George’s headstone at Pheasant Wood taken 2024

George Henry LUCRE

Eyes blue, Hair brown, Complexion fair

George Henry Lucre - “A true staunch mate…he stood by his comrades till he dropped”

Early Life

George Henry Lucre was born on 11 May 1893 in Sydney, New South Wales, to Joseph James Lucre (1871-1939) and Ellen Maud Gunn (1873-1917) . The Lucre family were orignally from Wiltshire in England.

George had three sisters:

- Grace Lillian (1895–1932)

- Eileen (1898–1950)

- and Ellen Alice (1900–1950)

George grew up in Cook’s Hill, Newcastle, with his siblings in a close-knit Roman Catholic family. His father was born in Orange NSW, to Henry and Elizabeth Lucre, who later moved to Bathurst and then Sydney where father worked as a wharf labourer. George attended school locally. He spent 18 months serving in the Senior Cadets, gaining foundational military training before enlistment.

At 17 he joined the NSW Government Railways as a shop boy n 4 July 1910 and by 1914 he had progressed to become a railway permanent way driller and machinist. Outside of work, George was a keen footballer, playing for the South Newcastle Rugby League Club.

He was among seventy-eight players from the club who enlisted during the war, including Garnet Dart, Edward Malcolm, Alfred Smith, Walter Smith, and Eric Arkell and Max Arkell – several of whom were killed at Fromelles alongside him.

Off to War

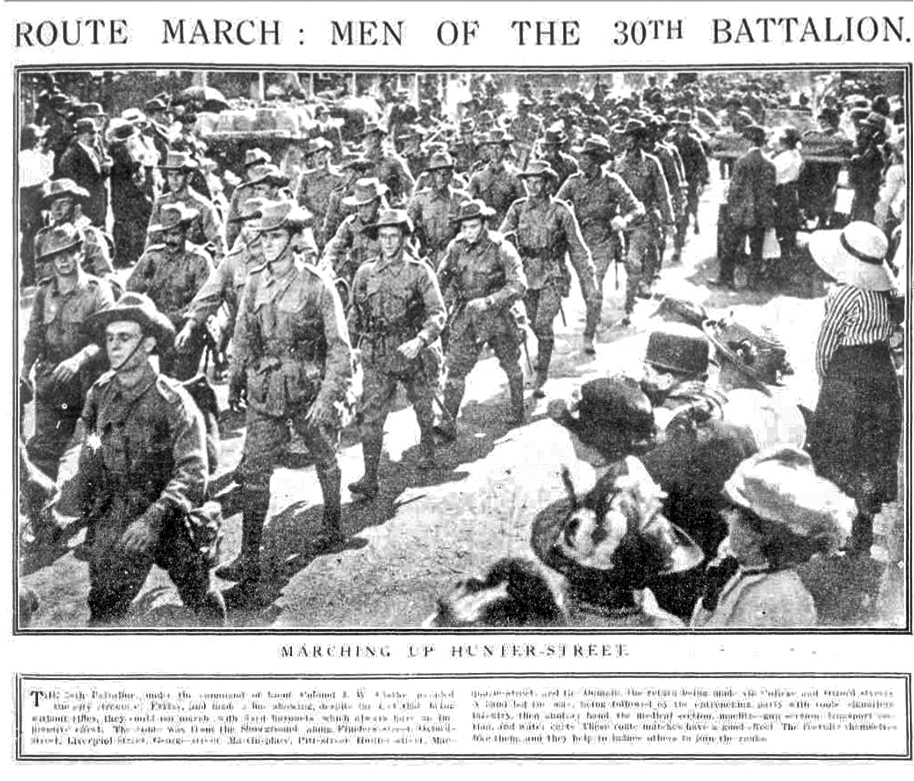

With war fever high across New South Wales, George enlisted on 21 July 1915 at Liverpool, aged 22. He was assigned to the newly formed 30th Battalion, B Company, and commenced training at Liverpool Camp. In September 1915, the 30th Battalion moved to the Royal Agricultural Showgrounds at Moore Park, Sydney, for final training and preparation before embarkation. During this time, they undertook route marches through the city, drawing crowds who cheered them on and showered them with chocolates and cigarettes.

