles in July 1916 were captured by the German Army and interned in Prisoner of War camps. Many were wounded and captured behind enemy lines. They were marched through Lille, interrogated, and sent to prisoner of war camps across Germany held lands.

How many Australians were taken prisoner at Fromelles?

Approximately 478 Australians were captured by German forces during the battle — the second-largest group of Australians taken prisoner in a single WWI engagement.

How were prisoners treated by the Germans after Fromelles?

Treatment varied. Many wounded prisoners received little immediate care and were marched for hours without rest. Conditions improved once they reached camps deeper inside Germany, where Red Cross parcels and international oversight offered some protection.

What did the Red Cross do for Australian prisoners of war?

The Australian Red Cross tracked prisoners, sent food and clothing parcels, facilitated correspondence with families, and advocated for their welfare. Their support was crucial for the survival and morale of prisoners held in Germany.

Who was Mary Chomley, and why was she called the "Angel of the Prison Camps"?

Mary Chomley led the Australian Red Cross Prisoner Of War Department in London. She personally wrote to every captured Australian and managed a team that sent thousands of parcels and letters. Soldiers affectionately called her the “Angel of the Prison Camps” for her dedication and care.

What was Vera Deakin’s role during WWI?

Vera Deakin, daughter of Prime Minister Alfred Deakin, founded the Australian Wounded and Missing Inquiry Bureau. Her organisation answered thousands of family enquiries, often with more clarity and compassion than official military channels.

Who was Captain Charles Mills, and why is he significant to the story of Fromelles?

Captain Charles Mills was an officer of the 31st Battalion who was captured during the Battle of Fromelles on 20 July 1916. After being wounded and taken prisoner, he was interrogated and paraded through Lille before being interned in a German POW camp. In 1917, he was repatriated to Switzerland under a Red Cross agreement for seriously wounded prisoners. Following the war, Mills worked with the Australian and International Red Cross to help locate and repatriate missing Australian soldiers in Germany. His story highlights both the experience of Australian POWs and the vital humanitarian role played by returning soldiers.

How did families find out what happened to missing soldiers?

Families could write to the Red Cross Bureau, which followed up leads, interviewed returning soldiers, and searched military records to find out what had happened to missing men. Their detailed, honest replies were a lifeline to grieving families.

What was the Australian Wounded and Missing Inquiry Bureau?

Founded in 1915 by Vera Deakin, the Bureau investigated the fates of missing soldiers. It was staffed mostly by women and provided vital information and emotional support to thousands of Australian families during the war.

What was the German Death List?

The German Death List (GDL) was a list of soldiers killed at Fromelles whose identities were recorded by the Germans and passed back to Allied forces via the Red Cross. It remains a vital tool in identifying soldiers buried in mass graves like those at Pheasant Wood.

How did the Red Cross help identify missing soldiers after the war?

The Red Cross preserved records, witness statements, and German reports that later helped confirm the identities of soldiers. In recent years, these documents have supported DNA matching and historical research to name the unknown dead.

The Story of the Prisoners Of War captured at the Battle of Fromelles

This story has been compiled based on information sourced from the Australian War Memorial and The angel of the prison camps: Mary Chomley’ in Bruce Scates, Rebecca Wheatley and Laura James, World War One: A History in 100 stories (Melbourne, Penguin/Viking, 2015) pp. 178-183; 358.

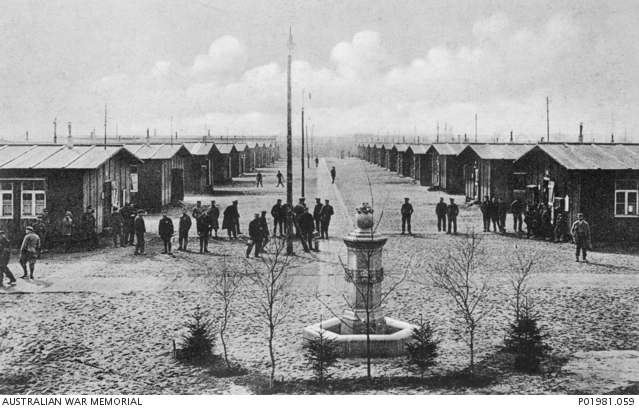

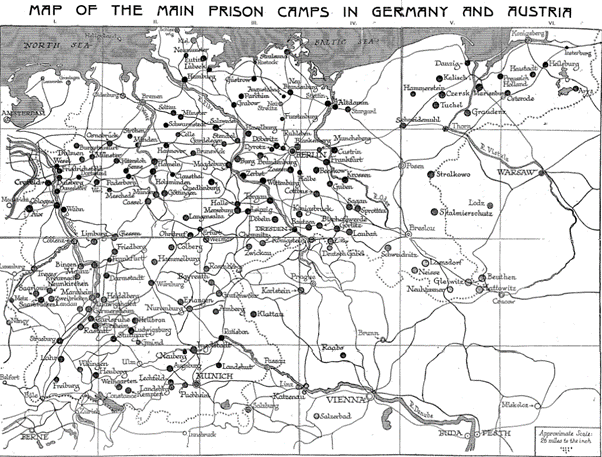

478 Australian Prisoners of War were captured during the Battle of Fromelles by the Germans, The Fromelles prisoners were gradually distributed across Germany, where they were imprisoned in camps alongside British, French and Russian troops.

