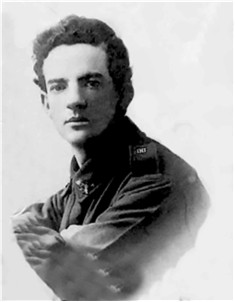

Rossiter Alfred BARRETT

Eyes blue, Hair dark, Complexion fresh

Rossiter Barrett - He Paid the Price for Devotion to Duty and His Mates

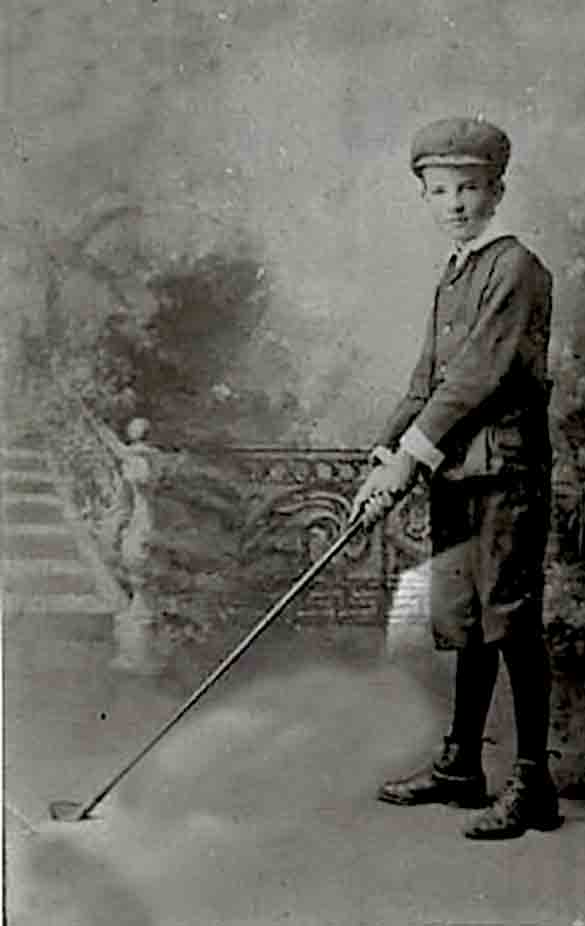

The Barrett Family of Annandale

Rossiter (Ross) Alfred Barrett was born in 1897 in Rozelle, New South Wales to George and Margaret (nee Meyer) Barrett. They raised a family of five children - Bella, Eva, Rossiter, Violet and John; and they also took in a local boy, Harold, who had been badly neglected. Harold adopted the Barrett surname, but later changed his name to Harold Somerville and moved to Newcastle. He did maintain some connection with the family.

The family lived in a few suburbs around Sydney - Rozelle, Hurstville, Marrickville - and later bought the house that is now 3 William Street in Annandale. The house was designated by the name “Rawene” and still bears the sign today.

Ross’ parents were both born in the Victorian goldfield areas around Clunes and Ballarat. George was a contract butcher like his father before him and worked locally and in Broken Hill before moving to Sydney in New South Wales. One of George’s jobs as a butcher involved him herding the cattle through the streets from the train to the butchering site in Glebe. Margaret’s parents had migrated from Germany with their parents in the 1850s.

Margaret also moved to New South Wales where she and George married in October 1894. Ross attended school in the local area. It is likely that he left school at around the age of 14, as was usual for those days. He obtained a job as an apprentice compositor/typesetter at a Sydney newspaper. It required a lot of skill to arrange the letters back to front with punctuation in the right place and to do it as some speed.

Ross joined the Cadets in Area 31 under the government’s compulsory military training scheme. As he lived in Annandale, he would have walked to the weekly training sessions in Marrickville about four kilometres away.

Off to War

In August 1915, Ross enlisted at Holsworthy in Sydney at the age of 18 years and 9 months and he was assigned to the 19th Battalion. Ross’ sister Bella’s husband, Sydney Eads (3086), also signed up around the same time and served in the same battalions as Ross. After their initial training, Ross and Sydney left Australia just before Christmas in 1915. S after arriving in Egypt, both of them were transferred to the 55th Battalion.