By early November 1915, their training had turned them into soldiers, ready for deployment. Many country boys in the battalion had never seen big ships or aeroplanes before, and embarking was the start of an enormous and daunting adventure. On 9 November 1915, the 30th Battalion marched from Sydney Showgrounds to board HMAT A72 Beltana. The crowds farewelling them were immense, Union Jack flags waving, bands playing, and emotional families and sweethearts lining the streets and wharves. As the Beltana pulled away from the docks, the traditional streamers broke and drifted into the harbour, launches and ferries following them out through Sydney Heads with horns sounding in farewell.

It wasn’t just George who enlisted from the family, his 44 year old father, Joseph, followed his example and enlisted in November 1915. Joseph was allocated to the 35th Battalion and was headed for Europe in May 1916. George’s trip was uneventful and he disembarked in Egypt on 11 December. His first seven weeks in Egypt were spent at Ferry Post guarding the Suez Canal from any potential threats posed by the Ottoman Army and continuing their training. February and March were spent at the 40,000 man camp at Tel-el-Kebir, 110 km northeast of Cairo. While there, they were inspected by H.R.H. Prince of Wales.

For much of April and May were back in Ferry Post, including some time in the front-line trenches there. There were the usual complaints of the heat, water supplies and flies. The Battalion left Egypt for the Western Front on 16 June 1916 on HMAT Hororata and arrived in Marseilles on 23 June. After landing, they were immediately entrained for a 60+ hour train ride to Hazebrouck, 30 km from Fleurbaix. They arrived on 29 June and then encamped in Morbecque.

Private F.R. Sharp (2134) wrote home:

“From the time we left Marseilles until we reached our destination was nothing but one long stretch of farms and the scenery was magnificent.” “France is a country worth fighting for.”

The area near Fleurbaix was known as the “Nursery Sector” – a supposedly relatively quiet area where inexperienced Allied troops could learn the harsh realities of Western Front trench warfare against the Germans. But the quiet times and the training period did not last long. Training now included the use of gas masks and they also would have heard the heavy artillery from the front lines.

The Battle of Fromelles

On 8 July they were headed to the front lines, first to Estaires, 20 km and the next day 11 km to Erquinghem, where they were billeted at Jesus Farm. They got their first ‘taste’ of being in the front lines at 9.00 PM on 10 July. A week later, they got orders for an attack, but it was postponed due to the weather.

In his final letter home Charles Albert Woods (2194 30th Bn) summed up the situation he found himself in:

“Since writing last we have shifted from ‘somewhere in France’ to ‘somewhere else in France,’ and are now in the trenches. Whilst writing this the shells are whistling over our heads a ‘treat.’ We are all provided with steel helmets to lessen the danger of being hit in the head with shrapnel, and also with gas helmets, to put on while a gas attack is being made on us.”