Around 2000 soldiers were killed in action and approximately 3500 were wounded.

When the first Australian prisoners of war were taken by the Germans in July 1916, a separate department of the Australian Red Cross Society (ARCS) was formed to take care of them.

During the war, 3,850 Australians were captured by the Germans on the Western Front between 1916 and 1918. Nine per cent of these prisoners died in captivity. A total of 395 Australians died during captivity in the First World War.

Despite varying lengths of time behind German lines, all surviving Australian prisoners captured in France and Flanders were sent to Germany and entered an enormous prison system that comprised 105 industrial-size ‘parent’ camps (Stammlager) and over 1.6 million allied prisoners in 1916.

Source: McCarthy, The Prisoner of War in Germany, pp. 21, 53

The Australian Wounded And Missing Inquiry Bureau

Vera Deakin, founder of the Australian Wounded and Missing Inquiry Bureau in the First World War was just 23 when War broke out. Her father, Alfred, later became Prime Minister.

She was in London when the First World War began and quickly turned her energies to war work. On return to Australia, she joined the British Red Cross Society and studied nursing. She was encouraged by the Red Cross in Cairo to travel to Egypt as soon as possible. Miss Deakin enlisted the aid of Miss Winifred F. Johnson, also of Melbourne, and together they left Australia in September 1915 with no idea of what work they were to do. She arrived in Port Said on 20 October 1915 and, the following day, opened the Wounded and Missing Inquiry Bureau - an organisation devoted to finding information on behalf of the relatives of Australian soldiers then fighting at Gallipoli.

In 1916 the Bureau shifted its operations to London. The army did not view Deakin's work as favourably as might have been expected, because grieving relatives, who were unsatisfied with military explanations, came to regard the Bureau as more helpful. Peopled mainly by volunteers, the Bureau grew in size until it was dealing with up to 25,000 requests for information a year. Deakin was awarded the OBE in 1918.

Source: Australian War Memorial, https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/P156

Front Row (Left to Right): Mrs H.D.K. Macartney, Miss Webber, Miss Mary Murdoch, Miss Ruth Oliver, Miss Mary Chomley, O.B.E., (hon secretary), Mrs Mordaunt Reid (assistant hon secretary), Miss Ethel Bage, M.A., Miss D. Moore, Mrs Farrell, Mrs Maclagan.

Back Row: Miss Mabel Medlock, Miss Irene Davis, Miss Doris Weller, Miss Ralph, Miss Frances Coombe

The centre row includes: Miss Mackellar, Miss Shiell, Mrs Laher, Mrs Pegler, Miss Sursham, Miss Eilleen Chomley, Miss C.E. Wagner, Mrs Hammans, Mrs Maclaren, Mrs Bage, and Miss Cobb

The Australian Red Cross Society was a subsidiary of the British Red Cross and followed its lead in many areas. Information on prisoners of war was gathered through sister organisations in enemy and neutral countries. Enquiries about wounded and missing soldiers from their families were investigated by searchers – usually employees of the British Red Cross - who examined official lists and interviewed soldiers' comrades who might be in hospital or on active service.

Source: Australian War Memorial

For the families in the UK, Australia and around the world - the Red Cross was a lifeline to their soldier if he was a prisoner, or to tell them of the search for those listed as missing. The letters were honest, factual, and kind. The reports re the missing were as blunt as the soldier who gave the information. It was written down verbatim. The Red Cross team were collecting vital information about the missing as well as the prisoners of war.. They interviewed people in military hospitals in England and if someone mentioned another soldier who might know, they would follow all these leads, writing to their regiments and to their home addresses if they had been discharged. At the same time, they were answering letters to families who sent photos and descriptions, letters from parents, siblings fiancés, mates, friends and other relatives. Mothers, sisters, fiancés, cousins and friends were supported by the Red Cross.

The women in the soldier’s family were particularly supported, as it was in the era where the army did not relate to women. They did not communicate with them if the family had a father, sons or brothers. The army did have to deal directly with the wife or widow of a soldier, without having to go through a male family member.

A mother who wrote to the army to give their change of address received a reply asking if her husband could communicate the change of address. Even a woman who was listed as Next of Kin to the soldier was still given the same treatment. Many soldiers listed their mother as NOK, as she was obviously the family correspondent, or the father was long gone.