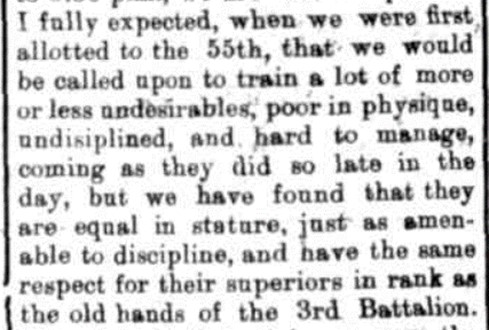

The 55th had been raised in Egypt on 12 February 1916 as part of the expansion of the AIF. Roughly half of its recruits were Gallipoli veterans from the 3rd Battalion, and the other half, fresh reinforcements predominantly from New South Wales. The new recruits seemed to fit in well with the veterans.

After six weeks of training at Tel-el-Kebir, they had a three-day march in the Egyptian heat to get to Ferry Post for further training and guarding the Suez Canal. As they marched out they were reviewed by H.R.H. the Prince of Wales.

The trip was a significant challenge, however, marching over the soft sand in the 38°C heat with each man carrying their own possessions and 120 rounds of ammunition. When they got to Ferry Post they were rewarded with a swim in the Nile.

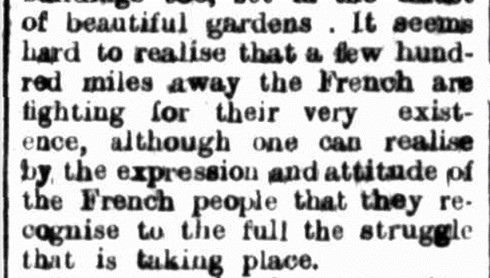

A ‘Smoking Concert’ in early June was “attended by a very vociferous but well conducted crowd of men” and on 14 June there was a Divisional Sports Contest. Source - Australian War Memorial 55th Battalion War Diary 23/72/4 June 1916 page 3 They began their move to the Western Front on 19 June, heading to Alexandria to board the HMT Caledonia. They sailed on 22 June and, after a short stop in Malta, arrived in Marseilles on the 29th. From there they were immediately onto trains for a three-day train ride to Thiennes, 30 km from Fleurbaix, and finally a chance to see what they were fighting for.

This area near Fleurbaix was known as the “Nursery Sector” – a supposedly relatively quiet area where inexperienced Allied troops could learn the harsh realities of Western Front trench warfare against the Germans. But the quiet times and the training period did not last long.

To Fromelles and Straight into Battle

Training continued, now with practicing for a gas attack added in. They marched to Estaires on the 9th and were into the trenches for the first time on 11 July. In his memoirs, Bill Boyce (3022) of the 14th Brigade 58th Battalion summed the situation up well - “What have I let myself in for?”

Source: Australian War Memorial Collection C386815

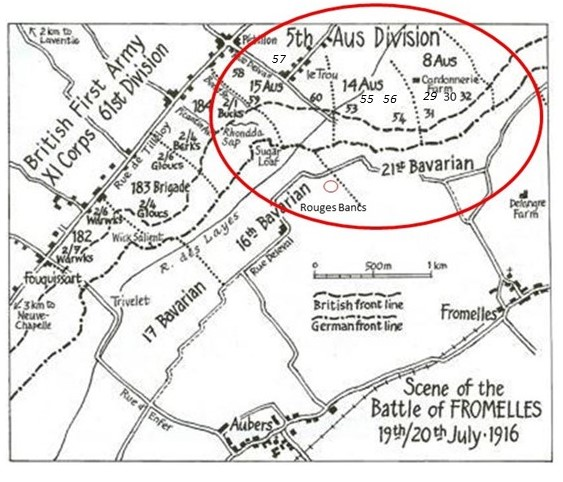

On the 16th, the 55th were carrying supplies, readying for an attack the next day, but that was postponed due to the weather.Heavy bombardment was underway from both armies by 11.00 AM on the 19th and by 4.00 PM all were in position for the battle. The main objective for the 14th Brigade was to take the trenches to the left of a heavily armed, elevated German defensive position, the ‘Sugar Loaf’, which dominated the front lines. If the Sugar Loaf could not be taken, the Australians would be subjected to murderous enfiled fire from the machine guns and counterattacks from that direction. As they advanced, they were to link up with the 31st and 60th Battalions.