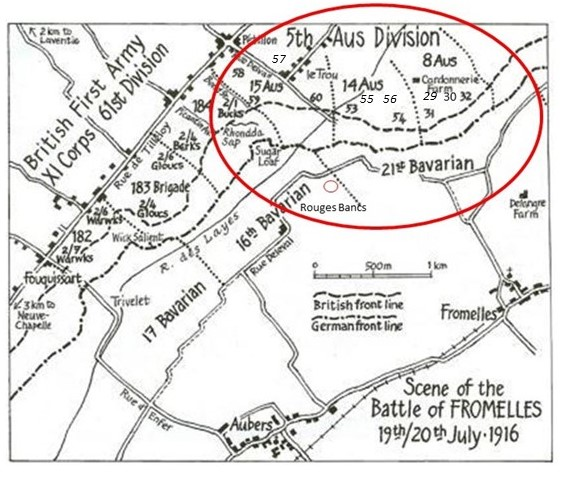

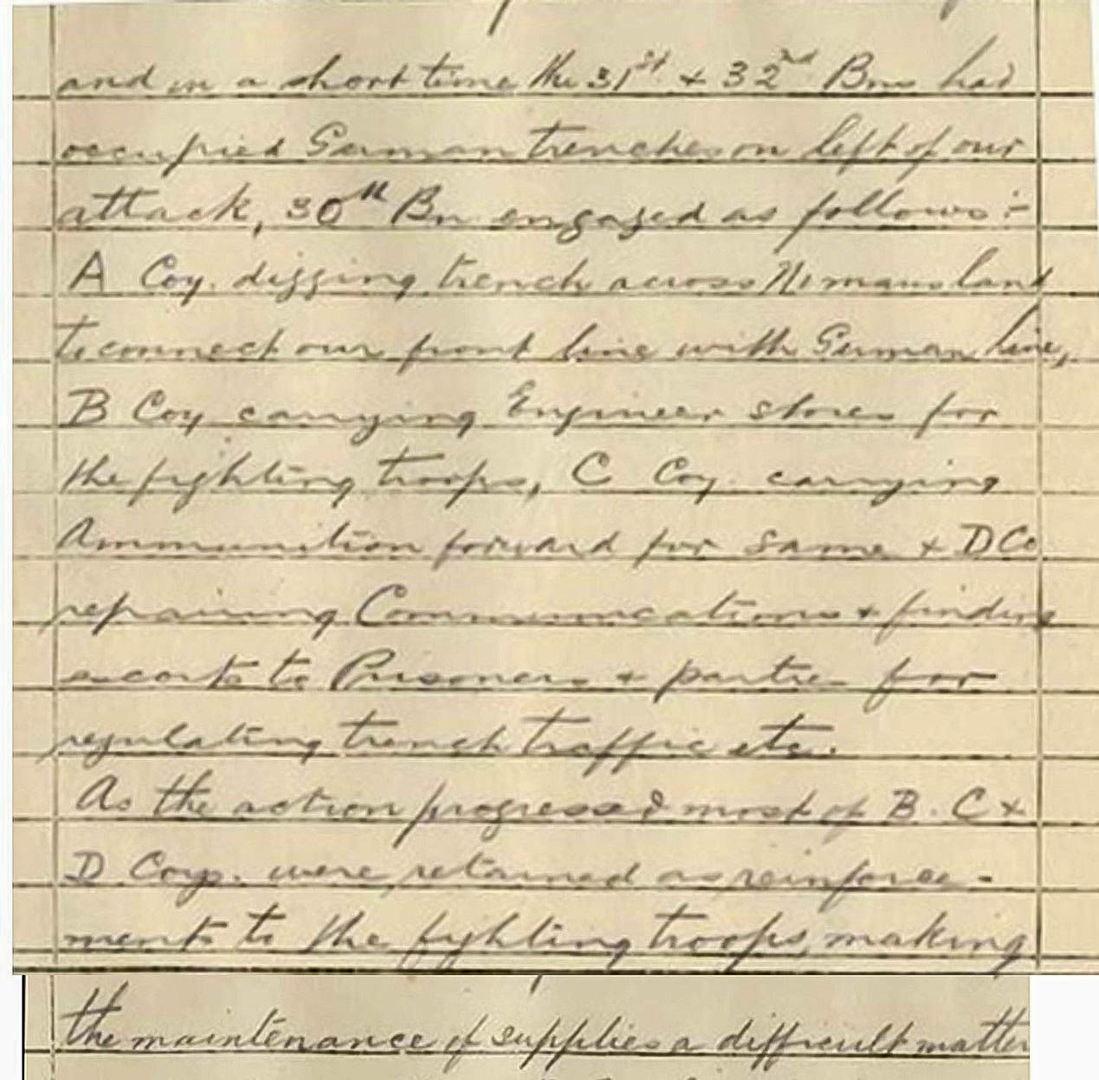

Then, on 19 July, the 29 officers and 927 other ranks of the 30th Battalion were into battle. The overall plan was to use brigades from the Australian Fifth Division to conduct a diversionary assault on the German trenches at Fromelles. The 30th Battalion’s role was to provide support for the attacking 31st and 32nd Battalions by digging trenches and providing carrying parties for supplies and ammunition. They would be called in as reserves if needed for the fighting.