The first reply was always “do you have a male with whom we can correspond.”

The Australian Red Cross Prisoners of War Department

The Angel of the Prison Camps - Mary Chomley

Mary Chomley was born in 1871 at Malvern, Vic and worked for the Red Cross Society and contributed to the struggle for the equality of women both in Victoria and in England. In London during the war, she worked at the Princess Christian's Hospital for Officers from 1915-1916 and was secretary of the Prisoners of War branch of the Australian Red Cross, London, from 1916-1919. She was appointed as Officer of the Order of the British Empire (Civil) on 15 March 1918 for her contribution to the Red Cross Society.

Source: The Age, 25 July, 1960; A biographical register 1788-1939, vol. 1, p. 124.

In July 1916 the Australian Red Cross Prisoners of War Department in London was established. The initial setting up of the department was carried out by Miss Kathleen O’Connor, but as the number of prisoners of war increased, so did the workload which in turn necessitated extra staff and Mary Chomley was asked to join the organization, with the role of Superintendent / Secretary once she had grasped the details of its operation.

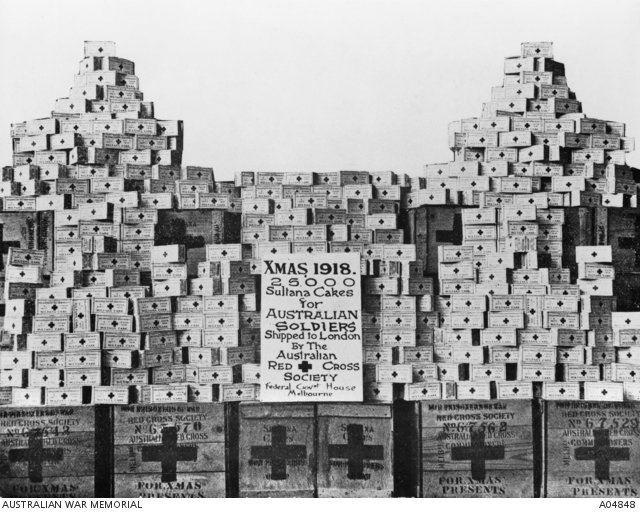

The main purpose of the department was to supply the prisoners with as many comforts as possible during their incarceration. This involved the distribution of thousands of parcels throughout the war, containing food, clothing and other necessities.

As well as overseeing the department, Mary took charge of the selection of food for the food parcels and was responsible for writing to every new prisoner of war and replying to all correspondence received from the men.

Methodical, efficient and with an insatiable appetite for work, Miss Chomley managed a team of around thirty volunteers. Most—like her—were expatriate women from Australia, many had sons, brothers or husbands serving overseas.

In more ways than one, Miss Chomley and her ‘girls’ built a lifeline to Australia. It wasn’t just that she arranged for lonely prisoners to be ‘adopted’ by Australians back home. Chomley restored men to families far away, resuming conversations cut short by captivity. Thanks to Miss Chomley correspondence between Australia and the prison camps travelled both ways across the oceans.

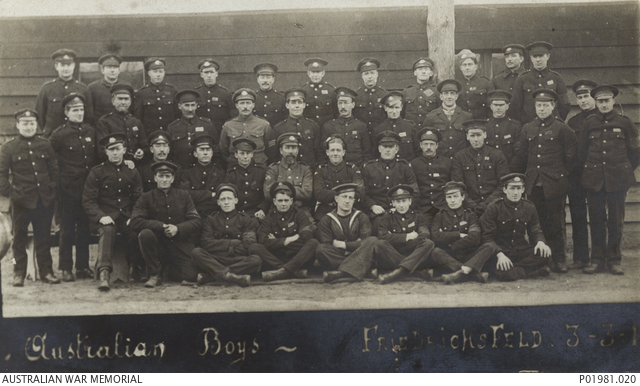

Men dubbed Miss Chomley ‘the Angel of the prison camps’. They called themselves her ‘big family of boys’ and addressed her as they would their mother. Many sent their photographs. All longed to meet her. A maternal figure she may have been, but Mary Chomley couldn’t help everyone. The British Red Cross offered relief to ‘British’ troops alone. Disowned by their government, Russian prisoners starved in their thousands.

Nor did Miss Chomley extend comfort to the enemy.

By the end of the war, the German Army fought on the verge of starvation—that was one of the reasons prisoners were treated so badly. Guards scavenged in bins for scraps from prisoners’ parcels, and blockaded by the Allied navies, the country was starved into submission. By 1919, starvation and the influenza epidemic that followed the war had claimed the lives of more civilians than men killed on the battlefield.

Not all of Miss Chomley’s ‘boys’ survived the war. Although 2,682 prisoners of war returned to Australia, around eight per cent died in captivity in Germany, most from wounds received in the fighting.