The 55th’s role was to provide support for the attacking 53rd and 54th Battalions by digging trenches and providing carrying parties for supplies and ammunition and carrying messages. They would be called in as the ‘third battalion’ if needed for the fighting.On 19 July, Zero Hour for advancing from their front-line trenches was to be 5.45 PM, but the Germans knew this attack was coming and were well-prepared. They opened a massive artillery bombardment on the Australians at 5.15 PM, causing chaos and many casualties. As the battle began, C & D Companies’ carrying parties were in position 300 yards from the front line and A & B Companies were ready to move forward after the first waves of the 53rd and 54th had gone forward.

The 53rd and 54th went on the offensive from 5.43 PM. They did not immediately charge the German lines, but went out into No-Man’s-Land and laid down, waiting for the British bombardment to lift. At 6.00 PM the German lines were rushed with Ross’ C Company & D Company following in support. There was heavy artillery, machine gun and rifle fire, but they were able to advance rapidly. At 7.24 PM the remainder of the 55th battalion moved to the front lines, but were ordered to not leave their front line. Not long after however, help was needed and at 8.55 PM A Company was into the fighting to support the 53rd and B Company to support the 54th.

They were able to do move forward with few casualties. The 53rd and 54th were able to link up with the 31st and 32nd, occupying a line from Rouges Bancs to near Delangre Farm. By 10.00 PM all of the 55th were past the front line. As they advanced, they found that their right flank was not protected by the 15th Brigade, who had not been able to progress due to the devastating defences at the Sugar Loaf. The 55th tried to shore up their flank defences, but:

“The Huns knew the country and trenches so perfectly that they succeeded time and again in bombing us back.”

A bayonet charge was made by about 50 men and they were able to advance about 60 yards.By 1.00 AM things had quietened down, but only for a short time. About 3.00 AM some ‘foolish orders’ were circulated that they were being bombed by their own side and were supposed to retreat. These were believed to be incorrect and they fought on.

At 4.15 AM about 50 men of the 55th were ordered back to their own front line to defend against a rearguard action as the Germans were coming in from the exposed right flank.

“It was due to the very fine actions of these men that the garrison was able to get across No Man’s Land with comparatively few casualties.”

Source: AWM4 23/14/4, 14th Brigade War Diaries July 1916 page 106

By 9.30 AM the Brigade had ‘retired with very heavy loss’.

Source - AWM4 23/14/4 14th Brigade July 1916 page 7

The artillery finally ceased at noon.The Commanding Officer of the 55th, Lieutenant Colonel D. M. McConaghy spoke proudly of his men:

“The losses were heavy, but the battalion, four-fifths or more of whom were strangers to battle, acquitted themselves honorably in its first engagement, and returned with 40 German prisoners.”

For a battalion that was to be in reserve as the ‘third battalion’, the initial count at roll call was 42 killed or died of wounds, 154 wounded and 143 missing. Ultimately the impact was that 84 soldiers were killed or died from wounds. Of this total, 46 were unidentified, including Ross.