On 19 July, Zero Hour for advancing from their front-line trenches was to be 5.45 PM, but the Germans knew this attack was coming and were well-prepared. They opened a massive artillery bombardment on the Australians at 5.15 PM, causing chaos and many casualties. The 32nd’s charge over the parapet began at 5.53 PM and the 31st’s at 5.58 PM. There were machine gun emplacements to their left and directly ahead at Delrangre Farm and there was heavy artillery fire in No-Man’s-Land.

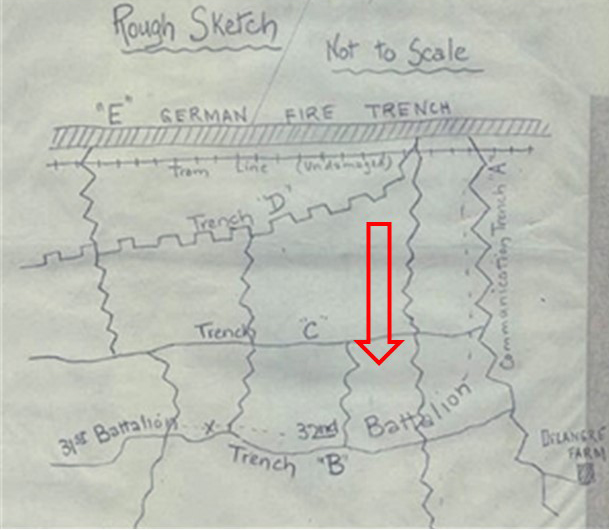

The initial assaults were successful and by 6.30 PM the Aussies were in control of the German’s 1st line system (Trench B in the diagram below), which was described as “practically a ditch with from 1 to 2 feet of mud and slush at the bottom”.

Source: AWM4 23/49/12, 32nd Battalion War Diaries, July 1916, page 11

George was assigned to these carrying parties to support these advances. Throughout the evening and into the night, he and his comrades repeatedly crossed No Man’s Land under machine-gun, rifle, and artillery fire. His mates describe the danger of these tasks:

“The Germans’ first and second lines of trenches had been taken and George was one of the great number who had been given the job to supply ammunition to the new position. This meant running across No Man's Land, a distance of about 200 yards, under very heavy shell and shrapnel fire, also the ground had been ploughed up by our own artillery, and barbed wire was strewn all over the place.

This venture was almost certain death, but he did it like a soldier, and accomplished three or four journeys of this hazardous task, when he was then held in the first line to reinforce the position. He carried on during the night of the 19th and on into the early hours of the 20th, doing his work in a cool and collected way.”

While the 30th’s role was to be in support, commanders on scene also made the decision to use the 30th as much-needed fighting reinforcements. A necessary act, but it had consequences as it interfered with the planned flow of supplies.

By 8.30 PM the Australians’ left flank had come under heavy bombardment with high explosives and shrapnel. Return bombardment support was provided and they were told that “the trenches were to be held at all costs”.

Source: AWM4 23/49/12, 32nd Battalion War Diaries, July 1916, page 12

When the 30th was formally called to provide fighting support at 10.10 pm, Lieutenant-Colonel Clark of the 30th reported:

“All my men who have gone forward with ammunition have not returned. I have not even one section left.”

Fighting continued through the night. The Australians made a further charge at the main German line beyond Trench B, but they were low on grenades, there was machine-gun fire from behind from the emplacement at Delangre Farm and they were so far advanced that they were getting shelled by both sides. At 4.00 AM the Germans began an attack from the Australian’s left flank, bombing and advancing into Trench A (map).