Miss Chomley herself was awarded an OBE for her war work. But not everyone was prepared to award a woman her fair share of recognition. Mary Chomley’s name was somehow omitted in Australia’s Official History of the War and management of the Red Cross Prisoner of War Department attributed to a Mr Fairburn. WHAT!

Chomley’s story reminds us of the physical and emotional labour women undertook in wartime. It shows the way war confused traditional gender roles at the same time as it reinforced them. Miss Chomley may have been called a ‘mother’ but she wore a mannish uniform. Although men described her as the ‘Angel of the Prison’, women like Miss Chomley challenged Edwardian conventions of femininity, claiming an authority and a purpose seldom seen before wartime. Chomley herself was something of a paradox, at once ardently imperialist and always proudly Australian. Finally, and perhaps most importantly, Chomley’s work offers insight into what some historians have called the forgotten soldiers of the Great War: men on all sides who languished in prison camps.

The Fromelles Prisoners

“At Fromelles, wounded men ‘found themselves’ prisoners as German troops overran their positions, while those who remained fighting were captured possessing ‘no opportunity for resistance’ ”

The Fromelles prisoners constitute the second largest group of Australians to be captured in a single engagement. In part, they were too successful in gaining ground, but without sufficient support. Having survived the devastating machine-gun fire sweeping no man’s land, groups along the 8th and 14th Brigade fronts succeeded in breaking through the German front line.

Much to the chagrin of those still willing and able to fight, the order to surrender was passed along the 14th Brigade front, and a white flag produced by an Australian officer sapped whatever morale remained. When the Germans recaptured the front line, those preparing for a final stand or attempting to withdraw were also taken prisoner.

Captain Charles Mills, was taken prisoner of war on the 20th July 1916. He was interrogated and sent to a German Prison, he and fellow officers were paraded through Lille as an example. In 1917 he was repatriated to Switzerland under an agreement suggested by the International Committee of the Red Cross and the Swiss government, Germany, France, Britain, Russia and Belgium signed an agreement in 1914 regarding prisoners of war (PoWs). The agreement stated that captured military and naval personnel who were too seriously wounded or sick to be able to continue in military service could be repatriated through Switzerland, with the assistance of the Swiss Red Cross. In 1919, He was repatriated back to England, and from then on was seconded to work with the Australian and International Red Cross to repatriate Prisoners of War, in London, then Berlin. He travelled to Germany to find missing Australian soldiers (approximately 35) remaining after the war.

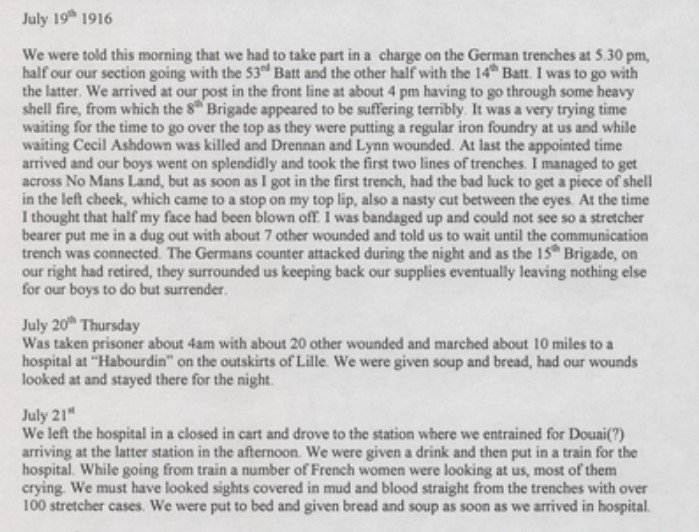

From Private Sidney McGarvey, 30 Battalion, who was captured at Fromelles:

"Those who could walk were immediately marched back to a village and placed in a barn. We were kept there till 9 o'clock that morning. Then we were marched to Lille, a distance of some five kilometres. While we were quartered in the barn it was guarded by a detachment of Uhlans. On the road to Lille we picked up an addition to our already large complement of prisoners. Some were Australians and some Warwick's were added to the procession, bringing its total number up to somewhere about 400 men. Then we marched on to Lille. There were some very badly wounded men amongst us but we were given no rest at all. "

The treatment of prisoners varied greatly, but they generally fared better the further away from the front line they were moved. After capture, officers were separated from their men, the latter being paraded through the streets of Lille and interrogated at a Napoleonic fort known colloquially as “The Black Hole of Lille”. Haking’s orders for the attack had fallen into German hands early on in the battle, so the revelation to emerge from the questioning was the degree of fighting experience and the qualities of the 5th Division.

The Fromelles prisoners were gradually distributed across Germany, where they were imprisoned in camps alongside British, French and Russian troops.

Source: Pegram, Aaron, “Australia’s Fromelles prisoners”, Wartime 44 (2008) 23