Ross’ Fate

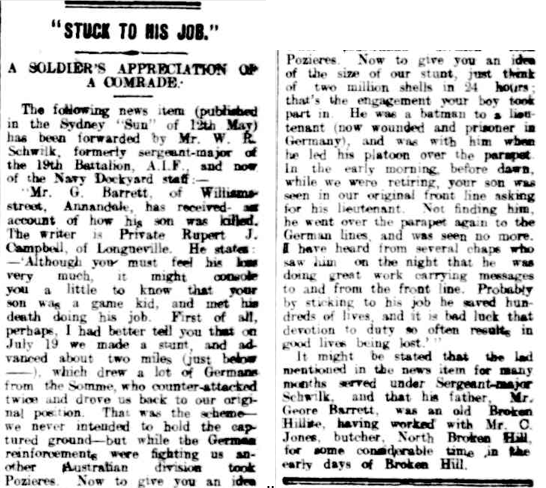

While the AIF and Red Cross records had little detailed information about Ross, his mate Rupert J. Campbell (3297) wrote a letter to Ross’s family describing Ross’ role in the battle and praising his devotion to duty and his mates:

“I have heard from several chaps who saw him during the night that he was doing great work carrying messages to and from the front line. Probably by sticking to his job he saved hundreds of lives, and it is bad luck that devotion to duty so often results in good lives being lost.”

“While we were retiring your son was seen in our original front line asking for his lieutenant. Not finding him, he went over the parapet again to the German lines and was seen no more.”

His mother’s long search for Ross

Ross’s father George, as nominated next of kin, was advised in mid-August 1916 that his son was missing in action – and so began a series of letters from Ross’s mother that spanned from 1916 to 1923 to find out what happened to him. She always believed that he had been taken as a prisoner of war and had been buried in Germany. The family’s anguish at the time was compounded as Ross’s sister, Bella, also received notification that her husband, Sydney Eads, was missing in action. However, in October, Bella received better news - Sydney had survived and was a prisoner of war, where he remained until the end of the war.

What information was available to be provided to families was sparse and often came from several sources. Given all the deaths, POWs and clerical requirements in clearing reporting channels in both Germany and England, it is not surprising that delays in accurate information would occur. Thus, a clear picture about exactly what happened to Ross may not have been known by his family for a long time, other than he had not survived.

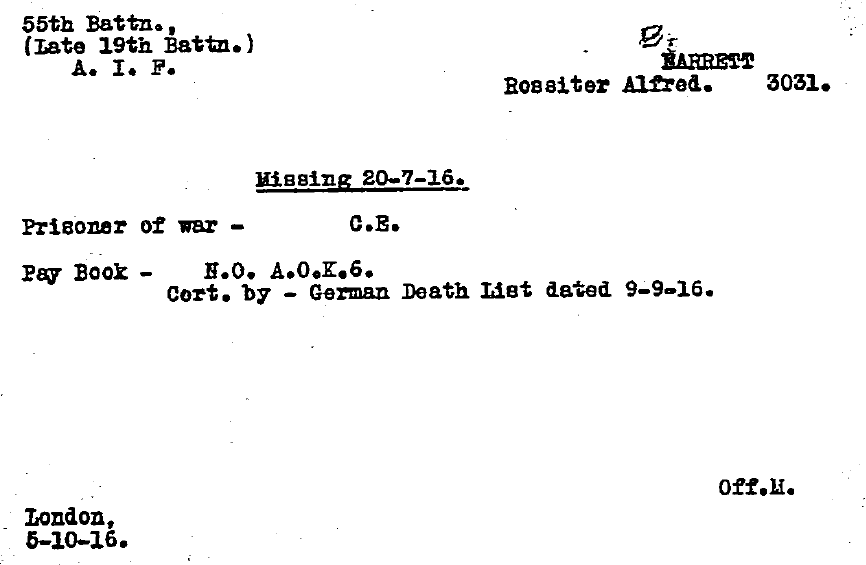

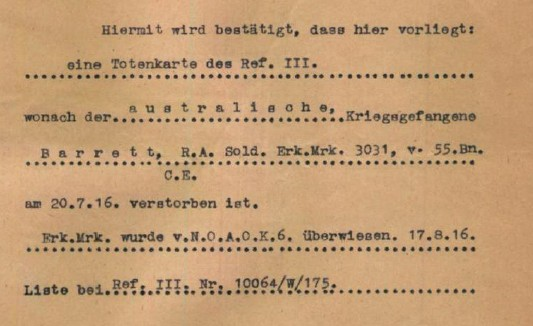

In October there is a Red Cross report, presumably provided to the family, that had shown Ross as a prisoner of war, but it also that he was on a 9 September German ‘Death List’. His ID tag the Germans had recovered was returned to the family in May 1917.