Given the Australian advances that had been made earlier, portions of the rear Trench E had been left almost empty, which then enabled the Germans to be in a position to surround the soldiers. At 5.30 AM the Germans attacked from both flanks in force and with bombing parties. Having only a few grenades left, the only resistance the 31st could offer was with rifles:

“The enemy swarmed in and the retirement across No Mans’ Land resembled shambles, the enemy artillery and machine guns doing deadly damage.”

By 10.00 AM on the 20th, the Germans had repelled the Australian attack and the 30th Battalion were pulled out of the trenches. The nature of this battle was summed up by Private Jim Cleworth (784) from the 29th:

"The novelty of being a soldier wore off in about five seconds, it was like a bloody butcher's shop."

Initial figures of the impact of the battle on the 30th were 54 killed, 230 wounded and 68 missing. To get some perspective of the battle, when Charles Bean, Australia’s official war historian, attended the battlefield two and half years later, he observed a large quantity of bones, torn uniforms and Australian kit still on the battlefield. The ultimate total was that 125 soldiers of the 30th Battalion were either killed or died from wounds and of this total 80 were missing/unidentified.

George’s Fate

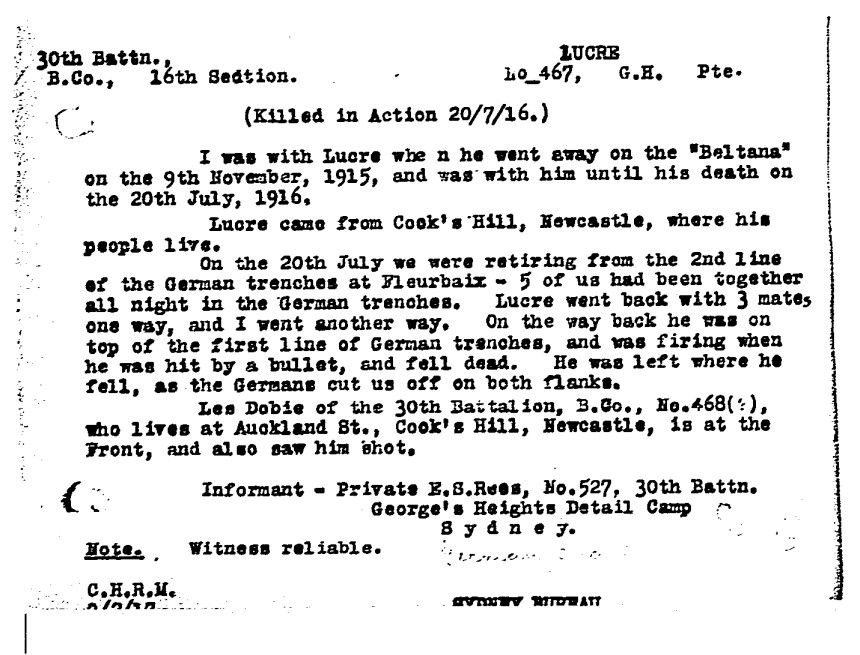

George had somehow survived supporting the advances, but was killed during the retreat while firing his rifle from the German parapet, holding his ground as his comrades withdrew. Edris Rees (527, 30th Battalion) was one of a number of George’s mates to give a detailed statement of George’s fate and that they had to leave him where he fell.

Several other of his mates confirmed this and William Sutherland (334) also added:

“He did very fine work that day. He was with the carrying party, carrying ammunition bags and bundles across to put up a good fight.”

And another from William H. Webb (568):

“He was killed instantly. We had to retreat in a counter-attack by the Germans and consequently we were unable to bury him.”

A letter that as sent in early October to his mother, Ellen, from his Lieutenant and members of his Company officers later confirmed Geroge’s role in the battle and the mateship that he had developed:

“He was one of my best men, always willing to do anything required of him. He was most popular amongst his mates. A splendid soldier and a thorough gentleman.”`

His mates went on to add:

“At about 3 a.m., on account of superiority of numbers and their precarious position the line had to retire. This was done in an orderly manner, and the men came back to the Germans’ first line.

Here a stubborn fight was put up and it was in this trench that George met his death while trying his utmost to hold the enemy back by his rifle fire, and also throwing bombs.

He was killed instantly and suffered no pain, as the bullet passed through his head.”

They closed with heartfelt words:

“Although he did not speak, yet his last thoughts were of his dear parents and sisters, as we know through being with him for twelve months, his first thought always was to cause you no worry at all, and to make his absence lighter for you to bear. At all times he was always willing to do more than his share, and he did it without a murmur.

In him we have lost a true staunch mate who was loved by all he came in contact with and who stood by his comrages till he dropped.”

“But you, madam have lost a greater treasure in losing such a loving son, who was killed while performing his duty and helping to save britain from being ruleld by Germany.

(Signed) M. Baxter, W. J. Coleman, A. A. Bell, E. S. Rees, L. F. Dobie, E.W. Hunt, R. Dunn, O. R. Bradley, S. R. McDonald, A. Pardey.”

George was among many young men from Cook’s Hill and Newcastle who never returned from Fromelles, his bravery and sacrifice remembered by mates who described him simply as “a splendid soldier and a thorough gentleman.”

After the Battle

Given the scale of the battle, news about what happened to George would have been slow in coming in as the Army they scrambled to assemble all the information. As decribed above, Ellen did receive detailed information about what happened to her son from the October 1916 letter his Lieutenant and his mates had sent. Georges’ father Joseph, who was with the 35th Battalion, had arrived in England from Australia on 9 July 1916, just eleven days before George was killed. He may not have learned of his son’s death for some time.

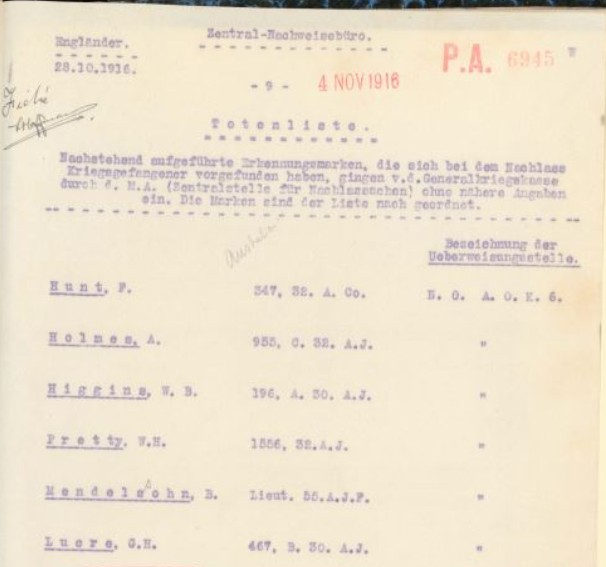

George was formally declared as killed in action on 20 July 1916 in an Enquiry in the Field held on 13 September 1916. A further confirmation of his death came later, as his identity disc was recovered by German forces and his name appeared on the German Death List (Totemliste) dated 4 November 1916. This official German record listed soldiers whose bodies had been found behind their lines. His identity disc was returned via the Red Cross and despatched to his family in June 1917.

Joseph spent the winter of 1917 with the 35th in the field. While it was a harsh winter, It was mostly quiet until they took part in the fighting around Messines in June. However, between his age and the weather, in July he ended him up in hospital with a diagnosis of reumatism due to age. He remained in ‘Base Duties’ until his discharge in December 1917 and returned to Australia.