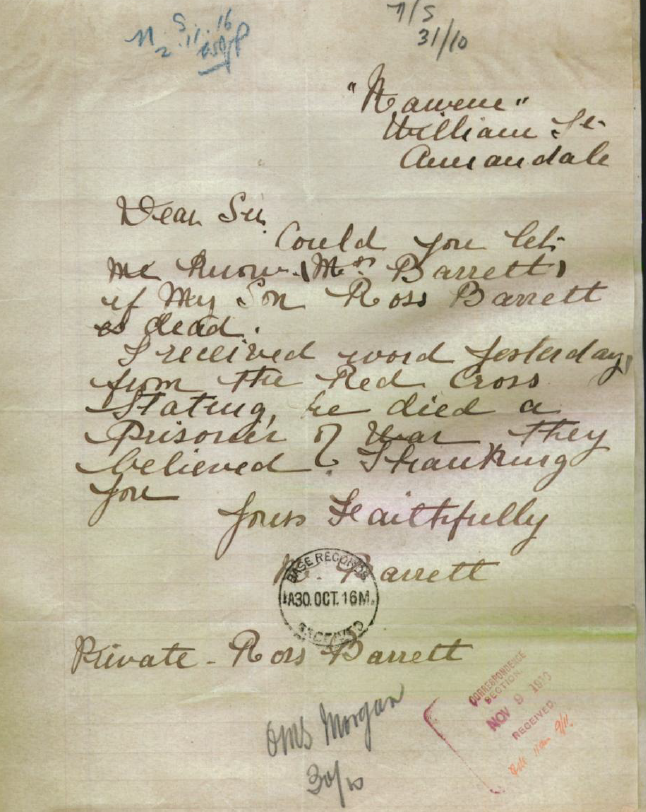

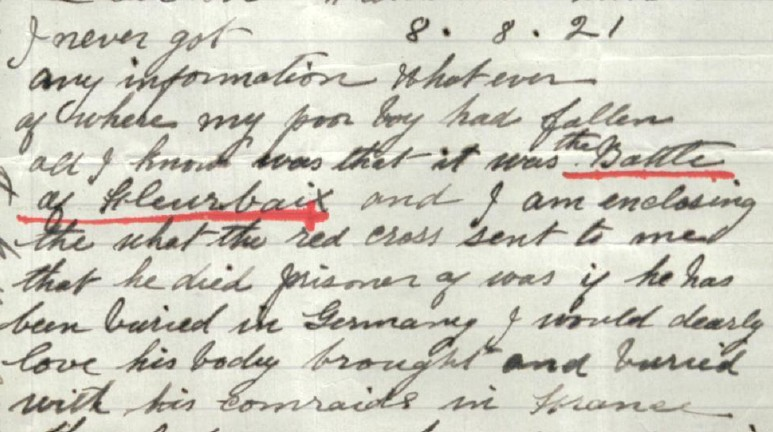

This prompted his mother, Margaret, to seek more information. From her letter, below, it seems likely that she interpreted the report to mean that Ross had lived as a POW until September, but then had died, which would have meant that Ross should have had a grave in Germany.

There is also a November 1916 Red Cross report about Ross’ death that states (cautiously), “We cannot say that this is final because in some cases it has happened that a man who has been on this evidence reported to have died as prisoner and afterwards been found in a prison camp”

Source - Australian Red Cross Wounded and Missing Files – Rossiter Alfred Barrett p 5

What she may not have been provided with are the definitive reports from the Germans, that stated he had died on 20 July, not in September. The November 1916 AIF Enquiry in Field about Ross’ death had confirmed this date.