Just a year after George’s death, the family were struck again – George’s mother/Joseph’s wife Ellen died on 8 June 1917. Joseph was unable to be with his wife in her final days or to attend her funeral in Newcastle. She was laid to rest at Sandgate Cemetery. George’s family and community remembered him with deep love and pride. His sisters and brother-in-law published this tribute in July 1917:

LUCRE. – In loving memory of our dear brother, Private G. H. Lucre, killed in action in France July 20, 1916.Greater love hath no man than he who lay down his life for his country.Inserted by his loving sister and brother-in-law, Grace and William Robinson, and sister Eileen.

The following year, Joseph honoured his son’s sacrifice:

LUCRE. – A tribute of love to the memory of my dear son, Private George H. Lucre, killed in action at Fleurbaix, Pozieres, France, July 19, 1916; aged 23 years. – His duty done.Inserted by his loving father, J. Lucre, Cook's Hill (late of A.I.F.).

In early 1917, George’s rugby mate Private Garnet Dart wrote from Glasgow reflecting on the news from home and the toll the war had taken on his old friends:

“I wrote a long letter to poor Teddie Malcolm, and was greatly surprised to receive a letter from old ‘Daddy’ Wilson in reply to it. Therein he stated that ‘Teddie’ was missing, that poor Alfie Smith, (George) Lucre and Eric Arkell had gone on the long journey.It is hard to think that they are no more. I liked them both much. With Alf I went to the good old Cook’s Hill School, and Teddie I associated with in the surfing world. Poor Ted! He did much during his term as hon. secretary of the old surf club (Cook's Hill) to further it on the ladder of success.”

He is also remembered among the fallen of the South Newcastle Rugby League Club:

“Seventy-eight players who had played or had a permit to play with the South Newcastle Club have enlisted. Eight of them have fallen, viz., George Lucre, C. H. Hawcroft, Dave Hay, E. Blanche, A. Smith, W. Wolston, F. Poole and J. Larkins.”

George was awarded the 1914-1915 British War Medal, the British War Medal, the Victory medal and a Memorial Plaque.

He is commemorated at:

- VC Corner (Panel no 2), Fromelles, France

- Australian War Memorial Roll of Honour, Panel 117

- Haymarket NSW Government Railway and Tramway Honour Board, recognising his service as a railway machinist

Finding George

For decades, George was commemorated on the V.C. Corner Australian Cemetery Memorial at Fromelles as having no known grave. Then, in 2009, a mass grave near Pheasant Wood was discovered and excavated. Through detailed DNA analysis from family members and research by the Australian Army’s Unrecovered War Casualties team and their international partners, George was formally identified in 2010.

George also had an uncle, George Henry Lucre (Service No. 5700), who shared his name. Born in Balmain in 1887, his uncle enlisted in 1916 and served with the 3rd and later 53rd Battalion. He returned to Australia in April 1918 and lived until 1939. This duplication of names often led to confusion in records and family memory, but both men served their country with courage.

Hedy Lucre-Impens, a relative of George’s, recalls that her grandmother had compiled the family history, but like many families, speaking about the war wasn’t part of growing up. “We haven’t found a photo yet, but will keep searching.” Her children’s father, Frederick, came from nearby Ghent in Belgium — a country at the northern end of the Western Front, where Australian troops also fought later in the war. Fromelles, though in northern France, lay only a short distance south of the Belgian border, in the same devastated war zone:

“For almost a century we did not know where George lay. Now, he rests with his mates, his name spoken with love, his sacrifice never forgotten. My hope is that my children will grow up knowing his story, and understand the legacy of courage and sacrifice he left for them.”

He now lies at rest in an individual grave at the Fromelles (Pheasant Wood) Military Cemetery, Plot III, Row D, Grave No. 7. His headstone inscription reads:

“ONCE LOST NOW FOUND FOREVER REMEMBERED NOW WITH GOD”

Links to Official Records

The Fromelles Association would love to hear from you

Contacts

(Contact: carla@fromelles.info or geoffrey@fromelles.info).

(Contact: army.uwc@defence.gov.au or phone 1800 019 090).

Donations

If you are able, please contribute to the upkeep of this resource.

(Contact: bill@fromelles.info ).