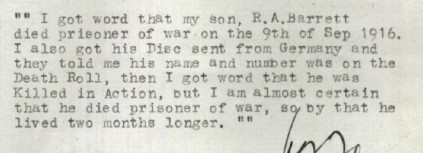

Margaret’s belief that Ross had died as a POW in September 1916 did persist, as this was repeated in a 1919 telex and again in a 1921 letter.

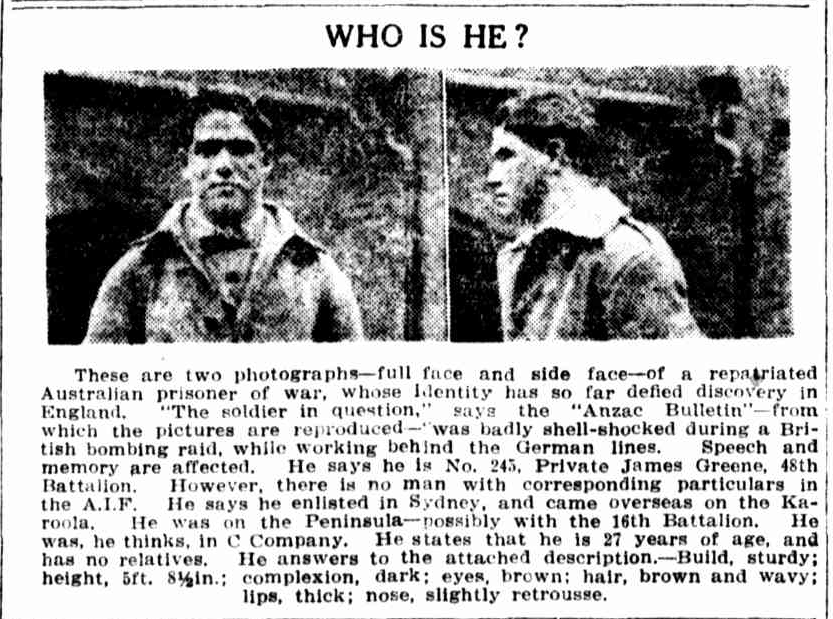

While his death had been confirmed, if not his burial site, still hopeful even after many years, Margaret came across a 1919 news article of a young former POW who was badly shell-shocked and whose description was “very much like my boy”.

Military authorities kindly advised that the man had been identified and was not her son and that there was no reason to doubt the reports that her son had been killed in action.

The ‘final word’ for Margaret…from Germany

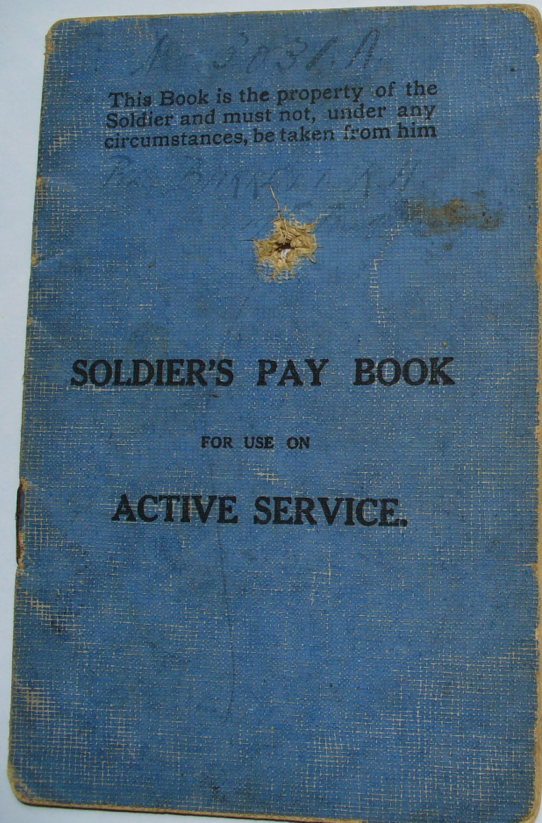

The final word for Margaret came in 1923 from a VERY unusual source…a German soldier who had found (and kept) Ross’s pay book. In August 1923 the Barretts received a letter from a German soldier, Martin Geyer. The letter gave details about how Rossiter died - shot through the heart - and he had also enclosed Ross’ pay book – with the bullet hole - as proof. He also stated that he had helped to bury Ross. Family members have provided the following transcription of the letter:

“Bavaria 8th August 1923

Dear Sir,

Hoping you will pardon me for writing this few lines to you and forwarding the Paybook of your son Rossiter Alfred Barrett.

His company fought against us in France on 18th of July 1916 and took two of our positions at Fromelles. On the 19th of July we took our lost positions back again and in that fight your son lost his life, like many more of his fellow soldiers. He had a shot through the heart, as his book will show you and must have been dead instantly. He had nothing on him but his Paybook, which I thought I keep as a keepsake of this terrible War.

We buried your son on the 22nd of July at Boukham, near Fromelles in France with many of his Comrades.

A few days ago I showed his book to a friend of mine as we were talking about the War and he advised me to send it back to you right away. He speaks English well and he was kind enough to write this letter for me. I enclose the book hoping you will receive it alright. Perhaps you be kind enough to drop me a line if you got it.

With the best wishes I remain Yours truly, Martin Geyer”

(Note - Boukham is likely referring to Beaucamps-Ligny, 5 km from the Pheasant Wood site, a German cemetery and some soldiers of the battle were buried there. Martin’s 1923 statement isn’t a ‘lie’, it’s more likely he probably didn’t know the name of where the Pheasant Wood grave site was and he just wanted to help a family in their mourning.)

Based on this, Margaret again asked for a photo of the grave, but there was none to be had. Ninety-four years after his death, Ross was identified as being in the Pheasant Wood grave. We now know that Ross HAD been buried by the Germans, but at the vicinity of the battle site in France. After all this time, closure for the family, but far too late for Margaret.

Remembering Ross

Over the decades, the extended Barrett family have kept the memory of Ross alive. In the immediate aftermath of his death, his younger sister, Eva Pinson (nee Barrett), named her second son born in 1917 Rossiter Barrett Pinson in her brother’s honour. Rossiter’s sister Violet also named her second son born in 1929 Ross Phillip Mair. His nephew, Doug Barrett, also called his son Ross Barrett in honour of Rossiter.

His name is also honoured on the Annandale First World War Memorial in Annandale Park. It was here that his nephew, Doug Barrett, paid tribute over the years to his uncle’s sacrifice. In a 2016 news article relating to the centenary of the Battle of Fromelles and of Ross’s death, Doug is quoted as saying that he will remember his uncle in a special local way :

“As usual I will go down to the War Memorial in Johnson Street, Annandale where Rossiter’s name is listed next Tuesday, July 19, 2016 and lay flowers.”

Further, when the opportunity arose to assist in possibly identifying Ross, many family members, all descendants of Ross’ siblings, were keen to offer assistance and DNA samples. In 2010, Margaret Barrett’s dream of her son’s burial place being found and honoured was finally realised when DNA identification was successful. His burial place in the Pheasant Wood Cemetery at Fromelles was rededicated with a headstone inscribed with her son’s name at last. A number of family members have since made the journey from Australia to France to pay tribute to nineteen-year-old Private Ross Barrett.

Right - Great-niece Peta Gogan at Ross’ grave, 2014

Family member, Peta Gogan, commented on her visit to Fromelles:

“There was one poppy flowering in the field the day we went there. It was a sign, I think, Rossiter knew we were there to see where he had been since 1916. It still makes me feel emotional when I see this photo.”

His grave at Pheasant Wood reads:

Rossiter, never forgotten, Beloved son of Margaret& George, Brother of Bella, Violet, Eva and John, RIP

Links to Official Records

The Fromelles Association would love to hear from you

Contacts

(Contact: carla@fromelles.info or geoffrey@fromelles.info).

(Contact: army.uwc@defence.gov.au or phone 1800 019 090).

Donations

If you are able, please contribute to the upkeep of this resource.

(Contact: bill@fromelles.info ).